Poor, Forked Animals

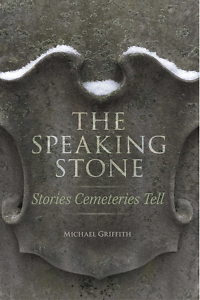

In The Speaking Stone, Michael Griffith considers the contingent nature of existence

Michael Griffith humbly remarks that his books do not qualify him as a “World Historical Individual,” yet in The Speaking Stone: Stories Cemeteries Tell, he accomplishes a feat that none of the politicians, industrialists, and artists he portrays could pull off: He brings the dead back to life.

The book’s conceit appears modest — to record the lives of people interred in Cincinnati’s Spring Grove Cemetery and Arboretum — but its impact is profound. These essays track the subtle ways history intersects with individuals, and they remind us that pride and ambition lead inexorably to oblivion. Griffith simultaneously sharpens our sympathy for solitary lives and chastens us for harboring fantasies of immortality.

The book’s conceit appears modest — to record the lives of people interred in Cincinnati’s Spring Grove Cemetery and Arboretum — but its impact is profound. These essays track the subtle ways history intersects with individuals, and they remind us that pride and ambition lead inexorably to oblivion. Griffith simultaneously sharpens our sympathy for solitary lives and chastens us for harboring fantasies of immortality.

Gravestones themselves, Griffith observes, “represent an attempt — conscious or not, self-ironizing or not — to claim for ourselves a limited permanence.” Very limited, as the author points out: “What vanity is more pitiful — or more poignant and inevitable — than the one that moves us to try, and fail, to dictate the terms we’re remembered by.”

Among the most colorful of the characters in The Speaking Stone is Fanny Wright, a Scots woman born in 1795 who at a young age “fell under the spell of American ideals of liberty.” After becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen, she devoted her life to civil rights, publicly advocating for the abolition of slavery and for women’s suffrage. Wright attempted to put her ideals into practice by establishing a utopian community on 2,000 wooded acres east of Memphis (where the suburb Germantown now lies).

Though the community (named Nashoba, “a Chickasaw word for wolf”) failed to achieve its emancipatory goals, Wright’s oratory prowess and striking figure (tall, red haired), turned her into a polarizing public figure. Griffith connects her story to contemporary concerns regarding the paradoxical nature of fame and “the prison-house of celebrity,” as he puts it. “To be known by the public,” he notes, “is to be owned by it. If Britney Spears earns a PhD in astrophysics, it will enter her obituary only after the crotch-shot caught on film by a paparazzo.”

This collection is replete with pop-cultural references that will appeal to Griffith’s fellow Gen X readers. Smokey and the Bandit, This Is Spinal Tap, and Bon Jovi provide touchstones for the author’s ruminations. One chapter, “Six Degrees of Jonathan Cilley,” reads like a variation on the Kevin Bacon game. Quietly, though, Griffith pivots from riffs on REM to quotations from Borges and Nabokov. These shifts from comedy to philosophy never seem jarring; they correspond with the author’s observation that death, like Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, is the great leveler. “It’s hard to cling to the idea of social superiority when the formerly bright lines between high and low are dimmed, blurred, or effaced altogether,” Griffith writes.

This collection is replete with pop-cultural references that will appeal to Griffith’s fellow Gen X readers. Smokey and the Bandit, This Is Spinal Tap, and Bon Jovi provide touchstones for the author’s ruminations. One chapter, “Six Degrees of Jonathan Cilley,” reads like a variation on the Kevin Bacon game. Quietly, though, Griffith pivots from riffs on REM to quotations from Borges and Nabokov. These shifts from comedy to philosophy never seem jarring; they correspond with the author’s observation that death, like Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, is the great leveler. “It’s hard to cling to the idea of social superiority when the formerly bright lines between high and low are dimmed, blurred, or effaced altogether,” Griffith writes.

Griffith, a professor of creative writing at the University of Cincinnati and lecturer at the Sewanee School of Letters, wants his essays to capture the non-linear, contingent nature of existence. Progress is an illusion, a label placed retroactively on a jumble of events. “We are poor, forked animals who live most of our lives, and thank God, in a state of ungress, regress, and circumgress,” Griffith avers. He likens his technique of wandering among tombstones looking for stories to “rhapsodomancy, the ancient mode of divination that involves flipping open a manuscript of poems at random.” He calls his method “graveyard-walk-omancy,” a narrative form driven by “impetus and accident.”

Griffith’s associative prose moves with the rapidity and vector redirections of a pinball machine. His chapter on drinking in Cincinnati, the nation’s “number-one most besotted” city in 1880, drifts from pub crawling with friends (“a rigorous, academically legitimate research technique that we called the Bender”) to the temperance movement to the invention of the beanbag.

The quality that ties the essays together is the “persistent strand of autobiography” — that is, Griffith’s own sensibility, honed by decades of writerly observation. He confesses that he is “a sucker for selflessness,” for stories of “self-sacrifice.” Griffith draws our attention to forgotten toilers (“editors, translators, single parents, pit crews, defensive stoppers in basketball”) with the knowledge that we too are headed for the ash heaps of history. The most impressive achievement on The Speaking Stone is that, in Griffith’s hands, such somber observations appear to be causes for celebration.

His knack for light humor enables Griffith to tackle serious issues — notably, the recurrence of racial violence in Cincinnati — without succumbing to despair. Griffith continually returns to the lesson of Spring Grove: “Immortality is capricious, a shape-shifter, and there’s no guessing what our legacies will be, if we are lucky enough to have them.” If we are supremely lucky, our stories will be told by someone like Michael Griffith, who possesses the vision and humanity to perceive, beneath our flaws and foibles, the unsung heroism of our mortal acts.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.