Writing About the Tough Stuff

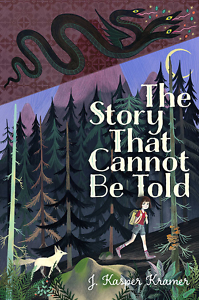

J. Kasper Kramer’s debut middle grade novel celebrates the resilience of its young protagonist

The Story That Cannot Be Told, a novel for middle grade readers, portrays one brave girl’s fight against injustice during the months leading up to the Romanian Revolution of 1989. Ten-year-old Ileana and her parents live in Bucharest and struggle to survive amid mandatory curfews, severe rationing of food, and limited access to everything from housing to electricity to art of any kind. It’s the only life Ileana can remember, and she writes about it in her beloved “Great Tome,” a homemade notebook filled with stories.

The repressive government’s spies are everywhere and Ileana’s uncle, an outspoken poet, may be endangering the family. After a series of troubling events, Ileana’s parents resolve to send her to the countryside to stay with her grandparents — but that ‘s not the end of her trials. “My father had betrayed me. My mother’s life was in danger. My uncle was probably dead,” Ileana says. “I was traveling alone to the other side of the country – to a place that I knew only from pictures. With nothing more than a letter, I’d have to convince people who’d never met me to take me in and use their rations to feed me. I’d have to convince them to keep me a secret.”

The repressive government’s spies are everywhere and Ileana’s uncle, an outspoken poet, may be endangering the family. After a series of troubling events, Ileana’s parents resolve to send her to the countryside to stay with her grandparents — but that ‘s not the end of her trials. “My father had betrayed me. My mother’s life was in danger. My uncle was probably dead,” Ileana says. “I was traveling alone to the other side of the country – to a place that I knew only from pictures. With nothing more than a letter, I’d have to convince people who’d never met me to take me in and use their rations to feed me. I’d have to convince them to keep me a secret.”

Author J. Kasper Kramer (the pen name of Chattanooga writer Jessica Miller, a Nashville native) skillfully weaves historical fact with Romanian folklore and Ileana’s own adaptations of classic fairy tales to portray a society in crisis. The Story That Cannot Be Told is a tribute to the tenacity and resilience of the Romanian people. By turns charming and heartbreaking, the book is beautifully written and, like all the best fairy tales, its deceptively simple style illuminates powerful truths.

Chapter 16: Why is it important to write literature for children about difficult topics like the Romanian Revolution? What do you hope young readers will take away from Ileana’s story?

Kasper Kramer: When complicated, frightening things happen in the world — war and famine, political unrest, even genocide — children experience the hardship and horrors alongside adults. I think we often lean away from this truth in media because it upsets us, and we hide difficult topics from children out of a desire to protect them or a fear that they won’t understand.

But if we don’t write about the tough stuff — and if we aren’t honest in our portrayal — the children who’ve experienced hardship won’t have stories to help them cope. (And aren’t those kids the ones who need stories most of all?) I also believe writing about difficult situations helps create empathy. Number the Stars [by Lois Lowry] wasn’t an easy read for me as a child, but it set the tone for how I felt about the Holocaust for the rest of my life, and that was important.

I suppose I hope that young readers will connect to Ileana and feel empathy for people living in difficult times. I hope they’ll share her desire to stand up for what they believe in and to tell their own stories.

Chapter 16: Ileana’s family spends a lot of time trying to protect her, even as she and her friends make preparations to face their enemies in battle. Do you think that adults tend to underestimate the ability of children to grasp and adapt to difficult situations?

Kramer: Absolutely. I’ve been a teacher for over a decade and have worked with children of all ages. I was even a kindergarten teacher for a few years at an international school in Japan. One of the things that never ceases to astonish me is how resilient and clever children are. They often know much more about what’s going on around them than adults realize, and they’re quite capable of handling very challenging situations. Sometimes they even respond better than adults!

