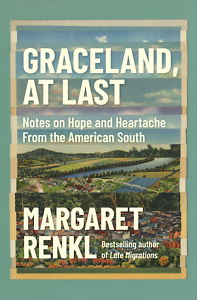

The Word from Nashville

Margaret Renkl surveys a complex, confounding region

With no pretense to being an expert on the subject, I believe the first newspaper columns were probably those brief essays written by the likes of Addison and Steele, Dr. Johnson, and other 17th- and 18th-century writers for publication in London coffeehouse news sheets like the Tatler and the Spectator. If you love newspapers, it’s likely you will have your own favorite columnists — mine might be the late Eugene McCabe, who wrote a satirical daily column, “The Fearless Spectator,” for the San Francisco Chronicle from the mid-50s until his death in 1983.

Newspaper columns typically being a big-city phenomenon, I was delighted when op-eds by Margaret Renkl began to appear five or six years ago in The New York Times. An Alabamian by birth, Renkl lives in Nashville, which provides the vantage point for most of her columns. Over the past few decades, the city has grown, but its population still officially comes in at under one million. Twelve percent of Nashvillians are now foreign born, and many speak a language other than English at home. In 2009, voters rejected an amendment to the city charter that would have made English the city’s official language — largely symbolic, of course, but somewhat surprising in a state like Tennessee.

Renkl provides a good introduction to the contemporary South and offers a corrective to some persistent oversimplifications. She succeeds in steering clear of our infamous national polarization by regarding the United States not, as some do, as an idea, an experiment, or some other such thing, but as a place. In this regard her approach is traditionally Southern, as is her habit of addressing particulars rather than generalizations. Almost everything she writes about begins with a local focus. The collection of her columns under review here is divided into six sections, leading off with “Flora & Fauna” before moving on to “Politics & Religion” and “Social Justice.” The book is rounded off with sections on “Environment,” “Family & Community,” and “Arts & Culture.”

Graceland, at Last makes good on Renkl’s claim in her introduction: “This book will introduce a variety of Southerners: Black and white and brown, urban and rural, religious and anti-religious, conservative and progressive, infuriating and inspiring.” Most of these people defy stereotyping. I was glad to be told, for example, about Dr. Leo M. Hall, “a decorated medical school professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham,” who also taught a high school religion class on Sunday afternoons in Renkl’s younger years. I wouldn’t have expected to see a molecular geneticist teaching religion to Southern teenagers. And I liked being reminded of what Faron Young, the most popular country & western singer of his time, did when he learned radio stations were refusing to play Charley Pride’s records once they learned Pride was Black: “‘You son of a bitch, you go back there and tell that son of a bitch that manages your station if he takes Charley Pride off,’” Faron Young told one of them, “‘take all my records off.’”

Faron’s mother might have washed his mouth out with soap, but thank goodness for his pioneering attitude about race. When it comes to conservative Southern attitudes toward LGBTQ people, Renkl tells this story illustrating the seemingly contradictory mindsets of many Southerners: “Decades ago, when I was still a teenager in Alabama, I heard my grandmother refer to some new neighbors as the Tallyho Boys. Turns out a gay couple had bought or inherited a farm just down the road from her. The good ladies of that rural community welcomed the couple with poundcakes and homemade jelly, but would they have voted for a political candidate who supported marriage equality? Not a chance.”

Faron’s mother might have washed his mouth out with soap, but thank goodness for his pioneering attitude about race. When it comes to conservative Southern attitudes toward LGBTQ people, Renkl tells this story illustrating the seemingly contradictory mindsets of many Southerners: “Decades ago, when I was still a teenager in Alabama, I heard my grandmother refer to some new neighbors as the Tallyho Boys. Turns out a gay couple had bought or inherited a farm just down the road from her. The good ladies of that rural community welcomed the couple with poundcakes and homemade jelly, but would they have voted for a political candidate who supported marriage equality? Not a chance.”

She reminds us that “the South is more than the people who live here. It is also the unfathomable natural beauty of a place that is still predominantly rural and very often wild. This is a gorgeous land shot through with rivers running like lifeblood through ancient mountains and old-growth forests … .” The lyricism of some of Renkl’s language is a reminder that she began her writing life as a poet. In her 2018 column eulogizing John Prine, she focuses on “Paradise,” which may be his best-known song. It’s a lament for a lost Eden destroyed by the rapacity of the coal industry. Here’s one verse:

The coal company came with the world’s largest shovel

And they tortured the timber and stripped all the land.

Well, they dug for their coal till the land was forsaken,

Then they wrote it all down as the progress of man.

“The difference between the way ‘Paradise’ resonated with listeners in 1971 and the way we hear it now,” Renkl writes, “is that back then we didn’t know what coal was doing to the planet itself.” In his 2018 State of the Union address, a former US President proclaimed, “We have ended the war on beautiful, clean coal.” Anyone who has driven through Appalachia and seen the barren, deforested moonscapes and clogged, polluted rivers and streams created by what is called mountaintop removal mining might dispute the adjective “beautiful,” and the estimated 1,000 miners who die yearly from black lung disease might well quibble with the word “clean.”

A practicing Catholic, Renkl’s religion gives her a solid basis for relating to other citizens of this deeply religious region. Rounding out her essay on John Prine, she says, “His primary mode of persuasion is the story, just as the primary mode of persuasion for the biblical Jesus is the parable. … A parable trusts the story to do the work of interpretation. A parable resists polarities: people listening to a story can’t immediately know whether they belong among the speaker’s ‘us’ or the speaker’s ‘them’.”

Constantly in search of consensus though she is, she at the same time does not shy away from addressing contentious issues. In her column, “There Is a Middle Ground on Guns,” she approaches the matter from the position of someone who knows how to use a firearm. She speaks of the shotgun her grandfather kept at the ready on his farm and adds that “My father, a salesman who often had appointments in crime-ridden neighborhoods, carried a handgun on nighttime calls and taught me to shoot it when I was fourteen. It never crossed their minds that I or anyone else might pick up one of those guns without a very good reason.” Invoking polls that show wide support for background checks and other commonsense measures to help control gun violence, she laments how our legislators remain in thrall to the NRA. “There is no need for polarities here,” she confidently asserts.

Richard Tillinghast’s most recent nonfiction work is Journeys into the Mind of the World: A Book of Places. A native Memphian, he has never been to Graceland.