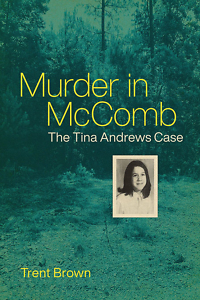

Mississippi Murder

Historian Trent Brown unpacks the meaning of the 1969 murder of a young girl

In August 1969, a 12-year-old girl named Tina Andrews was killed and deposited in an oil field outside McComb, Mississippi. In Murder in McComb, historian Trent Brown revisits this case. Along the way, he ponders the larger forces that shaped how the people of McComb interpreted the crime, the trial, and the main characters in the tragedy.

Brown, a McComb native, earned his Ph.D. in history from the University of Chicago and is now a professor of American studies at Missouri University of Science and Technology. He is the author or editor of four previous books, including Ed King’s Mississippi: Behind the Scenes of Freedom Summer. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: You grew up in McComb. How did that stimulate your interest in this story? How did it shape the writing of the book?

Trent Brown: When Tina Andrews was murdered, I was 4 years old; not surprisingly, then, I have no memory of hearing anyone discuss the matter. However, my grandmother operated a beauty shop in the city, where I am certain the case would have been a topic of intense speculation. Members of my family, it turns out, attended the trials, served on the jury, and even went to school with some of the principal figures in the case. But that was all news to me when I began writing the book.

Living in McComb in the late 1960s and early 1970s, I knew very little about the city’s recent history. I learned about the Andrews case only a few years ago. How, I wondered, could the murder of a child in my hometown go unresolved? As I began writing the story, I saw more clearly how this case and McComb’s broader history were shaped not only by matters of race, but also by ones of social class. The Tina Andrews case demonstrates how considerations of power and respectability formed lives in the community then and later.

Chapter 16: What are the facts of the case? What do we know?

Brown: In August of 1969, the decomposed body of Tina Andrews, a 12-year-old girl, was discovered in an oil field outside McComb. Partially clothed, she had been shot in the head. For months, local law enforcement authorities investigated the matter, interviewing a number of suspects. But while there were many leads, there were no arrests. Over a year later, however, a witness came forward with information about what had happened to Andrews. Significantly, the witness went directly to the district attorney and not to the police, whom she feared and distrusted. She said that two men had picked up her and Andrews outside a local club and took them to the oil field, probably with sexual designs on the girls. The witness said that she had been able to escape the men, while Andrews did not.

The district attorney subsequently secured indictments against two McComb police officers. One of them was tried twice and ultimately acquitted. Charges against the other were dropped. In the trials, the defendant consistently maintained that he had nothing to do with the murder of Andrews. The state was unable to persuade two juries that he had. No one was ever convicted of the crime.

Chapter 16: All the main figures in this book are white. Yet you argue that the civil rights movement had a profound impact on how McComb residents considered the case. Why?

Chapter 16: All the main figures in this book are white. Yet you argue that the civil rights movement had a profound impact on how McComb residents considered the case. Why?

Brown: McComb had a well-earned reputation as one of the most violent cities in a state that was perhaps more resistant than any other to the civil rights movement. All the basic institutions of the town — the courts and law enforcement authorities, especially — had been shaped by decades of Jim Crow. But people with power and authority in McComb recognized how close the city had come to anarchy in the mid-1960s. I don’t use the word anarchy lightly. In the summer of 1964, some white McComb residents fought the civil rights movement with a wave of bombings and other domestic terrorism that was shocking even by the era’s standards.

By the early 1970s, however, many white people in the area wanted not only to put those years behind them, but also to do what they could to maintain law and order, as they viewed it. Black McComb residents had mounted a powerful challenge to the old order in the 1960s. But many white residents were determined by the early 1970s to reestablish control, and if this meant supporting local institutions such as the police department against claims of justice for a socially marginal girl, so be it. This was the context in which Andrews’ murder was investigated and her accused killer was tried.

Chapter 16: We might assume that the murder of a young white girl in the Deep South would inspire widespread outrage and demands for harsh punishment. But that wasn’t the case with Tina Andrews. Why?

Brown: Andrews came from a modest social background, as did the state’s main witness. The men arrested for her murder were police officers. In the two trials that occurred in 1971 and 1972, the very effective defense attorney essentially framed the case as one of reputable versus disreputable people. Also, the two district attorneys who prosecuted the case were not dealt a strong hand of cards. The state’s main witness had not come forward until well over a year after the murder. When she testified, she was 15 years old, an “unwed mother,” as the defense constantly pointed out. There was no physical evidence tying anyone to the crime: no blood stains in an automobile, for instance, no hair or fibers tying the defendants to the victim, and no one who had seen the actual murder of Andrews. The state’s case against the defendant was largely circumstantial.

Area people — those on the jury and those who were not — were essentially asked to consider whether the McComb police department employed child murderers or if a girl like Andrews simply met her death at the hands of unknown parties. In the eyes of some people in the community, Andrews ultimately seemed not to matter very much because of her social background.

Chapter 16: How do the people of McComb think about this case now? How does it fit into their sense of the town’s history and identity?

Brown: People who are not of an age to remember the crime generally know little about it. That says something, I think, about how community memory works. Had Tina Andrews come from a prominent white family, or had she been an African American child, her murder would have fit more easily into familiar narratives about Southern crime. People who do remember the case often say that the failure to convict anyone speaks to broader issues of corruption in the community.

Many rumors continue to circulate in the community. One can hear that Andrews was murdered to silence her about salacious things she knew about prominent men in town. There is no doubt that McComb had been a violent place. Its police department employed men who worked with relish to suppress the civil rights movement in town. But the two district attorneys prosecuted the case vigorously. There is no evidence that either one of them did other than to try his best to win justice for Tina Andrews.

Chapter 16: “My hope,” you write, “is that the book will suggest how much remains to be written about the history of the Deep South in recent decades.” What might this history look like?

Brown: Thanks to the work of many historians, we know a great deal about the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, especially at the local level. But the Deep South in the years after the civil rights movement is relatively underexplored territory. Southern communities were shaped and continue to be shaped by practices and institutions formed over half a century ago. So many of the issues the Deep South wrestles with currently — politics and elections, economic development, public education, and crime and incarceration — are informed by the history of the recent past. What the Tina Andrews story shows, I think, is the continuing significance of social class in the Deep South, as well as the profound influence of gendered ideas of behavior and respectability. Those issues are ones that deeply merit fuller exploration.

Aram Goudsouzian is a professor in the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.