Down From the Mountain

How Hancock County embraced its Melungeon secret

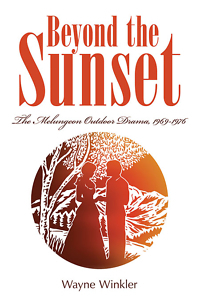

In Beyond the Sunset: The Melungeon Outdoor Drama, 1969-1976, Wayne Winkler delves into how the civic leaders of isolated Hancock County took the story of its marginalized mixed-race residents, the Melungeons, onto the stage and into a healing light.

In the 1960s, Hancock County was an isolated enclave in the heart of Appalachia, tucked into the far northeast corner of Tennessee, abutting both Virginia and North Carolina. Cut off from the outer world by steep mountains and corkscrew roads, Hancock was one of the poorest counties in the United States. Most of the population had been there for time out of mind — white farmers and merchants in the valleys and on the mountain ridges the Melungeons, dark-skinned mixed-race people first documented in the early 19th century.

In the 1960s, Hancock County was an isolated enclave in the heart of Appalachia, tucked into the far northeast corner of Tennessee, abutting both Virginia and North Carolina. Cut off from the outer world by steep mountains and corkscrew roads, Hancock was one of the poorest counties in the United States. Most of the population had been there for time out of mind — white farmers and merchants in the valleys and on the mountain ridges the Melungeons, dark-skinned mixed-race people first documented in the early 19th century.

“Hancock County didn’t have much going for it,” writes Winkler, himself a Melungeon and station manager of the East Tennessee State University radio station, WETS. “There were few natural resources to be exploited; the timber was of poor quality; there was no coal or iron to be mined; and the zinc deposit … would someday be depleted. The terrain was rough, and the county was isolated, lacking the population and resources to be an effective unit of government. The factions of the political infrastructure were unconcerned with improving the county, only with preserving their own positions. Political avenues for improvement were closed to Hancock County.”

In their desperation to pull Hancock County into the 20th century, Sneedville Mayor Charles Turner and other concerned citizens begged for road improvements, to no avail. They managed to snag a tiny industrial venture, but it brought only a handful of jobs to Sneedville, the county seat.

Finally, a 1967 study by two ETSU professors suggested a surprising way to bring visitors and their dollars into the county: staging an outdoor drama about the Melungeons.

The idea was met with skepticism. “The county was going to hell in a handbasket,” Winkler writes. “And these college professors thought the answer was to put on a play? Not only that, but a play about the Melungeons? No one in the county wanted to even acknowledge the existence of those people. Had these college eggheads lost their minds?”

For most of American history, multi-racial citizens were maligned and distrusted, a phenomenon Winkler examined in his 2004 book about the Melungeons, Walking Toward the Sunset. As a result of prejudice, Winkler notes, Melungeons and other mixed-race groups, such as the Lumbee Indians of eastern North Carolina and the Redbones of Louisiana, were forced to retreat to the mountaintops or swamps, where they managed to survive by subsistence farming, hunting, and making moonshine.

But by the mid-60s, some of that bitter prejudice had subsided. Melungeon residents, who now included bank presidents and town council members, supported the play and its themes. The leadership group gradually became convinced it was worth a try and commissioned playwright Kermit Hunter to write a script. Walking Toward the Sunset launched in 1969 and ran for five seasons with two off years before it was abandoned in 1976.

But by the mid-60s, some of that bitter prejudice had subsided. Melungeon residents, who now included bank presidents and town council members, supported the play and its themes. The leadership group gradually became convinced it was worth a try and commissioned playwright Kermit Hunter to write a script. Walking Toward the Sunset launched in 1969 and ran for five seasons with two off years before it was abandoned in 1976.

“The outdoor drama was a pivotal event for Melungeons,” Winkler said in a 2012 interview with Psychology Today. “It led to people of Melungeon ancestry proudly acknowledging their heritage.”

Claude Collins, a Sneedville leader, college graduate, and Melungeon, was the designated spokesman when tourists came to town to see the play and asked, “Where can I find a real Melungeon?” Often, he would pile them into his car and take them up onto the ridges to meet those “real Melungeons.”

“It wasn’t easy,” Collins told Winkler. “But we had to do these things to keep the play going and to keep people coming in.”

The project was energized by an influx of young VISTA volunteers who participated in the project at every step, from building the rustic amphitheater and stage to acting along with staff and students from the theater department of Carson-Newman College in Jefferson City.

Winkler, past-president of the Melungeon Heritage Association, acknowledges that even after the play’s run, Melungeon history, like that of other “tri-racial isolates,” as they are known in academic circles, is still murky.

But he looks forward, not back.

“It’s who I am because it’s who my father was,” Winkler told Psychology Today. “To be able to stand up in front of a group of people and say that I’m the descendant of a Melungeon — a term full of baggage that my grandmother was taught to keep quiet about — I’m content with that.”

Lyda Phillips is a veteran journalist who grew up in Memphis and has earned degrees from Northwestern, Columbia, and Vanderbilt universities. The author of two young adult novels, she worked for United Press International before returning to Nashville.