What Could and Could Not Be

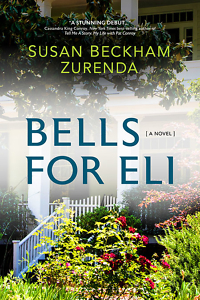

A close bond between cousins is tested in Susan Beckham Zurenda’s debut novel

“From time to time, Mama proclaimed I ruminated too much,” says Delia Green, the narrator of Susan Beckham Zurenda’s debut novel, Bells for Eli. What Delia mostly ruminates about is her close relationship with her cousin Eli, whose family lives across the street in the small town of Green Branch, South Carolina. The two cousins’ worlds are changed forever in 1959 when Eli accidentally swallows lye on the day before his third birthday.

Although he narrowly avoids dying, Eli is forced to endure painful and debilitating treatments for years, breathing through a tracheotomy and “eating” via a hole in his stomach until he is 10. Eli’s differences set him apart from other children, and Delia – only a few months older – becomes his best friend and protector. When Eli eventually returns to school, he is bullied by the boys and shunned by the girls. “They said he was a pretty boy, and he was,” Delia explains. “His skin was soft and white as vanilla ice cream, and he had his mother’s wide-set olive eyes, laced with heavy lashes. His nose was nearly perfect, straight and slightly tipped up, like a Walt Disney movie prince. But beauty made Eli’s situation worse. It made him seem like a sissy.”

Eli bears the cruel treatment of his peers with a fiercely stoic attitude that puzzles Delia, who only wants to help him. She says, “Part of me was relieved Eli kept the intimacies of his pain to himself, but another part of me wished for him to release his feelings to me so that I could feel what he felt. But I didn’t probe. I took my cues from him.” As they progress from childhood to adolescence, Eli becomes more confident and self-assured, although the change is partly fueled by a growing dependence on alcohol and drugs. While frequently tested, the cousins’ bond remains unbroken as Delia narrates the stories of both their lives — high-spirited exploits, romances begun and ended, joy-filled wonder at the world, and life’s inevitable losses. By the time they go to college, the winds of change blowing through American society in the 1970s buffet Delia and Eli, with tragic results.

Eli bears the cruel treatment of his peers with a fiercely stoic attitude that puzzles Delia, who only wants to help him. She says, “Part of me was relieved Eli kept the intimacies of his pain to himself, but another part of me wished for him to release his feelings to me so that I could feel what he felt. But I didn’t probe. I took my cues from him.” As they progress from childhood to adolescence, Eli becomes more confident and self-assured, although the change is partly fueled by a growing dependence on alcohol and drugs. While frequently tested, the cousins’ bond remains unbroken as Delia narrates the stories of both their lives — high-spirited exploits, romances begun and ended, joy-filled wonder at the world, and life’s inevitable losses. By the time they go to college, the winds of change blowing through American society in the 1970s buffet Delia and Eli, with tragic results.

Zurenda’s emphasis on the power of words — to both hurt and heal — is poignantly portrayed in Bells for Eli. When a schoolmate admits she has lied to Delia, she says, “The words felt like a wind blowing me backward, the kind of strong gust to make a child lose her balance, and for a moment I couldn’t speak.” Later, Delia regrets a rare moment of anger with Eli in which she draws attention to his disability: “My words lay all around us, invisible blocks to stumble over. I’d said he was weak and different, and in shaming Eli with the truth, I’d shamed all of us.”

But even as the cousins grow and their lives take different turns, it is their love that endures — a love that changes with time but never diminishes. When an innocent incident causes their parents to react harshly, Delia says, “I lay awake much of the night, both angry and shamed … Knowing what would surely happen to Eli when nothing was his fault. Imagining the scene. Fearing the beating. Knowing our days had now divided between childhood and the beyond. I tried to understand what could and could not be. Loving Eli.”

Tina Chambers has worked as a technical editor at an engineering firm and as an editorial assistant at Peachtree Publishers, where she worked on books by Erskine Caldwell, Will Campbell, and Ferrol Sams, to name a few. She lives in Chattanooga.