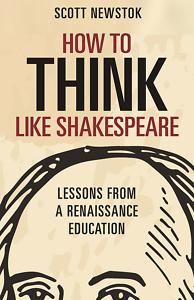

Be Like the Bard

Scott Newstok critiques modern education in How to Think Like Shakespeare

It’s unsettling in April 2020 to read a book that describes distance learning as a pallid substitute for classroom attendance and claims our phones and laptops deprive us of our attention spans while fostering social alienation. Yet these and other assertions pepper the pages of How to Think Like Shakespeare, Rhodes College professor Scott Newstok’s pithy diatribe about the honing of the modern creative mind.

Of course, Newstok had no way of knowing that his book would be published at a time when coronavirus makes distance learners of us all. Still, when he writes that “anxiety about education suffuses our moment,” we can’t disagree — he’s right. In this moment when teaching and learning methods are by necessity restricted, Newstok’s fascinating polemic is easier to read and appreciate if one takes it as it a description, rather than a prescription. As a concise history of Western pedagogical development, How To Think Like Shakespeare succeeds beautifully.

Shakespeare himself is only a touchstone. What Newstok wants is to describe the process by which Shakespeare (and others) learned to think like the geniuses they grew up to be. This leads him to ponder the ways in which aspiring intellectuals were, once upon a time, taught — and how their educations compare to pedagogical methods today. Invariably, he concludes that the old ways are vastly superior to the new.

“Thinking like Shakespeare untangles a host of today’s confused — let’s be blunt, just plain wrong — educational binaries,” he laments in the prologue. “We now act as if work precludes play; imitation impedes creativity; tradition stifles autonomy; constraint limits innovation; discipline somehow contradicts freedom, engagement with what is past and foreign occludes what is present and native.” Newstok himself is not convinced. “I stand with the contrarian view that to be a political progressive, one needs to be an educational conservative.”

That educational methods are culturally (and politically) determined is hardly a groundbreaking notion. Newstok knows this: “Little that I say here is new,” he admits. Still, it’s interesting to be reminded of all the ways pedagogical ideals — as well as the hallmarks of an educated human being — have shifted over time. And who among us doesn’t benefit from having her intellectual blind spots probed, questioned, and revealed?

That educational methods are culturally (and politically) determined is hardly a groundbreaking notion. Newstok knows this: “Little that I say here is new,” he admits. Still, it’s interesting to be reminded of all the ways pedagogical ideals — as well as the hallmarks of an educated human being — have shifted over time. And who among us doesn’t benefit from having her intellectual blind spots probed, questioned, and revealed?

The book consists of 14 short, quotation-stuffed chapters (“Of Thinking,” “Of Ends,” “Of Craft,” and so on). Newstok’s style takes getting used to — so numerous are his quotations (presented, often, in italics, which can be jarring) that the reader, yanked from one source to another and then another, may suffer a touch of mental whiplash. As we persist, however, chapters that felt at first like grab bags of random examples begin to reflect, refract, and strengthen one another. Gradually, quotes and observations accrue to enlightening effect.

“Of Imitation,” in which Newstok discusses the ancient and early modern affinity for copying one’s artistic “masters,” is the book’s strongest chapter. Copyright laws, he reminds us, were not invented until the 18th century; before that time, emulation of one’s talented predecessors was universally viewed as a valuable path toward finding one’s own creative way. It was not then, he insists, nor should it now be a sin to mimic one’s intellectual heroes. This flies in the face of modern educational mores. For present-day scholars, plagiarism is the ultimate offense and will get you kicked out of college faster than you can say, “Man is a mimetic animal.”

But Newstok insists that imitation is the best way for creatives of all types to wrestle with their artistic heritage. “‘Imitation’ sounds pejorative to us, a fake, a knockoff, a mere copy; at best, derivative drudge work,” he remarks. Consequently, and to our detriment, we have ceased engaging in “the still-valid practices of emulation (and repetition, and memorization), which are purported to quash independent thought.”

Newstok argues that just as play can nurture work, emulation and memorization can foment and encourage independent, original, brilliant patterns of thought. “We think through inherited forms,” he asserts, before reminding us that “James Wright typed out Rilke’s German sonnets, to better hear their music; Hunter S. Thompson did the same with Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Faulkner to feel what it feels like to write that well.” The list goes on: Abraham Lincoln memorized Aesop. A teenaged Judd Apatow “transcribed dialogue from taped episodes of Saturday Night Live” in order to internalize perfect comedic timing.

“Gwendolyn Brooks imitated Eliot, who imitated Pope, who imitated Milton, who imitated Spenser, who imitated Chaucer, who imitated Dante, who imitated Virgil, who imitated Homer, who consolidated centuries of oral transmission,” Newstok concludes, sounding rather triumphant. By the end of How To Think Like Shakespeare, he has us thoroughly convinced. To think and create effectively requires one to train and practice. By apprenticing ourselves to the past, we can ourselves become links in the glorious chain of human intellectual achievement.

From 2012 to 2016, Fernanda Moore was the fiction critic for Commentary. Her work has also appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Marie Claire, New York, and Southern Living, among others.