To Celebrate Being Alive

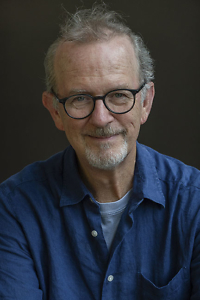

An award-winning poet reflects on the importance of daily practices

In Dailiness: Essays on Poetry, Mark Jarman never shies away from important — some might argue ineffable — topics such as faith, mortality, and selfhood. And yet he wades into these subjects with humility and an implicit acknowledgement that despite his obvious intelligence and education, he is still somebody’s son, father, teacher, and neighbor.

It is through this unspoken acknowledgement that the real wisdom of these essays is revealed. Jarman can write about seemingly unknowable ideas because he approaches them through everyday practices and objects. These pieces truly are essays, attempts at illuminating corners that are presentably dark, particularly in our understanding of devotion and its relationship to art. He lays out his mission in the preface, writing that “poetry celebrates being alive as an act of consciousness.” He convincingly makes a case for that optimistic viewpoint in the chapters that follow.

Jarman, a professor of English at Vanderbilt University, is an openly Christian poet, but if the thought of religious verse makes you think of sermons (for better or worse), let me point out that Jarman is rarely didactic. In fact, he makes it clear that certainty is the death of a good poem, even a devotional one. He praises skepticism in the works of John Berryman, John Donne, and George Herbert, among others. He also maintains that a devotional poem need not be religious at all, citing Jean Valentine’s “Lucy,” written for the discovery of — at the time — the oldest known hominid ancestor. “Lucy,” while not religious, is unapologetically reverent.

In one of the most original entries in Dailiness, Jarman argues that metaphors are powerful because they always fail in some way; the bridge between the two halves is never complete. “One of the beauties of metaphor is its promise of putting a fragmented self back together,” he explains. “One of its dynamic and exciting issues is the way that promise isn’t quite kept.” In this failure, we get a more accurate depiction of the world. Therefore we need — in Jarman’s view as well as St. Augustine’s — grace.

While primarily intellectual (though certainly not passionless), these essays do provide glimpses of the author’s life. We are given just enough personal detail to understand how poetry functions in Jarman’s world outside of his study, classrooms, and lecture halls. A review of Seamus Heaney’s translation of the Aeneid, Book VI, for example, opens with a visit to his ailing father. While the link between the two is apparent — Book VI recounts Aeneas’s descent into the underworld to say goodbye to his father — I was still unprepared for the moving ending of this essay in which Jarman helps his father prepare a collection of sermons for publication.

His father sums up the book’s message to his readers: “You are not finished.” Jarman spells out for us that this could also be the tagline for Book VI of the Aeneid. Aeneas is not finished with his accomplishments, of course, but neither is the ghost of his father, doling out advice even if he can’t physically embrace his son. It’s a clear connection that seems inevitable after you read, just like a perfect line of a poem.

His father sums up the book’s message to his readers: “You are not finished.” Jarman spells out for us that this could also be the tagline for Book VI of the Aeneid. Aeneas is not finished with his accomplishments, of course, but neither is the ghost of his father, doling out advice even if he can’t physically embrace his son. It’s a clear connection that seems inevitable after you read, just like a perfect line of a poem.

In a lecture originally written for the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, Jarman illustrates the considerable challenge of composing such a perfect line. Perhaps most compellingly, he shares multiple drafts of his own poem “Eocene Beech Leaf,” and the final version is nearly unrecognizable from the first. Indeed, if the title weren’t the same, I’d question whether Jarman wasn’t having a bit of a laugh with us. But no, we can witness his serious intent, how he wrestles with the concept and lands on an 11-line beauty that concludes,

Startling in a way to see so far back—

as if we’d found between leaves of a book

a picture of ourselves from much younger days

and remembered nearly everything about it

except just why we’d put it there.

And while “Eocene Beech Leaf” is not an ars poetica, this stanza is an apt metaphor — flawed, of course — for how this poem came into being.

And how does such a poem come into being? Through work, Jarman posits, and a daily habit of writing. He backs up this advice with related exhortations from W.B. Yeats, Robert Frost, Jane Kenyon, Adrienne Su, and others. But my favorite bit of tough love comes from Jarman himself: “Readers of poetry don’t care how long it took you to write the poem.”

As you might have guessed from the book’s title, dailiness is the primary theme — but dailiness need not be dull. In “The Story of a Feeling,” Jarman explores the pleasure and usefulness of repetition. He considers why it occurs so frequently in poetry, as well as how it relates to prayer. As with other chapters, he uses examples both canonical and contemporary. Brian Wilson gets him started, though, with a lyric from the Beach Boys song “Do It Again,” reminding us that repetition can, yes, be poetic and liturgical, but it can also make you dance.

“We pray for the same reason we write poetry: to understand and be understood,” Jarman writes. “And a poem, like a prayer, needs to be about something — something worth repeating.” It’s an uplifting way to think about writing daily — or putting our kids to bed or walking our dogs or calling a friend. These are actions worth repeating, and these essays are worth rereading.

Read an excerpt from Mark Jarman’s most recent poetry collection, The Heronry, here.

Read Chapter 16’s interview with Mark Jarman here.

*Photo © 2020 by Miriam Berkley. All rights reserved.

Erica Wright is the author of four crime novels and two poetry collections. Famous in Cedarville was released in October 2019. Now a senior editor at Guernica, she grew up in Wartrace and received her M.F.A. from Columbia University.