The Collateral Consequences of Hubris

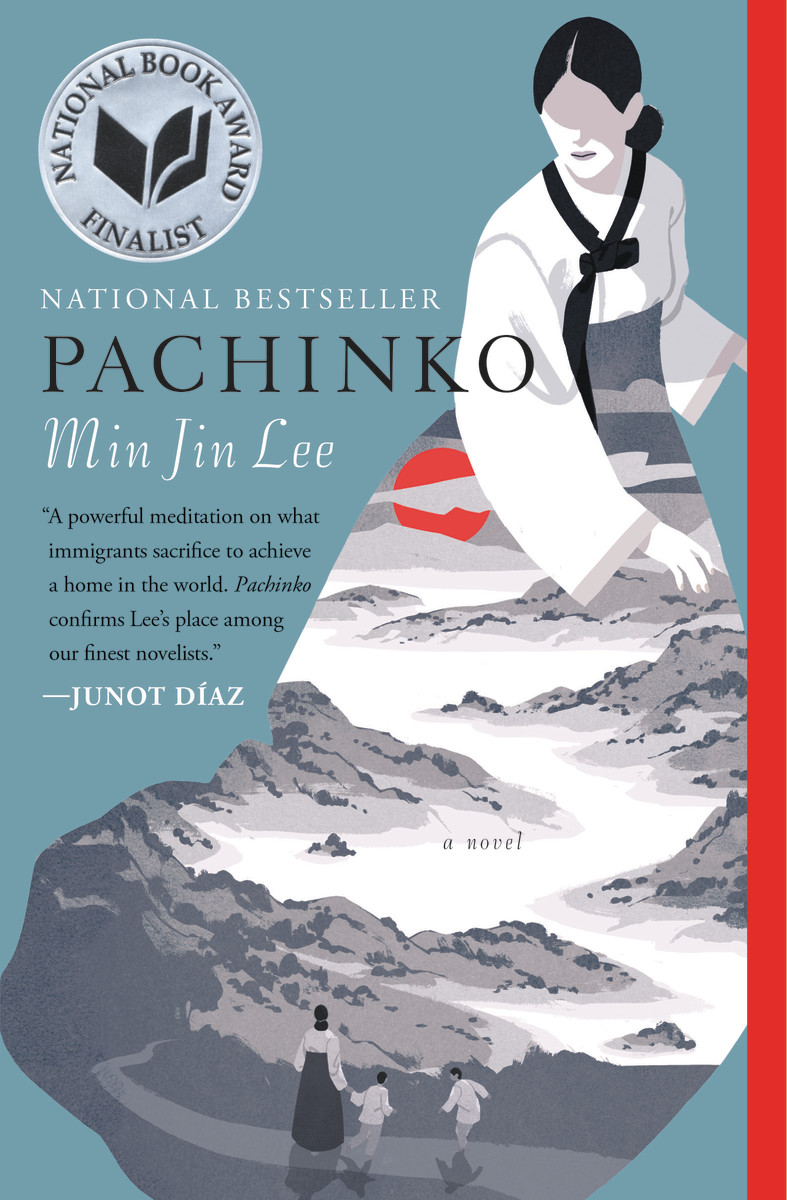

Ed Tarkington talks about the class conflicts at the heart of his second novel, The Fortunate Ones

Midway through Ed Tarkington’s novel The Fortunate Ones is a telling exchange between Vanessa, a 20-something product of new Nashville wealth, and Charlie, the outsider artist who has loved her for years. After shattering him with news of her engagement, Vanessa goes on to correct Charlie’s use of “congratulations,” noting that “best wishes” is the polite phrase reserved for the bride-to-be.

This gilded little knock relays the novel’s class tectonics. The story centers on Charlie, Vanessa, her blueblood fiancée Archer, and a community shaped by its relationship to an elite prep school, Yeatman. We follow Charlie’s scholarship-fed enrollment in the ‘80s and meet the patron network that elevates him and his mother from low-rent apartment life to tony Belle Meade society. Decades after graduation, Yeatman will pull everyone’s orbit in the political space, whether candidate or backer, community activist or — in Vanessa’s case — veneered wife. The Southern sense of tragedy adds to the Gatsby-esque tale, as does the transformation of contemporary Nashville itself.

These characters are as morally chipped as anyone, and they yearn to live beyond the boundaries of status. Yet theirs is a caste in which even tidbit manners — arbitrary if not insidious inventions, after all — still mark one’s identity. To that end, “best wishes” symbolizes a towering class wall and the efforts to scale or demolish it.

Given that Tarkington and I tell about the South in different ways (full disclosure: he reviewed my novel for Chapter 16), I was excited to ask him about The Fortunate Ones. He answered questions for Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: In writing this novel, you have lived and breathed every character, scene, and sentence for some time, telling a story that spans decades. Here’s the author’s challenge: Can you describe The Fortunate Ones in a sentence?

Ed Tarkington: Long version: It’s about the collateral consequences of great hubris, the limitations of perspective, the love-hate relationship between the have-nots and the haves, the often-destructive allure of wealth, and the perils of noblesse oblige. Short version: It’s a cross between The Great Gatsby, Brideshead Revisited, and All the King’s Men.

Chapter 16: What makes Nashville a distinct setting? What was it like to write about the place you call home?

Tarkington: I initially chose to write about Nashville because I love it, and because its representation in other media strikes me as being largely shallow and inaccurate, and I wanted to correct or broaden that understanding somewhat. But at the outset, the choice felt pretty circumstantial. I thought the story I had to tell could just as well have been set in Atlanta or Birmingham or even outside the South. Looking at it now, however, I feel as if Nashville became a character in the novel — perhaps the main character.

It’s hard to think of an American city which has undergone such dramatic growth and change at such a rapid pace from the last decade of the 20th century to the present moment. And while the characters and situations in The Fortunate Ones live and occur in many contexts, Nashville seems to me perhaps the best, if not the only, place to explore their conflicts and contradictions. Nashville’s exponential growth has exacerbated an ongoing identity crisis, one that really came into focus for me during the 2015 mayoral election, which became unusually divisive for an office that’s supposed to be nonpartisan. Mayoral contests are usually tame affairs, but the 2015 runoff pitted a charismatic, progressive transplant against a genteel, conservative Nashville native. It felt less like a choice over who had the best plan to fix the traffic than between the New South and the Old, with all the baggage those two concepts carry, and it got surprisingly nasty, especially given that both candidates came across publicly as genuinely polite, amiable, decent people.

Given the bitter polarization that has become the central narrative of American life since 2016, Nashville now seems like the perfect place to explore the conflicts and contradictions that were gnawing at me when I decided to write a book about how we got to this point, and how good people can end up going to dark places when the stakes get high and they come to believe that the ends justify the means.

Chapter 16: Charlie, Archer, Vanessa, and other characters are driven and defined by class status and love. How do the expectations of the former dictate the boundaries of the latter?

Chapter 16: Charlie, Archer, Vanessa, and other characters are driven and defined by class status and love. How do the expectations of the former dictate the boundaries of the latter?

Tarkington: Archer, Vanessa, and Charlie clearly occupy three distinct positions across the class/wealth spectrum. Archer was born into privilege, and his parents, especially his mother, have an old money pedigree. Vanessa’s family is extravagantly wealthy, but her parents are new money, rich enough to buy their way into the high society world but still a little dubious, and quietly resented by the more genteel old guard. Charlie is the poor outsider, and he’s an artist, which makes him both sensitive to things other people might not notice and also a great lover of beauty, easily enamored by the trappings of wealth in an increasingly aesthetic rather than purely materialistic way.

Arch takes his status for granted, but his father’s failures engender in him a deep drive to be perceived as an archetypal Southern alpha male. Perhaps because his charisma makes him the type of person who has never lacked attention, love is a bit of an afterthought to him. Ambition is his drug of choice. Vanessa, on the other hand, feels this obligation to sort of legitimize her family by having perfect manners, attending an Ivy League college and law school, and marrying a guy like Arch. She doesn’t realize until much too late that she might have followed her own path and pursued her own fulfillment.

Charlie falls in love with the image people like Arch and Vanessa embody and allows his sense of self-worth to be tied to their attentions and affections. He buys into the notion of their exceptionalism and cannot imagine himself happy outside of their world, even if he can never truly be one of them. I think this is really the source of his bitterness at the outset of the novel. The story he has to tell is the process by which he finally achieves self-awareness and a sense of self-acceptance and, I hope, something approaching redemption or even grace.

Chapter 16: How does this novel address, complicate, and/or critique the “Southern way of life,” a phrase taught to Charlie and the others from adolescence?

Tarkington: The deconstruction and demolition of so many of the myths about Southern culture and identity have been ongoing in literature for a long time but seem to have accelerated in the public consciousness at a stunning rate in the years since I started writing The Fortunate Ones. Perhaps the most troubling epiphany for white Southerners has been the widespread acknowledgment of the degree to which our culture continues to be influenced by white supremacy. This is a hard truth to swallow for basically decent, fair-minded people who have grown up unconscious of the extent to which they have historically benefitted and continue to benefit from a status quo foundationally rooted in a moral evil, one which still infects so many of us through our inherited biases. It really is an experience of grief, processed according to the Kübler-Ross model: denial, anger, bargaining/rationalization, depression, and, finally, acceptance.

Part of my goal with The Fortunate Ones was to show how boys like the one I once was get indoctrinated into the myth of “the Southern way of life”— or, perhaps worse, how they might consciously abandon their principles and tolerate or even participate in things they know are just plain wrong for something as fleeting and trivial as social acceptance, or a good time, or the affection of a charismatic friend or a beautiful girl. Willful ignorance in the name of self-interest: Perhaps this, more than anything else, as much as it pains me to say it, is the legacy of the “Southern way of life.” I identify with Quentin Compson — “I don’t hate it! I don’t hate it!” But I want to be honest about it and about and with myself. Southern pride is a sort of addiction, and the first step toward recovery is acknowledging that you have a problem.

Chapter 16: One major storyline follows Archer’s ascension into national politics. Was it difficult to turn politics into plot at a time when the subject carries such tremendous baggage?

Tarkington: Much has been made recently of the fact that political polarization has exposed the extent to which we are living in two Americas, functioning according to two fundamentally different perceptions of reality. Early on, I realized that my story was really about two distinct worlds — alternate realities, if you will. My narrator, Charlie, passes from one world into the other and learns its secrets but is also seduced by it, at least for a while. Arch inhabits that other world and is aware of its contradictions. But rather than trying to change the status quo or simply walk away from it, he exploits his insight for personal advantage and ultimately pays a terrible price for his hubris.

I started this book long before Trump was elected. Honestly, if I’d seen it coming, I’d probably have written another book. A few years ago, real-life politics felt too surreal for realistic fiction about politics to be of any use. But now, I feel like this book has turned out to be much more pointed and relevant than I imagined, even before the ascendance of Trump. A novel which traces the evolution of a charismatic businessman who jumps into politics and rises to power through sheer force of charm, boundless entitlement, and a ruthless conviction that the ends justify the means — that story feels right on time.

Still, this book was scary to write and scarier to publish. Explaining how he’d decided to write The Underground Railroad, Colson Whitehead said, “The one that scares you shitless is the one you should do.” I hope he was right.

Chapter 16: You teach at an institution that must inform the fictional boys’ school, Yeatman. What would you tell students — or any apprentice writer — about the balance of truth and fiction? How do you render drama from the everyday?

Tarkington: It would be absurd to pretend that the fictional Yeatman School is not modeled on Montgomery Bell Academy, where I’ve taught for nearly 14 years. As the old adage goes, “Write what you know.” It is worth noting, however, that the Yeatman half of the novel occurs in the 1980s, long before I’d ever even heard of MBA or set foot in Nashville. With the exception of one character who serves as a reverent homage to a legendary retired colleague, not a single character or incident in The Fortunate Ones is based on anything or anyone associated with MBA. What the novel owes to MBA is an understanding of the culture, rituals, and day-to-day business of a prep school for boys. The characters and conflicts are either entirely imagined or based on people I met in other settings and things I observed in or heard about from them. The MBA I know is a far more progressive and enlightened place than the school I imagined for The Fortunate Ones—imperfect, but always evolving and striving to be better, in all the right ways. I am proud to work there and exceedingly proud of my students, several of whom are now my colleagues and a few of whom I consider dear friends.

When I talk to my students about the art of fiction, I come back again and again to what Tim O’Brien wrote in the “Good Form” chapter of The Things They Carried about the difference between “story truth” and “happening truth.” Or what Ken Kesey writes at the end of the first chapter of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest: “It’s the truth, even if it didn’t happen.” Or what I heard Ann Patchett say her mother tells people when they ask her how much of what occurs in Commonwealth really happened: “None of it happened, and all of it’s true.”

I believe my task — my aim, my reason for writing — is to tell the truth about the things that keep me up at night in a manner that will make the reader feel what I felt. Sometimes, the facts aren’t strong enough. Sometimes, the truth has to be toned down to be plausible as fiction, or at least to prevent sensationalism from obscuring or overtaking the depth of emotion or introspection I’m hoping to arouse or invoke. To me, the novel is a mirror. It doesn’t teach us about the world; it reveals to us what we already know but were unable to articulate for ourselves. Hence, it doesn’t have to be real to be true; it just needs to feel real.

Chapter 16: Did the process of writing this novel differ from that of your first book, Only Love Can Break Your Heart? Was it easier, and/or were there new challenges?

Tarkington: When I started writing Only Love Can Break Your Heart, I was writing mostly for myself. The Fortunate Ones was under contract before I’d really begun to write it. So instead of just writing for myself, I was writing for my agent, my editor, and all the people who had read and enjoyed Only Love Can Break Your Heart. Then, literally the day I mailed the signed contract for The Fortunate Ones to my agent, my wonderful editor, Andra Miller — who had given me my big break and taught me everything I know about how a book goes from messy manuscript to bookstore shelves — called to tell me she was leaving Algonquin to become an executive editor at Ballantine. The project eventually ended up on the desk of Kathy Pories, who has edited quite a few of my literary idols. I’d met Kathy before, and we’d hit it off, I thought, and I’d read and loved at least half a dozen books she edited, but I was really anxious about how she would feel about working with me. We set up a time to talk, and the conversation lasted for more than two hours. I already admired Kathy, but by the end of that conversation, I trusted her, completely.

The Fortunate Ones was a much more ambitious project than Only Love Can Break Your Heart, and I was just getting started, so from the very beginning, I really craved and fed off of Kathy’s guidance and encouragement. After I’d finished the first draft, Kathy read it, and we met up here in Nashville and spent several hours talking through what was working and what wasn’t and sort of storyboarded a pretty radical revision. The work was incredibly challenging, but Kathy gave me the direction and the confidence to produce a book of which I am now very proud. She’s such a lovely person that she’d never take the credit she deserves, but I am here to tell you, Kathy Pories is special — the kind of editor who isn’t supposed to exist anymore.

Chapter 16: What is the state of storytelling in the South? What dynamics are constant or changing?

Tarkington: To me, Southern writing isn’t really so much about setting as it is about the music of Southern language: the slow cadence, the lyricism, the juxtaposition of genteel, elevated diction and the alliterative rhythm of the rural voice that is at once homespun and Homeric. This is why someone like, say, Richard Ford can write about New Jersey or Montana or Ireland and still be writing what I consider Southern stories and novels. It’s the same reason that Colum McCann can write about New York and still be writing what are essentially Irish stories and novels. Ireland and the American South are much alike in the distinct musicality of their language idioms.

Regarding Southern culture or subject matter: As the South goes, so goes the nation. Walker Percy is a great hero of mine. One of my favorite Percy anecdotes is the story about his Today show appearance after he won the National Book Award for The Moviegoer. When rather condescendingly asked why the South produces so much great literature, Dr. Percy tersely replied, “Because we lost the war.” What Dr. Percy may not have understood then as he might today was that the real war never ended, and now, it has no armies or battle lines. Perhaps it never did.

Today, I think, stories set in the South should be recognized not as stories about a particular place and time, but as microcosms of the great crucible in which all Americans now labor in our ongoing struggle over the future of our country’s divided soul. Those stories can be chastening and ominous, but they can also be hopeful. And for my part, I choose hope. I’m thinking now of what the great John Lewis said in a conversation with our friend Margaret Renkl in November 2016: “You have to be hopeful. You have to be optimistic. If you lose that sense of hope, then it’s like not existing at all.”

[This interview originally appeared on January 4, 2021.]

Odie Lindsey is the author of the story collection We Come to Our Senses and the novel Some Go Home, both from W.W. Norton. He is writer-in-residence at the Center for Medicine, Health, and Society at Vanderbilt University.