Reaching for Joy

Poet Toi Derricotte discusses isolation, community, and taking risks

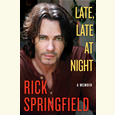

Toi Derricotte’s “I”: New and Selected Poems spans over four decades of work by a poet unparalleled in the tenderness and honesty with which she writes about the self, trauma, and memory. She unpacks race, gender, sexuality, class, violence, motherhood, and more, with rich detail and incantatory music. She explores and explodes poetic form, from pantoums to free-verse to genre-bending hybridity. A finalist for the 2019 National Book Award, “I” is part gift, part window, and part compass for all of us who love poetry.

I’m grateful for and fascinated by Derricotte’s work for so many reasons — and one word I keep coming back to is “holding.” In each of her previous collections — The Empress of the Death House, Natural Birth, Captivity, Tender, and The Undertaker’s Daughter — Derricotte wrote with searing clarity about the abuse and silencing she survived as a child and their lasting effects on her thinking and behavior as an adult. To read her new work is to marvel at her miraculous serenity, this holding, this evolved poetic consciousness. In “After all those years of fear and raging in my poems,” she writes:

I’m grateful for and fascinated by Derricotte’s work for so many reasons — and one word I keep coming back to is “holding.” In each of her previous collections — The Empress of the Death House, Natural Birth, Captivity, Tender, and The Undertaker’s Daughter — Derricotte wrote with searing clarity about the abuse and silencing she survived as a child and their lasting effects on her thinking and behavior as an adult. To read her new work is to marvel at her miraculous serenity, this holding, this evolved poetic consciousness. In “After all those years of fear and raging in my poems,” she writes:

It took so many years, the self

breaking like a pod, so many years

to pull up the details… to bring all that

to consciousness, to hold that pain

until it writes a poem, to hold it

for years until you learn both

the holding and the writing …

Derricotte’s poems invite us to find gentler pathways toward our inner lives: how to hold a painful memory, without judgment or bitterness, in all its context and complexity; how to exist in the present moment as our fullest and most embodied selves. A healing balm as we approach the end of a profoundly difficult year, her poems teach us that softening, too, can be an act of resistance.

A professor emerita at the University of Pittsburgh and a former chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, Derricotte is the recipient of the 2020 Frost Medal for distinguished lifetime achievement in poetry from the Poetry Society of America. Her literary memoir, The Black Notebooks, received the 1998 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Nonfiction. With poet Cornelius Eady, she co-founded the Cave Canem Foundation in 1996, which received the National Book Foundation’s 2016 Literarian Award for Outstanding Service to the American Literary Community.

Derricotte answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: I want to start by asking about your latest book, “I”: New and Selected Poems. How did that process of assembling poems compare to arranging a single collection?

Chapter 16: I want to start by asking about your latest book, “I”: New and Selected Poems. How did that process of assembling poems compare to arranging a single collection?

Toi Derricotte: I usually spend years assembling a book. The Black Notebooks took 25. I usually spend about seven to nine years between books. I write poems over time — three or four years — and, after a while, I have an idea about what I’ve been writing about. That’s when a book starts to take shape.

There were only two books in which I knew my subject: The Black Notebooks and the book about my son’s birth in a home for unwed mothers, Natural Birth. Both books took many years to write. Actually, I didn’t start the book about my son’s birth until he was 17 years old. He didn’t know he had been born in a home for unwed mothers! So, you can see there are many processes at work when you write and publish books. Not only about poetry, but about your life. My life and my work change after I finish every book.

“I” was the easiest book I ever put together. I just went through all my books and chose the only poems that I love and put all the new poems in alphabetical order. It took about a week.

Chapter 16: At times throughout the years, your work has been called “confessional.” How do you feel about that label, and how might you describe its place now in contemporary U.S. poetry?

