The Resentment Game

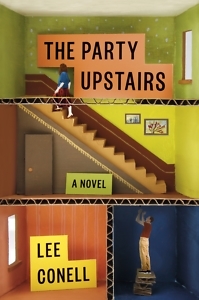

In Lee Conell’s The Party Upstairs, a father and daughter struggle to find their places in stratified Manhattan

Martin and Ruby, the father-daughter tandem at the center of Lee Conell’s debut novel, The Party Upstairs, live below ground level but don’t at first resemble literature’s famous basement dwellers. They’re not forgotten souls like Dostoevsky’s Underground Man, nor do they seethe at injustice like Ellison’s Invisible Man.

Martin, superintendent for the elegant apartment building on New York’s Upper West Side where he lives with his daughter, appears content to unclog drains and shoo away pigeons. College-educated Ruby, though struggling to start a career, seems well adjusted and good spirited. As the novel unfolds over the course of a single day, however, their façades crumble, and subterranean emotions explode to the surface.

As the day begins, Ruby feels rudderless, while Martin, after two decades of non-stop maintenance calls, is exhausted — but there’s cause for optimism. A former art history student with a lifelong love of dioramas, Ruby has an interview at the Museum of Natural History. The opportunity is made possible by Caroline, the trust fund princess of the building’s penthouse and Ruby’s oldest friend. Caroline gives Ruby life coaching with a breezy confidence that crosses the border into condescension, but Ruby will stomach the high-handedness, will even attend Caroline’s party that evening, if it means landing a dream job and thereby beginning to chip away at her mound of college debt.

Martin roots for his daughter’s success for reasons both loving and selfish: He knows that Ruby will not be happy until she has steady work and moves out of her childhood bedroom, preferably to a faraway town. “Her return to the basement felt to Martin like a failure not only for Ruby, but for himself,” Conell writes. Martin attempts to lower his blood pressure through meditation and bird watching, but what he really needs is an empty nest.

Conell, a graduate of Vanderbilt’s M.F.A. program in creative writing, inhabits her characters’ minds and skillfully charts their mental pilgrimages. The chapters alternate focus between Martin and Ruby, depicting their self-interrogations and flickering emotions with a nimble facility that recalls Virginia Woolf. Like Clarissa Dalloway in London, Ruby wanders in uptown New York, her memory attaching meaning to landmarks on each block. Conell follows Ruby and Martin through a wide range of moods, always circling back to the novel’s primary emotion: resentment.

Conell, a graduate of Vanderbilt’s M.F.A. program in creative writing, inhabits her characters’ minds and skillfully charts their mental pilgrimages. The chapters alternate focus between Martin and Ruby, depicting their self-interrogations and flickering emotions with a nimble facility that recalls Virginia Woolf. Like Clarissa Dalloway in London, Ruby wanders in uptown New York, her memory attaching meaning to landmarks on each block. Conell follows Ruby and Martin through a wide range of moods, always circling back to the novel’s primary emotion: resentment.

Living for so long beneath entitled residents, Martin and Ruby have become bitter. Ruby fixates on Caroline, in particular, for her pretentious marble sculptures of disposable products (paper plates, sporks). Ruby wants to support her friend’s art, but “it was difficult not to feel like it was unfair that Caroline was profiting off an artistic take on trash when Ruby was the one who had grown up right next to all that garbage.”

Caroline has the gall to horn in on Ruby’s preferred grievance. Walking in their neighborhood, they pass the time with an activity “Ruby had titled in her head the resentment game,” Conell writes. “The best way to really feel like legal adults seemed to be cataloging their childhood resentments toward their parents.” Caroline’s divorced parents, both narcissists, make easy targets, but when she prods Ruby about her own mother, who was often absent in Ruby’s childhood, Ruby finds resentment toward her mother “hard to excavate today, buried under those more vivid moments when Ruby had raged against her father.”

Father and daughter know their battles are pointless — Ruby wonders why she is “wasting all her energy on anger toward her father” — but neither knows how to break the pattern. Ruby resents Martin’s dirty fingernails and submissive attitude, reminders of the family’s inferior status. For his part, Martin had hoped when Ruby first moved out that she would begin to appreciate his commitment as a parent — a vain hope, it turns out: “Only now she was back, and things are just like before.”

Though Ruby is resentful, Conell does not portray her as wallowing in self-pity. When her ex-boyfriend remarks that “it must have been hard” living next to garbage when so much wealth resided over their heads, Ruby wishes she had “a solid upstairs/downstairs story … like she was some Dickensian dungeon-scrubber.” Ruby has seen too much poverty in New York, “inequities … deeper than anything she herself had experienced,” to indulge in personal melodrama.

The Party Upstairs, Conell’s follow-up to her remarkable story collection Subcortical, skirts the periphery of self-awareness, her characters experiencing moments of insight but struggling to achieve clear epiphanies. Paralyzed by self-consciousness, Ruby and Martin express themselves most authentically when they act on impulse, moments of sublimated violence and petty theft unleashing pent-up aggravation.

Perhaps the lesson at the heart of this sharp and affecting novel is that sometimes destruction, in moderation, can be creative. Ruby and Martin need to figure out how much to destroy, leaving enough room and wreckage for rebuilding.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.