I believe it’s usually out of our desire to protect children that we hide things from them — I’ve been guilty of this myself. But no matter what good intentions adults have, I think it can be dangerous to hold our children too closely. If Ileana’s parents had been more open with her about their situation, she might have made different choices. Things might have turned out better for everyone.

Chapter 16: You have not shied away from portraying bullying, torture, and death in a book for young readers. How do you decide where to draw the line at such subject matter when writing for children?

Kramer: When I first drafted my debut, I wasn’t sure who it was for. I just wrote the story I wanted to write in the voice of the character I thought was best to tell it. When The Story That Cannot Be Told sold as a middle grade novel, I was thrilled. It felt like all these doors I’d dreamed about were opening — doors that led to school visits and workshops with young, aspiring writers, like the ones I’d once attended. But it would be a lie to say I wasn’t a little worried that my novel being marketed as middle grade might mean some of the more intense parts — parts I felt were thematically integral — would have to be cut.

While working with my amazing editor, Reka Simonsen, we talked often about “the line,” but we also made certain my book didn’t lose anything I felt was important to message, character, or tone. More often than not — surprising as it may sound — the changes we made were mostly at the sentence level. We pulled back from graphic descriptions, honed in on character reactions, and worked always toward creating empathy.

It’s interesting to add, though, that after these changes — changes made specifically so the book would be more appropriate for a middle grade audience — translation rights sold to Wunderraum, a lovely adult literary imprint of Random House in Germany. The book comes out there in May 2020, titled The Story Collector.

So I think there’s a discussion to be had about the overall concept of “the line” itself. Where does it fit between children’s literature and adult books? Does it even really exist?

Chapter 16: Throughout the book, Ileana writes her own triumphant endings to traditional folktales in which female characters have not typically been the victors. Why did you decide to incorporate these re-told tales into Ileana’s story?

Chapter 16: Throughout the book, Ileana writes her own triumphant endings to traditional folktales in which female characters have not typically been the victors. Why did you decide to incorporate these re-told tales into Ileana’s story?

Kramer: In traditional fairy tales and folktales, women are typically treated terribly. They’re portrayed as unintelligent or nagging or selfish. Sometimes their only purpose is to be punished — to show readers the unfortunate consequences of some immoral choice. Other times, their existence in a story is only as a temptation for the hero, an object (often sexual in nature) used to lure the hero away from his quest or his good sense. In the rare cases where women are presented as positive characters (or, even less frequently, heroines), they’re allowed a very limited set of qualities: modesty and virginity, selflessness and submissiveness. Women in such stories can be good mothers or good wives or good daughters (who become good wives) and virtually nothing else.

I wanted folktales in my book because I love them — for many, many reasons — and because I think we’re exposed to very little Romanian folklore here in the U.S. But I also believe that staying too true to the original narratives of these tales can be harmful. On top of that, retellings are more fun because it makes for good humor when you poke at outdated tropes.

Chapter 16: Ileana’s grandmother tells her, “There are ghosts everywhere, child. The world is full of them.” What purpose do fantastic elements serve in a book about an actual historical event?

Kramer: Fantasy, when thoughtful, gives writers the opportunity to talk about difficult issues with a bit of distance between the reader and the real world. People have a hard time accepting new ideas. We react aversely to things that challenge our frame of thought as a self-defense mechanism. Adding fantastic elements to historical fiction — especially when that historical fiction serves as a close commentary on modern issues — lightens the impact of difficult topics. I think it’s also important to note that historical fiction runs a higher risk of being dry or boring — too stuffed with facts and dates or textbook language. Whether I’m writing for children or adults, that’s not a risk I’m ever willing to sit quietly with.