Derricotte: I don’t care too much about what I’m called. I’m glad when people talk about my work. I’m glad when anyone can relate to my work, and I’m thrilled if they say they learned something about themselves because of what I’ve written. I’m probably most happy if my work helps a poet write a poem. I think I’m mainly talking to other poets when I write. I love other poets. I think most of them are people that I could be friends with. It’s not like that in the other world. It took me so many years of loneliness until I found poets.

Chapter 16: While researching you and your work, I came across the YouTube series you recorded earlier this year with the Beinecke Library at Yale, Creativity in Isolation —it felt like such a gift, that intimate peek into your creative process.

Derricotte: Glad you liked my YouTube videos. That really opened me up, got me talking in an easier way than I have in the past in formal settings. They wanted me to do a lecture thing, and I knew if I did that, I’d write something that had to sound smart and, when I gave it, I’d be uptight. Now I just want to be myself when I speak, and I know that I’m more alive when I’m doing something a little on the edge, when I don’t know what’s coming next. That’s the way I used to teach kids when I taught in the Poets-in-the-School Program. It’s a risk to put yourself out there, but that’s when the light shines and something new comes through. More and more I’m trusting the creative process in many ways, not just writing.

Chapter 16: On the subject of creativity in isolation, how has isolation today, related to the COVID-19 pandemic, impacted you and your work?

Chapter 16: On the subject of creativity in isolation, how has isolation today, related to the COVID-19 pandemic, impacted you and your work?

Derricotte: I love isolation. Always have. I wonder what’s going to happen to “society” as we grow accustomed to it. Now, I think so much running around was unnecessary, like a chicken with its head cut off. (Oh, that’s so bloody and also, haha, cliché! I don’t know which is worse!) But, seriously, where were we going? I like to cook for myself. I write more. I exercise. I read. I think. I used to watch the news, but it makes me crazier! I’m living like people when they used to live 50 miles apart.

But I’m very worried about what’s going to happen to the economy, and especially the lives of people who have to work outside of their homes. We’re in a scary time, and I’m always aware of that.

Chapter 16: Cave Canem catalyzed huge changes in the landscape of U.S. literature, having inspired and laid the groundwork for similar organizations like Kundiman, CantoMundo, and Kimbilio to flourish. What advice do you have for poets trying to organize similar relationships or safe havens of creativity in their own local communities?

Derricotte: It was very important that Cave Canem began as a partnership between Cornelius and me. There never was a “head.” It’s based on the idea of a circle, of everyone being equally important. It’s about conversation, about being able to say and think whatever you need to in order to do your work. I think people of color — especially right now, when there is so much to fear and grieve — need to have a friend, someone they can really talk to, and especially to talk to about what’s happening to people of color, about writing. Even if they aren’t writing now. Some of us are so grief-stricken, so wounded by what’s going on, we’re not able to write. But poets need other poets. I’m part of a little group of CC fellows that a Cave Canem elder started, Afaa Weaver, and we try to talk via Zoom on Saturday mornings. It’s a small group, but it means so much to me to see those other Black poets. Just seeing their faces makes me grateful. And when they talk, I can feel the beginnings of so many poems that they are going to write.

I’d say to anyone who wants to begin a society of writers: Reach out. It takes guts, energy, belief in yourself to reach out. Look for someone who can support you. Support another poet! Take good care of your loving heart.

Chapter 16: Like so many others, I love the line “joy is an act of resistance.” It rings especially true today. Where are you finding joy these days?

Derricotte: I find joy in reaching out to others. In the morning I try to do something for someone else, or at least to be in touch with someone I love. Do something little for someone else. Reach out each day. It is joyful to feel connected. But first you have to connect with yourself!

Maria Isabelle Carlos is a poet in the M.F.A. program at Vanderbilt University. Winner of the Penelope Niven Creative Nonfiction Award from the Center for Women Writers 2020 International Literary Awards, nominee for a Pushcart Prize, Best New Poets, and Best of the Net, she resides in Nashville.