The Call of the Tent

A writer considers the meaning of sacred space

As a child in the South I would see them: giant tents erected on fairgrounds and empty fields. Great canopies of canvas filled with folding chairs and, at one end of the rectangle, risers for the choir, an altar, and sometimes a baptismal pool. Fliers tacked to utility poles announced the event for miles. Often the revival would spread over a weekend allowing more to attend and increasing the fevered pitch of response to the Holy Spirit come down to fill believers like spring rain pouring into barrels. I could feel the runoff in the squishy ground and the air of hallelujah.

All around the revival tent the energy crackled. Hymns and spirituals serenaded even the doubters. Surely any trees in shouting distance clapped their hands. The organizers probably had Jesus on their minds while driving in the stakes, but Isaiah and King David had readied the ground.

Long before the evangelical and Pentecostal Christians of my childhood held tent revivals, my forebears built booths and tabernacles in the desert, sides open to Ruach ha-olam, Breath of the Universe that animates and sustains us, that blows life into adamah and all the creatures on Earth.

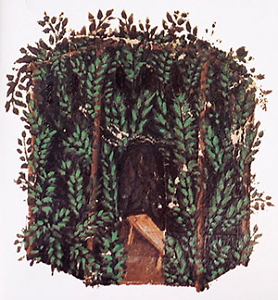

The tent as sacred space has long captured the human imagination. I remember the booth my mother made for Sukkot, the Jewish festival that dually commemorates the harvest and the 40 years the children of Israel wandered in the desert. Though it was too cold and our lives were too accustomed to cushiness to live in the sukkah for the seven days of the festival (as Orthodox Israeli Jews do), the booth summoned us to an outdoor enclosure made of branches and fabric permeable to rain, with sufficient gaps to behold the stars. Those youthful moments melded holiness with exposure to the elements, sealing the desire for this Jewish child of the South to experience the Holy Spirit in a revival tent.

***

Words were the first blanket I gathered around my shoulders and draped over dining room chairs to form a canopy of belonging I could crawl inside to meet my true self. The earliest stories I wrote at 10 and 11 held justice at their core and oddness at the edges, a recognition of my own outsiderhood once I stepped beyond the margins of my tent. I fabricated characters to make sense of what I could not comprehend alone, thus discovering the way stories so often become a literary compass to lead us through the wilderness until we find our way out or are mercifully delivered into more hospitable realms.

I spent many an afternoon on the hill in Brentwood that sloped down from our house into an expanse of meadow occasionally grazed by a few cows pastured there. Hillside, I would practice my rhetorical skills preaching to the wind and the skunk cabbage, the maples and mock orange, the darting squirrels and birds — imagining not greatness so much as efficacy: a profound inchoate longing to make a difference, to be of use. To have my words ring out as powerfully as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

All around I saw evidence of Jim Crow. In my segregated private school another third-grader objected to my assembly presentation on Dr. King, and the homeroom teacher — anxious to avoid trouble — instructed me to choose someone else.

The seeds of calling sown in the Tennessee soil and the lush humid air crackled with tongues of fire. On the green hills surrounded by lithe and stocky trees, I brought the prayer shawl fringes — tzitzit — to my lips, gathering the rent fabric of Creation in an effort to mend it.

***

Three decades later, I traveled to Cuernavaca, Mexico, to spend nine days with Benedictine nuns at a retreat center. One night after dinner, a nun named Ramona, the seventeenth child of 19 in her family, asked each of the visiting North American women if we were married. Both of the women I’d traveled with were; the college student seated with us was not.

Ramona peered at me. “You?” she asked.

I searched for an explanation to accompany my answer. How would a devout Catholic in a culture where marriage was de rigueur understand that I was not only unmarried, but I had never had a date with a man? I shook my head like a little kid asked if I’d taken a cookie from the jar.

Ramona smiled and said, “I didn’t think so. You’re just so …” she raised her hands on either side of her head and wiggled them, creating her own sign for a particular kind of energy that defies convention. Then she paused before saying, “I understand. You are married to the world.”

“Yes,” I told her. “I am.”

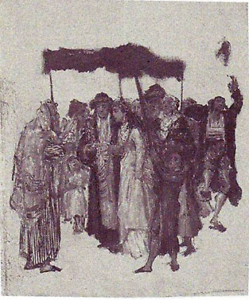

In Jewish tradition, a wedding takes place under a canopy called a chuppah, made of four poles and a piece of fabric overhead, which recalls the tent of meeting — a visible sign of God’s presence. The revival tent and the chuppah are one and the same. It’s where I stand each day to affirm my marriage to the world. But it didn’t come easily. It’s taken a while to recognize the childhood canopy of belonging forged from words is the very tabernacle I’ve sought throughout adulthood: that place of meeting where story connects us and connection hallows the ground.

Copyright (c) 2019 by Leaf Seligman. All rights reserved. Leaf Seligman, a Nashville native, writes and practices restorative justice. She lives by two maxims: “We walk in all the light we have” and “It is only in an uncondemned state that anyone can change.”