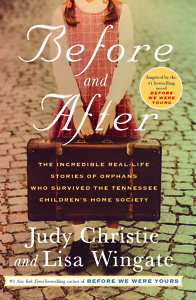

The Truth Shall Set You Free

Victims of an infamous Memphis adoption mill tell their stories in Before and After

The horrors of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society — Georgia Tann’s adoption mill that flourished in Memphis from 1924 until Tann’s death in 1950 — are now well known. Less familiar, but equally heartbreaking, are the long searches many of those adoptees have made for their birth families. Co-authors Lisa Wingate and Judy Christie have collected some of those stories in Before and After.

After reading Wingate’s 2017 novel based on Tann’s activities, Before We Were Yours, Connie Wilson, one of the TCHS adoptees, emailed the author with a stunning idea: “Have you considered a reunion?” Intrigued, Wingate pulled her friend and fellow author Christie into the project, and the three women began searching for Wilson’s fellow adoptees. “Piecing together stories of siblings who struggled for decades to find one another brings to my mind those movies where the hero absolutely, positively refuses to give up,” Christie writes.

Protected by Memphis politicians and judges, Tann ruthlessly swept up choice babies from the docks, streets, and backwoods of Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi. TCHS sent more than 5,000 children to eager would-be parents from coast to coast, many of whom were too old or otherwise ineligible to adopt children through traditional routes. Another 500 children are believed to have died of neglect and abuse in Tann’s custody.

Tann delivered these desirable white, preferably blond, babies and toddlers for prices estimated as high as $14,000 in today’s dollars. Satisfaction was guaranteed, with the right of return, as Edmund Smiley Burnette, one of four children adopted by Hollywood cowboy Smiley Burnette, tells Christie: “One time when she came, she had delivered a couple of kids to neighbors on the same street. Some people up the block got a good one. They adopted a second one who didn’t work out and sent him back.”

The stories in Before and After reveal how the operation’s tentacles stretched across the South, into local clinics and food kitchens. The child of an adoptee describes how in Johnson City, Tennessee, in 1943, her unwed grandmother struggled to keep her baby. But as months went by and her financial situation became more precarious, local doctors and social workers alerted Tann to a “very fine baby.” At eight months the baby was taken away and delivered to a wealthy couple in Knoxville, who named her Helen. The trauma of separation from her birth mother “scarred her for life,” Helen’s daughter says. “She passed that down to her kids.”

The stories in Before and After reveal how the operation’s tentacles stretched across the South, into local clinics and food kitchens. The child of an adoptee describes how in Johnson City, Tennessee, in 1943, her unwed grandmother struggled to keep her baby. But as months went by and her financial situation became more precarious, local doctors and social workers alerted Tann to a “very fine baby.” At eight months the baby was taken away and delivered to a wealthy couple in Knoxville, who named her Helen. The trauma of separation from her birth mother “scarred her for life,” Helen’s daughter says. “She passed that down to her kids.”

The quest for the truth led from hurt and doubt to answers, not all of them happy. Bess, for example, was 38 and her parents had died when she received a letter from the state of Tennessee asking for information about her adoption. “When I got that letter, it was such a shock. I had lived a lie. I wasn’t who I thought I was. … The first couple of months it affected me emotionally. I was sad. I was questioning. My aunts and uncles knew.”

She shook it off, however, and went on a search for her siblings. First, she found an older sister. When they met at the Nashville airport, “We went into each other’s arms. … I heard her whisper, ‘I love you.’ She and I are exactly alike.” One by one, Bess found seven surviving siblings: three who were also adopted and four who stayed with their sharecropper mother in West Tennessee.

These stories of children ground up in Tann’s machine are heartbreaking but ultimately satisfying. Some seized the book project and 2018 reunion in Memphis as a last chance to unravel the mysteries of their births, as well as to trade war stories and jokes about how much they had gone for on the baby market. After so long, these men and women could finally celebrate having survived and found their birth families through their own wits and determination, victims now victorious.

Lyda Phillips is a veteran journalist who grew up in Memphis and has earned degrees from Northwestern, Columbia, and Vanderbilt universities. The author of two young adult novels, she worked for United Press International before returning to Nashville.