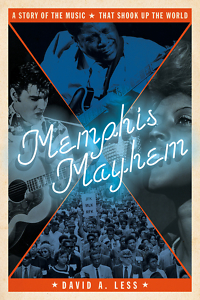

Putting the Music First

Memphis Mayhem is an insider’s history of the city’s sound

Ah, Memphis, the Southern capital of sin and song — “the old Delta synonym,” as Eudora Welty dubbed it, “for pleasure, trouble, and shame.”

The sin might have been as sinful somewhere else, but it’s the song that really made Memphis Memphis. No wonder so many writers have made it their subject, this city that changed the world through sound. Now comes David A. Less with Memphis Mayhem, a slim volume touted by its publisher, ECW Press of Canada, as the “definitive story of the birthplace of rock and roll.”

The sin might have been as sinful somewhere else, but it’s the song that really made Memphis Memphis. No wonder so many writers have made it their subject, this city that changed the world through sound. Now comes David A. Less with Memphis Mayhem, a slim volume touted by its publisher, ECW Press of Canada, as the “definitive story of the birthplace of rock and roll.”

Don’t worry — it’s not. There’s no more a definitive book on Memphis music than there is a definitive Memphis song (or sin). So we can just keep on reading and listening, partaking of the pleasures of each.

The chief pleasure of Memphis Mayhem lies in the serious care Less takes in telling this story of a city that set the world on its ear, time and time again, with blues, gospel, R&B, rockabilly, rock, soul, pop, and even jazz. That meticulous approach befits a third-generation Memphian who has spent his life around the city’s music, talking to those who made it and seeking to understand the forces and influences that shaped it.

Less takes us to the barrooms and nightclubs where drink and sometimes blood flowed, but he’s more interested, for example, in the underage kids who gathered in the parking lot outside the Plantation Inn, across the river in wide-open West Memphis, Arkansas, listening to the great Black bands inside through a metal speaker such as you’d find at a drive-in restaurant. “I would just go and sit and listen to the music,” songwriter and musician Don Nix told Less. “I didn’t dance or drink or anything else. I would just sit there and listen to that music.”

They weren’t just listening. They were learning.

Less takes us to school — literally — on the music of Memphis. He takes us to Manassas High in 1927, where future jazz legend Jimmie Lunceford, then a 25-year-old gym teacher, became the first band director at a Black city school. He started a student band called the Chickasaw Syncopators, which grew into the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra and would rival Cab Calloway and Count Basie in popularity. Less lingers over Booker Little Jr., a Manassas High product who was on his way to jazz greatness, playing with Eric Dolphy and others, but died at 23 from a blood disorder. And he takes us to Club Handy, “an after-hours stop for young hip musicians who wanted to test their skills against one another” at jam sessions and in cutting contests. The band leader at Club Handy was Bill Harvey, described by one regular as “something like the father of all of the musicians.” That regular was Willie Mitchell, who would go on, of course, to produce soul classics by Al Green and Ann Peebles at Memphis’ Hi Records.

Again and again, Less connects the dots. Or the notes, as it were.

A lifetime of living in Memphis, loving the music, revering those who made it, will do that. Even better if you make that music your life’s work — from research for the Smithsonian Institution and the National Endowment for the Humanities to a partnership in the Memphis International Records label. Less interviewed everyone from Memphis Slim to Steve Cropper, Dan Penn to Teenie Hodges. In the acknowledgments of Peter Guralnick’s 1986 classic Sweet Soul Music, the author thanks Less, “who freely offered up the fruits of his own extensive research as well as taking me out to Al Green’s Church of the Full Gospel Tabernacle for the first time.”

You’re in good hands, then, being taken to school by a guy who took Peter Guralnick to church. He’s lived the story he tells, although he only occasionally appears in it. At one point, he’s a 14-year-old boy at the Overton Park Shell, hanging out backstage with a friend, and meeting blues great Furry Lewis at the first Memphis Blues Festival in 1966 — “an eye-opener,” he writes, “for two kids from the all-white suburbs.”

You’re in good hands, then, being taken to school by a guy who took Peter Guralnick to church. He’s lived the story he tells, although he only occasionally appears in it. At one point, he’s a 14-year-old boy at the Overton Park Shell, hanging out backstage with a friend, and meeting blues great Furry Lewis at the first Memphis Blues Festival in 1966 — “an eye-opener,” he writes, “for two kids from the all-white suburbs.”

Later, in the mid-1980s, he’s the corporate director of entertainment for the Peabody Hotel — and still has that youthful enthusiasm for the Memphis sound in all its variations, as played this time by a jazz legend:

Like many luxury hotels, we had a lobby bar with a grand piano. I would sometimes receive a telephone call late at night from hotel security.

“Sorry to bother you so late, but Phineas Newborn Jr. is playing piano in the lobby and he won’t leave. What should we do?”

My response was always the same: “Just leave him alone and enjoy what he’s playing.”

You wouldn’t begrudge the author appearing a little more in his own book, but this less of Less is more approach seems perfectly in character. This isn’t about him. This is the story of Memphis, its music and musicians — and he tells it well, if without the flair and verve you’ll find elsewhere on the same subject.

No, this isn’t the last word on Memphis music or the first book to read if you’re not already immersed. Hopefully I’m not telling you anything you don’t already know, but the canon includes Stanley Booth’s Rythm Oil, Preston Lauterbach’s Beale Street Dynasty, and most anything with Robert Gordon’s name on it.

Memphis Mayhem, though, is a worthy addition to the shelf because Less puts the music first. And then, from the parking lot of the Plantation Inn to the lobby bar of the Peabody Hotel, from the Black high school band rooms to Rev. Al Green’s church, he lets it ring out.

No sin in that.

David Wesley Williams is the author of the novel Long Gone Daddies (John F. Blair, Publisher, 2013), and his short fiction has appeared in Oxford American, Kenyon Review Online, and in Akashic Books’ Memphis Noir. He lives in Memphis.