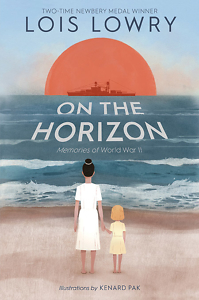

Lois Lowry Broadens Her Horizons

After two Newbery Medals and more than 40 books, Lois Lowry writes her first book in verse

In On the Horizon, acclaimed children’s author Lois Lowry explores the history of World War II through the stories of those who died in the attack on Pearl Harbor and the bombing of Hiroshima. She also draws on her own experiences as a child in Hawaii and post-war Japan. The book is written entirely in verse. Chapter 16 talked with Lowry by phone about writing in this form for the first time, what she thought of the film adaptation of The Giver, what surprises her about children’s literature after decades in the field, and more.

Chapter 16: Some of these personal stories in the book are just remarkable — that this home movie exists of you on the beach with the Arizona in the background before the bombing, as well as figuring out that Allen Say and you once spotted each other as children in the 1940s in Tokyo. Can you talk about what that moment was like for you when, as you mentioned in the book’s closing note, your friend John spotted the ship on a home movie?

Lois Lowry: Yes. You know, I was born long before television and long before video cameras. But my father was a camera nut, though that wasn’t his profession, and he always had very professional equipment. So, we ended up with very good home movies, instead of what the usual was at that time of people waving at the camera and looking embarrassed.

At any rate, in my childhood every now and then we would convince Dad to get out the projector and put up the screen, and Mother would close the draperies. And we would sit around watching, once again. Now and then Dad would, at our request, run things backwards, which just seemed so amusing at the time. This all seems so primitive now.

As my father got old, and of course television intervened, we never saw those old home movies again for many years. But Dad was getting old and I was visiting him, and we talked about those films. And he mentioned that they were deteriorating. So, I brought them back to Boston with me and found somebody at MIT — I mean, nowadays this is standard procedure, but at that time it wasn’t — who could save what they could. Some of it was lost. I’m the only person in the world who regrets this loss, but there was a wonderful sequence of me at age two, naked on the bathroom floor, carefully powdering and diapering my doll. Anyway, that’s lost to history. And maybe just as well.

But they saved what they could and put it on videotape. And I had just bought a VCR — early days. And I had company over, and before I sent that videotape to my dad, I made my friends watch this film. And it was John, who had been an Annapolis graduate and captain of a nuclear submarine, who suddenly said, “Stop! Do you know how to go back and replay that?” And I did. And he pointed it out. And it was surprising to me at the time that, all the times I’d seen that little sequence of me playing on the beach, I had never looked beyond me. Narcissism, I guess. But it was a cute scene of me playing with my little shovel. I had never looked beyond and seen what he saw.

And once he pointed it out, it began to haunt me. And I didn’t know what to do with that information — the fact that I had played so happily on the beach, while all those young men slowly moved past on the horizon and would be dead soon. So, that just stayed in my consciousness. And it was much later after encountering and getting to know Allen [Say], who has become a good friend — all of it fell into place eventually. That’s when I sat down and put it together in this way.

And I don’t know what prompted me to do it in the form that it takes. It just seemed to want me to tell it that way. And, of course, I did a lot of research.

Chapter 16: As for the form you chose, this is your first time writing in verse, right?

Lowry: Yes. I’ve done little verses for — you must have known or been familiar with [poet and anthologist] Lee Bennett Hopkins.

Chapter 16: Yes.

Lowry: He was a friend, and occasionally at his request I would do a little verse for one of his anthologies. But, no, I had not used this form before. It’s interesting that suddenly this year, perhaps last year, it’s become a very popular form. I think these things are maybe just out there in the atmosphere, and we tap into them at the same time.

