Shades of Humanity

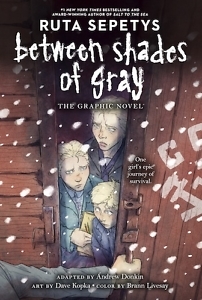

Ruta Sepetys’ young adult masterpiece becomes a graphic novel

A decade ago, Nashville writer Ruta Sepetys enjoyed “the kind of kind of year every debut novelist dreams of” with the publication of Between Shades of Gray, a young adult novel. The story, which follows a 15-year-old girl deported from Lithuania to Siberia during Stalin’s reign of terror, became a Golden Kite winner and an international bestseller, published in over 60 countries and 40 languages. It led to the 2018 feature film, Ashes in the Snow. Now, 10 years after its original release, Between Shades of Gray has been adapted to a graphic novel by Andrew Donkin, with illustrations by Dave Kopka, color by Brann Livesay, and lettering by Chris Dickey.

The visual format makes Sepetys’ difficult tale of a harsh, largely forgotten history more accessible to teens, but beyond that it allows the protagonist, a talented young artist, to come alive in a way that transcends the original. A love of art gives young Lina the strength to live in the face of constant deprivation. As she draws, her work develops literally before the reader, softening the terror of her world, even as Kopka’s watercolor style softens the vast Siberian landscape surrounding her.

Graphic novels have successfully portrayed other dark periods of modern history, of course. Noted examples include the Holocaust of Art Spiegelman’s Maus, the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer, and the American civil rights struggle as lived by the late John Lewis within the March trilogy. Josh Neufeld, author of the graphic novel A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge, calls the form “one of the most personal and intimate ways to tell true stories.”

Before Sepetys, herself the daughter of a Lithuanian immigrant, created the fictional Lina, she spent five years researching the reality of Lina’s world, interviewing survivors of the gulags and traveling to Lithuania and the locations of prison camps depicted in the novel. The intimacy of the graphic form delivers that reality viscerally, transcending even film as an engrossing medium. Kopka takes full advantage of arresting double-page spreads, unusual perspectives, action details, silent landscape panels, and other tools of the comics artist, while Donkin’s spare adaption pares the best dialogue and observations of the novel to fit the visual richness of the pages.

In two long vertical panels that float over a map of the Baltics, Lina reflects on what has become her daily routine as the prisoners, weak from lack of food, work in a field of beets while watched over by young Soviets with rifles. “Every other night they woke us to sign the document that would sentence us to twenty-five years,” reads a text box near the top of the page. And further down, above two women bent low over the plants: “We escaped to a stillness within ourselves and found peace there.”

In two long vertical panels that float over a map of the Baltics, Lina reflects on what has become her daily routine as the prisoners, weak from lack of food, work in a field of beets while watched over by young Soviets with rifles. “Every other night they woke us to sign the document that would sentence us to twenty-five years,” reads a text box near the top of the page. And further down, above two women bent low over the plants: “We escaped to a stillness within ourselves and found peace there.”

Despite the deprivations of the camps, Between Shades of Gray is also a teenage romance, as Lina first befriends an older boy named Andrius, then rejects him as a spy and traitor, and eventually comes to understand and love him. The story escapes the drudgery of camp life with flashbacks to Lina’s carefree youth, scenes that will feel familiar to contemporary teens despite vast differences of time and place.

Lina’s fascination with Edvard Munch allows bits of the artist’s life and work to appear throughout the book. As Lina furiously sketches scenes of camp life, the artist becomes more than his famous existential painting, The Scream. Readers look over Lina’s shoulder to a face emerging on scrounged paper, her fury expressed in four small text boxes that conclude: “I thought of Munch and his theory that pain, love, and despair were links in an endless chain.”

While the story is not one that can possibly reach a “happy” ending, it does allow satisfying resolution for some — if not all — of its characters. In a two-page author’s note at the end, Sepetys herself, drawn documentary style, speaks directly to readers from her library. She addresses the reality of the Baltic peoples deported by Stalin and reveals that one of the book’s characters — among the many good, bad, and in-between — was an actual person realistically portrayed. She explains that for surviving families, even referring to an imprisoned person remained a dangerous crime in the Baltics for decades after World War II.

“Please research it,” she says of the book’s historical sweep. “Tell someone.” Readers of all ages who follow this beautiful, painful book to its conclusion will be moved to do exactly that.

Michael Ray Taylor is the author of Hidden Nature: Wild Southern Caves. He chairs the communication and theatre arts department at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas