A Good Man in a Nest of Evil

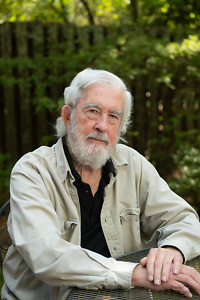

Curtis Wilkie reveals the story of a brave man who informed on the Mississippi KKK

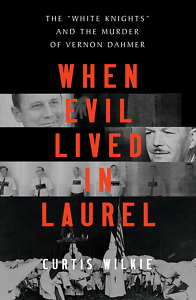

The latest book by legendary journalist Curtis Wilkie, When Evil Lived in Laurel, is a true-crime thriller. It immerses readers in the bone-chilling schemes of Mississippi Klansmen in the 1960s and illuminates the heroics of a martyred civil rights activist and a courageous FBI informant. While chronicling the carnage and folly of far-right extremism and racial injustice, it casts shadows that stretch to the present day.

Wilkie, who spent part of his childhood in Oak Ridge, was a student at the University of Mississippi during its 1962 crisis over the admission of James Meredith, and he went on to a long career in journalism with the Clarksdale Press-Register, Wilmington News-Journal, and Boston Globe. From 2004 to 2020, he was the Kelly G. Cook Chair of Journalism at the University of Mississippi. He is the author of six other books, including the memoir Dixie: A Personal Odyssey Through the Events That Shaped the Modern South and the acclaimed The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign, co-authored with Thomas Oliphant.

He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: At the center of this book is Tom Landrum, the white Mississippian whom the FBI recruited to inform on the White Knights of the Mississippi Ku Klux Klan. Who was Landrum? Why did he agree to do it? What were the costs?

Curtis Wilkie: At the time, Landrum was a 33-year-old youth court counselor troubled by the terroristic activities of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan operating out of his hometown, Laurel, Mississippi. After a courthouse official tried to recruit him to join the secret brotherhood, Landrum decided to respond to a far different request from another friend, a local FBI agent: to become a volunteer informant. He joined the Klan and for four years reported to the FBI on every meeting he attended, naming names and sending warnings of people and places targeted by the Klan.

It was a dangerous assignment — for which he was paid nothing — carrying risks not only to him, but to his wife and five children. The White Knights were known as the most virulent Klan faction in America, responsible for some of the era’s most horrific murders. But Landrum agreed to do it to help break the group’s hold on his community.

Chapter 16: How did you come to this story? How did you discover Landrum’s role and the rich sources that put readers in his shoes?

Wilkie: No one knew of Landrum’s undercover work for a half-century. Then, a few years ago, he was identified as a Klansman in a locally published book. Fearing that he might someday be linked to the Klan, Landrum originally had asked for a private letter from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover that would make clear his role, but Hoover was so determined to control news about his bureau that he refused something like this.

In 2018, near the end of Landrum’s life, his family approached me to see if I would be interested telling the story. They showed me hundreds of pages of his written reports to the FBI that offered a rare inside look into the organization that had terrorized Mississippi during the 1960s, when I was a young reporter in the state. Of course, I was interested. In Landrum’s papers were descriptions of clandestine gatherings deep in the Piney Woods, details of racist rituals cloaked in pseudo-Christianity, reports of vows to strike against prominent Blacks, and accounts of obsessions, arguments, threats, and suspicions that spilled out at meetings. It was clear the White Knights were a witch’s brew of racial hatred and paranoia.

I was able to interview Landrum and his wife, Anne, a number of times at their home near Laurel before his death at Christmas 2019. Meanwhile, I discovered a valuable collection at the nearby University of Southern Mississippi library: several thousand pages of FBI material used in the investigation of the White Knights.

Chapter 16: The crime upon which the book hinges is the White Knights’ firebombing of the home of Vernon Dahmer, which resulted in his death. Why did they target Dahmer? What were the consequences?

Chapter 16: The crime upon which the book hinges is the White Knights’ firebombing of the home of Vernon Dahmer, which resulted in his death. Why did they target Dahmer? What were the consequences?

Wilkie: In the 1960s, Dahmer was not only president of the NAACP in Hattiesburg, a city just south of Laurel, but one of the leading figures involved in voter registration work in the state. Because of Dahmer’s success in the face of Klan attempts to intimidate him, Sam Bowers, the Imperial Wizard of the White Knights, imposed a decree of “Code Four” — elimination for Dahmer.

On a winter night in 1966, a gang of eight White Knights, riding in two cars, burned down Dahmer’s home and neighboring country store. He helped his family escape, fighting off the Klansmen in a gun battle before climbing out a back window. But his lungs were seared and he died a few hours later.

More than 100 FBI agents were dispatched to the state to lead the investigation. With the help of Landrum’s tips about evidence he learned had been left behind by the raiding party, more than a dozen Klansmen, including Bowers, were rounded up within two months.

Over the years, state and federal prosecutors conducted a series of trials with mixed results. There were a few convictions and many mistrials, some caused by Klansmen planted on juries by local officials. In 1998, Bowers was finally found guilty and imprisoned for the rest of his life. I covered that trial for the Boston Globe.

Chapter 16: Was justice served in the Dahmer case? Why or why not?

Wilkie: The ultimate result of the White Knights’ campaign of terror proved counterproductive. Their infamous murders of three young civil rights workers in Neshoba County, Dahmer’s death, and countless church burnings and bombings caused many white Mississippians to recognize the consequences of mindless resistance to equal rights and justice.

Chapter 16: Does When Evil Lived in Laurel provide lessons for us today? What might we learn about ourselves?

Wilkie: Nationwide, today, there are echoes of the elements in this story: racial tensions, campaigns to secure voting rights for Black people, and efforts to deny them that right by some elected officials.

In the earlier struggle, Tom Landrum’s commitment reminded me of a statement attributed to an 18th-century Irish philosopher, Edmund Burke: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.”

Tom Landrum was a good man. We can never have enough good men and women.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.