This lent itself to that, particularly when I began doing research about the individuals. I wanted to focus on individuals affected by these events. And then as I selected the ones on whom I would focus, it felt as if the book — or the piece or whatever I was doing — was coming together in fragments. And maybe that’s why the form lent itself to that, rather than an ongoing narrative. You know, I could have tried to do that, but I don’t think it would have worked. So, this worked better.

The hard part was choosing whom to focus on. There were, sadly, so many. There were over 1,100 young men on that ship. And then of course there were close to 100,000 victims in Hiroshima. So, in reading about the individuals, sometimes one little detail would grab my attention, and that person would be the one that ended up in the book.

Chapter 16: You have three major parts here — the Pearl Harbor perspective, stories of those civilians in Hiroshima, and thoughts on your life in Tokyo. Did you know right away that you wanted to structure the book in that way? Or did that come to you later?

Chapter 16: You have three major parts here — the Pearl Harbor perspective, stories of those civilians in Hiroshima, and thoughts on your life in Tokyo. Did you know right away that you wanted to structure the book in that way? Or did that come to you later?

Lowry: I think I started — it’s hard to remember my thought process — I think I started out just with the ship, the Arizona. And then things began to fall into a logical sequence, I think — in part, [because of] my ongoing friendship with Allen. He lives on the West Coast, but I do talk to him via email now and then. Whenever I get an email that begins with “konnichi wa,” I know it’s from him. I realized [all of this] fell together in a kind of sequence and had a relationship. I didn’t attempt to define the relationship. I hope that emerges out of the book itself — the connection that we have to each other. I guess I tried to say that when I [write about] the boys on the ship and the child on the beach and then, later, Allen’s and my connection. All of us out there, individually, in some way are connected to each other. I think that’s what I’ve tried to say throughout my whole career, but certainly it comes full circle in this book.

Chapter 16: Are your childhood memories from both Hawaii and Japan vivid for you? Are they easy to recall?

Lowry: I was born in Honolulu, and so, like everyone, my first memories are fragments and kind of ethereal. My literal first memory is of flowers. I’m uncertain of the place. It’s a doorway, surrounded by flowers. But when I described that memory to my mother, she told me that was the doorway of our home in Honolulu. Actually, I have a very clear memory of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. We were not in Honolulu at the time. We had left there. We were now in New York. But I remember that day, because of course it was a day of great consternation in our house. I wasn’t aware of what exactly was happening, but I remember my mother telling my father with some urgency that he should put his uniform on. It was a Sunday, and he was in civilian clothes. So, that’s a very clear memory. The memories before that of Honolulu are just these fragments of my sister. I lost my sister young. She died young, so I cherish those memories of her — you know, playing with me, teaching me things. But like all early memories, they are just kind of little bits and pieces.

The memories of Japan are very different, because I was, by then, at an age where those memories are more solidified. I have very clear and definite memories of my days there.

Chapter 16: You mentioned a moment ago, as well as in the book’s closing note, that the home movie haunted you. But it took decades for you to write this book. Do you know why it took that long? Was it perhaps something you had considered before but not started?

Lowry: I had not considered writing about it, because there was no story there, really. You know, I was accustomed to writing fiction, sometimes autobiographical fiction — but with a beginning, middle, and an end. Yet what was haunting me was just one little piece of an extremely long and international narrative. So, it didn’t lend itself in the early days to being written about. It just lay there in my consciousness. It wasn’t until later … you know, I have often — in the Newbery acceptance speech, I think I talked of Allen’s and my connection — and people have always said, “Oh, you ought to write that.” And Allen and I talked about it. We never came up with a vehicle or a way of describing this unusual moment in our middle childhood — and then not meeting, really, until we were probably in our 60s. And there didn’t seem to be anywhere to put that together either. So, I don’t know what it was that made me finally figure out, intuitively, how to connect the dots, as it were, and put this book together.

Chapter 16: Yes, it seems like maybe, as you’ve said, the realization that you could write this in verse made have had a huge part in that. It really does lend itself so well to that.

Lowry: Well, for one thing, the story of Allen and me, when we met in Miami at the Newbery event, whatever year that was (1994, I guess) — he gave me a copy of his beautiful book, Grandfather’s Journey, and he drew a little picture in it when he signed it for me. And I gave him a copy of The Giver, and I signed my name in Japanese. And he laughed and asked me how I happened to be able to do that, and I said I’d lived in Japan as a kid. And he asked where I’d lived, and he said, “That’s where I lived.” And we went down this path of narrowing and narrowing it, until suddenly he said, “Were you the girl on the green bicycle?”

Chapter 16: Wow.

Lowry: It was a startling moment. And both he and I have occasionally described that moment, and people have been so astonished by it. But to be honest, if you were to write such a moment into a book, into a novel, say, an editor would make a note on the side, saying: “Credibility issues here.” It strains belief. So, in fact, I didn’t even attempt to do that in this book. I perhaps mentioned it in the afterword. I don’t think I even tried to put it in as an aha moment, although it certainly was one.

Chapter 16: What was it like for you to write in poetry for the first time? You also write in a variety of styles, such as free verse, haiku, etc.

Lowry: Yes, a little of everything. You know, I could have meticulously done each little piece in a specific form, rigid. It didn’t seem to lend itself to that, although I did include some very structured pieces. And I can’t explain how I made those decisions. It was just that some things lent themselves to a form that others did not. That was intuitive, I think. And I must say I was grateful that the editor, Margaret Raymo at Houghton Mifflin, didn’t say, “Would you please do this all in, you know, sestinas?” She just let it go the way I felt that it should.

Chapter 16: Right. And the illustrations add so much, too. They are also haunting in their own way.

Lowry: I have not met Kenard Pak. I would, of course, loved for Allen to have illustrated it. But he was booked solid. He and I, incidentally, are both the same age, though he’s quick to point out that I’m five months older. But I’m about to turn 83, and he’ll be 83 this summer. Amazingly, we’re both still working hard, but he is booked solid. He said he had four contracts with deadlines, and he just couldn’t take on anything else. So, as usually happens, the editor is the one then who finds the right illustrator, and so it was Margaret Raymo who hired Kenard, who lives in San Francisco. He and I did an NPR radio interview together recently, but we, of course, were each on an opposite coast, and we were meeting for the first time with headphones over our ears.

Chapter 16: You said you and Allen didn’t meet till you were both in your 60s, right?

Lowry: Well, I’d have to do the math. … I’m about to be 83, and we met at the convention where Grandfather’s Journey and The Giver won the Newbery and Caldecott Medals. Both books, coincidentally, had the same editor. And so that was the 1994 Newbery Medal. So, let’s do the math. That’s 26 years ago. Let’s say we were 57. I don’t know when it was in relation to our birthdays. So, it was a long time ago.

Chapter 16: That is incredible. That’s a special friendship.

Lowry: Yes, and I’ve known Allen well in those years since, though we’ve never lived in the same place. Whenever I’m in the Northwest, I stop and see Allen. And once I remember, there was a conference in Denver, and Allen called me and he said, “They’ve invited me to speak at a conference.” And he said, “Of course I said no, and then they told me you were coming. Is that true?” And I said, “Yes.” And he said, “Well, in that case, I’ll come, but can we go off and have dinner together just by ourselves?” So, at that time … I don’t know if you know the Tattered Cover — everybody who loves books knows the Tattered Cover in Denver — and we sat and had dinner together. And I remember he was working on a book called Kamishibai Man. And the Kamishibai were people who were prevalent in Tokyo in those years when we were children there, and so we talked about that and about his memories — and mine — of that phenomenon.

Chapter 16: You mentioned your research for On the Horizon. What was that like?

Lowry: Well, you know, each person I found — it’s amazing what you can find on the internet. And then I did find a hard copy of some of this information as well. But I found short bits of information about each person, both sailors and a contingent of Marines on the Arizona. And in some cases, that was all I was able to find — so-and-so, age whatever, from wherever. But in some cases, I could click on links and I could go back and find other bits of information, more and more. You go deeper and deeper.

For example, one that I used in the book was — I don’t have it here in front of me, so I don’t have his name — but he was from a farm in Iowa. And his official information did not tell me this, but when I clicked on his name, I discovered he was the youngest of three brothers. And his oldest brother had died in World War I, and his second brother, at the age of 14, had been struck by lightning when bringing the cows in from the pasture. And he was the last remaining brother. But the thing that I found on the internet was an old newspaper article, an interview with his mother, in which she said — and I use this in the book — “I had bad luck with all my boys.” That just struck me as such a stark and tragic statement. I can only picture — I have no idea who she was or what she was like — but I picture a farm woman in Iowa and her saying that with … well, talk about a stiff upper lip. So, that was one that struck me so that I used that young man.

And there were others, of course. Just the fact that there was a pair of identical twins on that ship was startling.

So, now I’ve forgotten your question, but it was about doing the research. Some were just a name and an age and a photograph. There were official photographs of all of them. And I didn’t find out anything more than that.

I had hoped, actually, to give it some diversity, but the fact is it was a segregated military at that time. So, there were no African American sailors on that ship. There were some Asian Americans, but they were all, in those days, relegated to working in the kitchen. And there was little information about them. So, there’s very little diversity. The ones who are in the book are all white sailors and a couple of Marines. I was sorry for that.

At any rate, out of 1,100, I could have plucked, almost at random … each person has a story. And in this case, it was 1,100 tragic stories.

Chapter 16: Switching gears here, do you have anything to do with the film adaptations of your books? I wonder what you thought of The Giver, the movie adaptation. I also read that they’ll be adapting The Willoughbys, yes?

Lowry: Yes, that will be out on Netflix in April.

Some years ago there were a couple of TV films of books of mine. This is no longer true, but TV adaptations at that time tended to be cheaply made, and that showed in the movies of my books. They were pretty bad!

Chapter 16: Are you a consultant on these kinds of things?

Lowry: Not generally. I was fortunate with the movie of The Giver in that they did include me. Not as a consultant, and I didn’t write the screenplay. But the director, whom I liked very much, had me to his home in Los Angeles, and we talked by Skype to a person who was, at that time, in South Africa, designing costumes and sets. So, we were able to look at some of those things. I vetoed a costume that they had tentatively planned for Fiona, the young girl in the movie, because I said it was too sexy. The clothing in the place at that time would not be. They did ask my opinion on things, and sometimes they took my advice, and other times they ignored it. Then they invited me to go to South Africa to watch a few days of the filming, which was very gracious and probably very expensive for them to schlep me over there. But it was fun.

There were things that I liked about the movie, and there were also things I hated. And I think probably any author would say the same thing about any adaptation. And one of the things I liked — and liked better than I had done it in the book — was the description of the living quarters of the man called The Giver. In South Africa, they had created this set, and the bookcases went up — I’m not good at measuring in feet, but the entire room was bookcases, filled with bookcases. And they had gone to used bookstores in Cape Town and bought 22,000 books. And it was just magnificent. I loved The Giver’s quarters. And I wanted to go back and rewrite the description in the book.

But another thing they did that, I think, was better than the book was able to do was when the boy in the book had visions of things. I could only describe them, and they could show them. And there was one moment in the book, when the boy is about to leave, The Giver attempts to give him memories of … I think he calls it “of courage and of strength.” And he places his hands on the boy. In the movie, they show a sequence of things, and one is the young man standing in front of the tank in Tiananmen Square. And one is Nelson Mandela. I remember, watching the movie, I got choked up by that particular sequence. And one is just of a child dancing in the rain or in a sprinkler or something. I think it was, visually, so much better than words could portray those things.

However, having said that, I will say that I regretted — I understand why a movie has to do it. A book goes into the head of the main character, usually. And the reader and the author can, together, know what that person is thinking and experiencing. The movie can’t do this. A movie has to create action. And so I regretted the car chase in the movie. There’s no car chase in the book, but a movie seems to have to have one.

Chapter 16: I don’t recall that. I might have blocked it from my memory.

Lowry: And good for you!

They did a good job on a lot of things. And they were nice to include me.

As for The Willoughbys, they have not included me. And it is to be an animated film. I’ve just seen pictures and brief clips of the characters in it. In the book, they are human beings. In the animated film, I guess they are human beings, but they seem to be kind of elastic with long pointed noses. So, I don’t know what that portends.

Chapter 16: Is it going to be a Netflix film or a Netflix animated series?

Lowry: It’s a Netflix film. And I don’t know how this works. Sometimes films, like The Irishman, first appear on Netflix and then they appear in movie theaters. So, I don’t know whether this will or not.

But I will say this, which is just kind of interesting and may prove to be amusing: Because of the film coming out, the publisher suggested that I write a sequel to The Willoughbys, and I did so. And that book will be published in the fall. And it was great fun to go back to that family, because I’d enjoyed doing the first book and I loved doing the second. However, I have a feeling that the movie is going to conclude in a way that will not be connected to what happens in the second book. And, you know, readers and moviegoers will just have to accept that.

At the end of the first book, the very bad parents are frozen solid on an Alp — frozen with smiles on their faces, and they look like popsicles. But they’re up there on an Alp, unreachable. In figuring out how to deal with the family a second time, I made it 30 years later and global warming has begun to melt the Alps. The parents thaw out and emerge, but they are still the age they were at which they were frozen, which means that they are younger than their children. So, that was kind of a good starting point because it just presented the opportunity for a lot of problems.

Chapter 16: And that will be out in the fall?

Lowry: Yes. September, I think, is the publication date.

Chapter 16: Well, I’m going to ask you one more question that is very broad. So, you have the right to say, “I’ll pass on that one.” You’ve been in the field of children’s literature for decades. What are some ways — or maybe just one way — that you feel like it has evolved for the better?

Lowry: Oh, well, thank you for making it for the better. I can think of some ways in which it’s evolved in the other direction.

My first book was published in 1977, and so again, I’m not going to do the math quickly, but it was a really long time ago. Oh, okay, I can do the math, because I was 40 at that time, and now I’m 83. So, it was 43 years ago, my first book. And what I’ve seen since then, over the years, gradually, is the evolution of excitement over children’s books. The number of them is way more than it was when I published my first book. And the attention given to them — and even coming from children. It just seems to have exploded and magnified, and that can only be a good thing. I’m sure that with the increase in the numbers of books, probably there’s been a huge increase in the number of bad books.

Chapter 16: Right. Lots of mediocre ones.

Lowry: I mean, that’s the way the world works. Just the fact that it used to be a kind of small niche in the world of publishing and libraries. I remember, as a child, the children’s section of my small-town library was just a miniscule couple of shelves, surrounded by stuff for the big people. And now, of course, there’s an explosion of wonderful children’s sections in libraries. I’ve visited so many of them. And that, I think, is a wonderful thing.

Chapter 16: And you will see adults reading something like The Giver on the subway!

Lowry: That’s right. Yes. That took me by surprise, and that happened almost immediately when The Giver was published. It acquired an adult audience. I knew that because I began to hear from them. And I don’t know how that happened, but it can only be a good thing when a book connects generations. I’ve heard from so many people who say that they’re read this book and talked about it with their grandchild. And I think that’s a wonderful thing to have happen.

Julie Danielson, co-author of Wild Things! Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature, writes about picture books for Kirkus Reviews, BookPage, and The Horn Book. She lives in Murfreesboro and blogs at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast.