Imagination and Wit, with a Side of Conscience

A brief look at Margaret Atwood’s remarkable body of work

When Margaret Atwood’s debut novel, The Edible Woman, appeared in the U.S. in 1970—it was published in Canada, her home country, the previous year—The New York Times review remarked on the author’s “wacky and sinister” imagination and on the subtlety of her “feminist black humor,” noting that “Miss Atwood’s comedy does not bare its teeth.” It was, in retrospect, a perceptive assessment of the young writer’s core sensibility. Those same qualities of inventiveness, deadpan wit, and a vigorous feminist consciousness can be found in the dozen novels Atwood has published since, from the brilliant postmodern puzzler The Blind Assassin to the dystopian fantasy The Year of the Flood. What the Times critic couldn’t have known was that Atwood’s deft writing and sharp insight, combined with a gift for surveying the world around her and imagining startling possible futures, would make her one of the most widely read and respected writers of her generation.

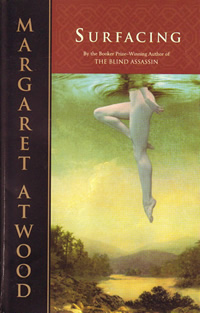

From the beginning Atwood put women’s experience at the center of her fiction. Well before discussion of eating disorders became standard media fare, The Edible Woman offered up a protagonist who responds to the sexual dilemmas of young womanhood by becoming unable to eat. Atwood’s follow-up novel, Surfacing, took the question of navigating life in a female body into wilder territory, both literally and figuratively, with an unnamed narrator who descends into a kind of elemental madness during a sojourn on the remote Canadian island where she grew up. The story addresses two recurrent, connected concerns in Atwood’s fiction: the suppression of a woman’s authentic self and the damaging effects of voracious consumer capitalism on both human beings and the environment. Near the end of the book, the narrator seems to be freed as she sees herself stripped of all the artifice of consumer society and conventional femininity, with her “face dirt-caked and streaked, skin grimed and scabby, hair like a frayed bathmat stuck with leaves and twigs. A new kind of centerfold.”

From the beginning Atwood put women’s experience at the center of her fiction. Well before discussion of eating disorders became standard media fare, The Edible Woman offered up a protagonist who responds to the sexual dilemmas of young womanhood by becoming unable to eat. Atwood’s follow-up novel, Surfacing, took the question of navigating life in a female body into wilder territory, both literally and figuratively, with an unnamed narrator who descends into a kind of elemental madness during a sojourn on the remote Canadian island where she grew up. The story addresses two recurrent, connected concerns in Atwood’s fiction: the suppression of a woman’s authentic self and the damaging effects of voracious consumer capitalism on both human beings and the environment. Near the end of the book, the narrator seems to be freed as she sees herself stripped of all the artifice of consumer society and conventional femininity, with her “face dirt-caked and streaked, skin grimed and scabby, hair like a frayed bathmat stuck with leaves and twigs. A new kind of centerfold.”

The success of The Edible Woman and Surfacing established Atwood’s reputation, and the books soon began showing up on women’s-studies syllabi, which no doubt boosted the readership for her subsequent efforts, including Lady Oracle and Bodily Harm. By the early 1980s Atwood had a solid following, especially among well-educated younger women who were an ideal audience for The Handmaid’s Tale when it appeared in 1985. Inspired by the rise of the religious right in the U.S., The Handmaid’s Tale depicts a dystopian society, the Republic of Gilead, ruled by religious extremism. Women are robbed of all autonomy and are compelled to take on assigned roles. The young and fertile become “handmaids”—breeders forced to submit to ritual sex with a member of the ruling elite.

The Handmaid’s Tale got a sniffy reception in some quarters. Mary McCarthy dismissed it as implausible, complaining that it was “powerless to scare” and had “no satiric bite.” The critical reception was friendlier in Britain, where it became the first of Atwood’s novels to be shortlisted for the prestigious Booker Prize. Regardless of what the critics had to say, The Handmaid’s Tale was embraced by readers—it’s the subject of this year’s Nashville Reads program—and remains Atwood’s best-known novel. Its vision of women reduced to faceless breeders and drudges, obliged to don color-coded habits that designate their status, has become an enduring trope in the popular imagination. Last spring, social-media chatter about the conservative “war on women” was peppered with references to the Republic of Gilead.

The Handmaid’s Tale got a sniffy reception in some quarters. Mary McCarthy dismissed it as implausible, complaining that it was “powerless to scare” and had “no satiric bite.” The critical reception was friendlier in Britain, where it became the first of Atwood’s novels to be shortlisted for the prestigious Booker Prize. Regardless of what the critics had to say, The Handmaid’s Tale was embraced by readers—it’s the subject of this year’s Nashville Reads program—and remains Atwood’s best-known novel. Its vision of women reduced to faceless breeders and drudges, obliged to don color-coded habits that designate their status, has become an enduring trope in the popular imagination. Last spring, social-media chatter about the conservative “war on women” was peppered with references to the Republic of Gilead.

If The Handmaid’s Tale is the most widely read of Atwood’s novels, The Blind Assassin, published in 2000, is the most lavishly honored. With its slippery, multi-layered narrative centered on the relationship between two sisters, The Blind Assassin was admired for offering both a rich story and what The Guardian called “a sophisticated meditation on the uses and perils of fiction.” The novel won the Booker Prize as well the Hammett Prize for crime fiction, and it was short-listed for the Orange Prize.

In recent novels, Atwood has returned to the realm of what she calls “speculative fiction,” with a trilogy set in a future world devastated by a bio-engineered plague. Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood (the third installment is due in 2013) take on Atwood’s usual concerns, but with a special emphasis on the dangers of arrogantly exploiting the natural world. In promoting The Year of the Flood Atwood married art to activism, turning her book tour into a “traveling medicine show” to promote environmental awareness. (She discussed the tour with Chapter 16 in a 2010 interview.)

Although she is best known for her novels, Atwood first gained notice for her poetry, through her 1964 debut collection, The Circle Game. She was still considered primarily a poet when Surfacing arrived—so much so that Paul Delaney, in his review for The New York Times, set Atwood’s book alongside Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar because both were “novels by poets.” Collections of new poetry have appeared regularly over the past four decades, most recently The Door in 2007, which Jay Parini praised for its “robust, clear language” and “ironic twang.” As in her prose, Atwood is witty and economical in her poems, and she has a fondness for killing sentiment with just the right absurd twist. In “Resurrecting the Dolls’ House,” for instance, the return to childhood takes an ugly turn:

Although she is best known for her novels, Atwood first gained notice for her poetry, through her 1964 debut collection, The Circle Game. She was still considered primarily a poet when Surfacing arrived—so much so that Paul Delaney, in his review for The New York Times, set Atwood’s book alongside Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar because both were “novels by poets.” Collections of new poetry have appeared regularly over the past four decades, most recently The Door in 2007, which Jay Parini praised for its “robust, clear language” and “ironic twang.” As in her prose, Atwood is witty and economical in her poems, and she has a fondness for killing sentiment with just the right absurd twist. In “Resurrecting the Dolls’ House,” for instance, the return to childhood takes an ugly turn:

all as it should be,

except for an extra, diminutive father

with suave spats and a mustache:

maybe a wicked uncle

who will creep around at night

and molest the children.

In addition to her novels and poems, Atwood has written short stories, children’s books, and several highly regarded nonfiction titles, most notably Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth, in 2008. Now in her early seventies, she is a lively figure on the cultural scene, with a highly popular presence on Twitter and a tendency to give wry interviews. And, of course, she continues to write at top form. She recently said that a person of her age “can afford to be undignified. You’re free to explore, and to guinea-pig yourself, and to stretch the boundaries.” Coming from an artist of Atwood’s brilliance and skill, those are promising words.

In connection with the receiving the 2012 Nashville Public Library Literary Award, Margaret Atwood will give a free public reading on October 27 at 10 a.m. in the auditorium of the Nashville Public Library downtown.