I love fantasy and science fiction and horror. I always have. So it’s just natural for me to incorporate fantastic elements into my work, no matter the overarching genre. For instance, my next novel, The List of Unspeakable Fears, is a historical fiction set in 1910 New York City on the very real North Brother quarantine island. Young Essie, an Irish immigrant girl who’s lost her father, is forced to move to her suspicious new stepfather’s dreary home. There are themes of grief and illness, prejudice and overcoming fears. However, there’s also an important fantastic element to the story. Something frightening — and perhaps even supernatural — is happening on North Brother Island, and Essie has no choice but to confront it.

Chapter 16: A central theme of the book is the power of art, especially storytelling, to initiate change. Ileana says, “The most dangerous thing of all was to write.” What has writing this book taught you — or reinforced for you — about that power?

Kramer: I think it’s important to note that when corrupt governments take control, one of the first things they do is put systems into place that work to silence not just intellectuals, but artists. We saw this in Nazi Germany. We saw this in Communist Romania. And we’re seeing it now today.

People like professors and scientists are targeted because they have the power to spread knowledge. Writers, directors, actors, musicians — they have that power, too. And in many cases, they have the ability to reach a broader audience and to trigger a more emotional (and therefore more immediate and impactful) response.

Writing is dangerous in the way that telling the truth can be dangerous. There will always be people who react negatively — usually because they’re afraid — and these people will work to silence you.

But that makes it all the more important to keep telling stories as loudly as we possibly can.

Chapter 16: Although the novel is based on the history and culture of Romania, what aspects of the story draw from your personal experiences? Did you perhaps cherish a Great Tome of your own?

Kramer: In my author’s note, I talk about how Story was inspired by my Romanian friends in Japan. Many events in the book come from their personal experiences growing up under Communism. In fact, that’s why I knew Ileana needed to be a child — she’s about the same age my friends were in 1989. The stories they told me were from a child’s perspective, and I couldn’t separate that from my own retellings.

Of course, there’s a great deal of me in Ileana, too — obviously her love for stories and desire to be a writer. My own version of the Great Tome existed in a rainbow-colored collection of floppy disks which held all my books.

Also, just like some of Story came from my friends’ real family histories, some came from my family history, too. For instance, my mother’s great-uncle Germaine was a fighter pilot in World War II. After crashing in occupied France, he crawled inside a haystack to hide. The only reason he survived was because a young farmgirl secretly brought him raw eggs to eat. I won’t give away the scene that inspired, since it’s a bit of a spoiler, but if you’ve read the book, you can probably guess!

Chapter 16: How does the reality of having published your first book compare to your expectations?

Kramer: I hate complaining about anything when it comes to this career, because I’ve dreamed about being an author my whole life. I told my kindergarten teacher about it. I spent my snow days in middle school typing away and my summers in high school at writers’ workshops. I can’t even begin to guess how many times I broke down over the years, devastated, because I was sure I’d spent my life dreaming too big — that this would never happen.

So the fact that I have a book on the shelf, that it’s going to be translated into multiple languages, that I already have my next book under contract — all of these things are still so stunning to me that sometimes they don’t even seem real.

But it’s also very true that when you get what you set your heart on, the goalpost can start to shift. It’s hard not to compare yourself to others. It’s easy to get lost in all the noise. Lists, awards, blurbs, reviews, sales — it goes on and on and on. The highs and lows are high and low. Fortunately, though, I know these feelings are normal. I’m part of some wonderful groups of authors, like Novel Nineteens and Class of 2k19. We chat online, support each other on social media, and meet up at retreats. We plan signings and conference panels together. It’s like having the coolest coworkers in the world — except, really, they just feel like close friends.

I’ve always been a really solitary writer, and I’m a bit of a recluse in my personal life, so I think that’s the biggest surprise to me about having a book published. I suddenly feel like I’m part of a community. And I’m so, so happy to be here.

Tina Chambers has worked as a technical editor at an engineering firm and as an editorial assistant at Peachtree Publishers, where she worked on books by Erskine Caldwell, Will Campbell, and Ferrol Sams, to name a few. She lives in Chattanooga.