The Musicians You Didn’t Know You Knew

Revelations about Nashville’s uncredited session musicians

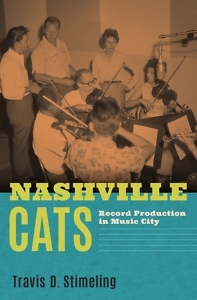

Travis Stimeling’s Nashville Cats: Record Production in Music City focuses on musicians you have likely heard many times but whose names you likely haven’t. Drawing from recent oral histories and archival material, Stimeling chronicles their lives and contributions to what came to be known as the Nashville Sound in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

As Stimeling reports, the Nashville Sound came about in response to the success of rock and roll. It was “a deliberate effort to try to engage rural-to-urban migrants with a more modern country music sound by blending adult lyrical themes with pop instrumental accompaniments.” Consequently, string arrangements, backing vocals, piano, and to some extent drum kits (rather than, for example, the traditional percussive bass or banjo strumming) all became part of mainstream country recordings.

Among the primary contributors to this new sound were the largely uncredited session musicians, the most predominant of whom have come to be known as the “Nashville A Team.” The volume of recordings these session musicians made staggers the imagination. Many of the A Team appeared on as many as 80,000 individual recordings during their careers. Stimeling writes that “even the most passive consumers of popular music have heard the Nashville A Team at some point in their lives and maybe even formed deep emotional attachments to their work, without even knowing their names.”

Vocal groups, such as The Jordanaires and The Southern Gentlemen, often received credit or were billed with the leading artist they supported, such as Jim Reeves or Patsy Cline. Instrumental musicians, however, went largely uncredited, less an oversight than the norm in popular music recording at the time, both in Nashville and elsewhere.

Some of the A Team did gain a measure of fame, although often not for their appearance on some of the most popular tunes of the era. For example, Chet Atkins, whose notoriety as a picking guitarist preceded the Nashville Sound, is widely credited for producing the earliest examples of the form. Brothers Harold (guitar) and Owen (piano) Bradley became better known for their recording and production company than as musicians who performed on the recordings themselves. A few of the A Team were occasionally name-checked somewhat obscurely in the media — for instance, there’s a reference to pianist Hargus “Pig” Robbins in Robert Altman’s 1975 Academy Award-winning film, Nashville.

Stimeling aims to give these instrumentalists their due and debunk the myth of the Nashville session players’ lack of musical sophistication. He cites a 1964 Time magazine article describing Nashville sidemen as “a small seasoned corps whose musical prowess is more heart than art [with] few, lest it cramp their style, having had formal training.” Stimeling rebuts this notion by reviewing the backgrounds of a dozen musicians, uncovering a diverse group who taught at local universities, had received conservatory training, and/or had undergone decades of performance experience before their session careers.

Stimeling aims to give these instrumentalists their due and debunk the myth of the Nashville session players’ lack of musical sophistication. He cites a 1964 Time magazine article describing Nashville sidemen as “a small seasoned corps whose musical prowess is more heart than art [with] few, lest it cramp their style, having had formal training.” Stimeling rebuts this notion by reviewing the backgrounds of a dozen musicians, uncovering a diverse group who taught at local universities, had received conservatory training, and/or had undergone decades of performance experience before their session careers.

Contributing to the informal image of Nashville session musicians was their capacity, as distinguished from their counterparts in New York or Los Angeles, to master what Harold Bradley labeled “cold turkey” sessions. Rather than needing staff arrangers to develop the novel hooks for a popular hit, Nashville musicians would create such novelties on the spot during the session, without sheet music, thereby reducing expense and time. Stimeling concludes that, as a result, the “Nashville A Team might, therefore, be rightfully viewed as co-authors and co-composers of nearly every hit recording to come out of Nashville’s Music Row for a span of twenty years or more.”

Nashville Cats recounts how the city evolved from a minor recording destination before World War II to become the major music production center and home of country music that it is today. The depth of local musicianship and the Grand Ole Opry, which radio had established as a nationally recognized platform, were well established before the war, but missing was music publishing interest. Existing Northern publishing companies, such as ASCAP, showed little interest in the market, which inhibited the income from penning popular tunes. Nashville also lacked a permanent recording studio. Both were addressed in the 40s, when Acuff-Rose Publishing, a collaboration of singer Roy Acuff and pop songwriter Fred Rose, was founded and Castle Recording Studio opened for business in the former Tulane Hotel. In the mid-50s, the Bradley brothers would also establish a studio, followed soon by RCA Victor, partly to address their newly secured contract with Elvis Presley.

Refreshingly, Nashville Cats devotes little attention to the famous names of country music, and the book doesn’t dwell on what Stimeling describes as the contributions of “the eccentric, the rare, and the exceptional.” Those credits are already firmly established. Stimeling turns our focus instead to the background figures, to the artists who have gone largely unrecognized but were equally important in creating what came to be known globally as Music City USA.

Jonathan Frey lives in Knoxville and writes about music and books.