Charting a Course

A childhood friendship filled with possibility

Jim Beattie has a face subject to frequent high color. He is a friend who lives several houses down the street, and he’s my classmate one year in either third or fourth grade. Like many children in the elementary years, we are running buddies for only a while, but most definitely from age 8 to 10.

Whether in heat or cold, Jim’s cheeks flush with excitement. He has a sturdy shock of dark gold hair, freckles, and a ready smile. Our adventures are unparalleled. If we rendezvous somewhere along the street, ready for whatever comes next, he doesn’t wave as he approaches. He shoots his arms up over his head like an airport flagman or yells “What, ho!” as though the asphalt street were the bounding main.

We are different in many ways, but what we share makes any difference seem negligible. What we share is quite probably something that neither of us knows we are looking for. We have good teachers and encouraging parents. Apparently, though, neither of us has previously found the right friend to recognize and spark our love of words and exploration. We hunger for reading and imagining, and we pass uncounted hours devising indoor occupations and outdoor games and journeys that transcend their suburban context and have blessedly nothing to do with team sports or Cub Scouts.

Though I’m a natural swimmer and fast runner, team sports seem pretty much an alien aspect of human existence to me. When some gaggle of boys begins to pick teams near a basketball hoop and an ill- informed newcomer points at me and says, “Get him, he’s tall,” my blood runs cold, and the kinder of my acquaintances look away pretending to see something off in the middle distance.

I am on a Little League baseball team for a couple of seasons and find everything about it tedious from the required technical skills to the itchy over-warm uniform. My career’s sole highlight occurs when one bright afternoon I’m assigned to center field (possibly because that’s where I might do the least damage). The first batter hits a pop high into the air. I look up. The setting sun is, full force, in my eyes. There is nothing but glare. I hold up my glove in front of my face. I hear and feel the ball land in it with a solid smack. I am so stunned that I’m not sure what has transpired, but there is some cheering from our team’s family members and I try to act as nonchalant as possible, as if my spontaneous act of blind self-protection is instead a moment of glory born of honed skill and almost casual effort.

Of Cub Scouts there is not much to be said. Even our den mother, Mrs. Carlisle, seems to manage the arcane proceedings with her tongue in cheek. She leads us through our pledge to follow Akela and obey the laws of the pack, but a twinkle in her eye suggests that perhaps she finds it all just a bit much. In fact, she may be the liveliest aspect of the weekly gatherings. Festive, she has eyes that dance, a husky voice, and a laugh that erupts at any opportunity, sometimes for no apparent reason at all. If there is a lull in the proceedings, she widens her eyes into glittering green orbs and claps her hands together once: “Okay, gang, let’s have some fun.” She wears colorful capri pants and diaphanous blouses. Afterwards, when one or two mothers pick us up at the foot of her drive, she says things that make them laugh, too, and lights up the cigarette she has undoubtedly wanted for the past 90 minutes.

It might be a safe bet that in another half-hour or so, when her husband arrives home from his office, they too may share a laugh and enjoy a cocktail or two before dinner. Once, in her quest for activities to keep us occupied for our “meetings” she has us “make” tie racks for Father’s Day. She’s had someone cut out the shapes of dogs — terriers sitting faced away with heads turned to the side, about 10 x 5” and probably an inch thick. Our job is to choose colors, paint our wooden canine, and when the quick-drying paint is ready, affix with strong glue a tail that curves out and slightly up. On this spritely tail our fathers’ ties, though unhelpfully layered and tangled, will hang. Mrs. Carlisle seems even more festive than usual when we leave that afternoon, pleased that the gluing and painting have been incident-free and everyone is departing with a dog, however mongrel. Perhaps even more important, we all, including Mrs. Carlisle, have, at least this once, something to show for this whole aimless Cub Scout thing.

Such well-intentioned group functions feel as though they are happening to, being endured by, someone else. The real fun, the real life in these years lies in the inventions and pursuits that Jim Beattie and I concoct. Instead of enforced game strategies and arbitrarily planned activities, we imagine our way from one interesting involvement to the next.

On wet or bitter days, our theatre of operations is indoors. For hours we draw pictures of cityscapes and landscapes, ships and houses. Flung about on den sofas or chairs we read like fiends, not the school assignments with which we quickly dispense but books of our own choosing from a nearby branch of the public library. We never talk about them at length. These are not book report sessions or an early form of book club. We’re developing an appreciation for the private bond between reader and text, the journey one must take alone. Still, we exchange bits of information gleaned, notions sparked. “Listen to this!”

Jim’s father, a major in World War II, has let him have troves of pamphlets, photos, and memos, and mine has given me some old studio distribution catalogues from my grandfather’s years in the film business, along with playbills and posters. We examine like fussy curators these relics that have not made our families’ cut as memorabilia. While many of our peers are trading baseball cards, we’re reading aloud from our encyclopedias, subjects arising on whim or with concerted purpose, about the kings and queens of England, U.S. presidents, the great ocean liners, medical discoveries, developments in agriculture, authors, Marco Polo, art, the annals of weather events.

Fascinated with geography, we never tire of staring at globes, slowly turning them, scrutinizing them, poring over maps in the encyclopedias and in burgeoning stacks of National Geographics. My father travels sometimes with his work, and he passes on to us road maps of our own and adjacent states. On vacations, more exotic finds are to be had for free or perhaps a nickel from the racks near the doors of gas stations. “Look! Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas! Multiple seacoasts!” With these maps spread out on the floor, we use pencils and colored markers to create countries, principalities, city states. We designate capitals, strategically annex or cede territories, conduct wars, achieve peace agreements, send expeditions to far-flung areas to explore, establish colonies, and trade.

In every season, in any weather that can possibly be considered decent, we roam outdoors. On bright winter days, the couple of hours between school dismissal and early darkness feel like the gift of another whole day; of all the long summer twilights of childhood, ours spent together seem the most unending. We don’t ride our bikes in a desultory manner. They are sleek, fast vessels, planes, spaceships, means of flight. We ride them for miles and miles, exploring, going always farther afield, and as we finally head home, we flirt with the imperceptible exhalation of the last light and parental rules.

Our favorite haunts are a golf course several blocks from our street and, a mile or so in the opposite direction, an undeveloped piece of land that may be about 12 or 15 acres. The tract is heavily wooded with a couple of paths winding through it. The golf course has many copses and a small forest in the middle. Both destinations have a rarity in our flat town: hills. We enjoy nothing better than losing ourselves in these mysterious, shaded, rich-scented retreats. The hills and ravines engage us, drawing us again and again to the difference the landscape offers. The vestiges of old forests set these places — and us while we are there — apart from the somewhat bland texture of life in our post-WWII city suburb. Here among the giant trees, the sounds of the birds, and the seasonal winds, we find a catalyst for our imaginings, our quests, our enactments of the stories we love and invent.

Jim has a foldable pamphlet for identifying birds, and sometimes we walk quietly along the paths, or off them, and make our most informed guesses. I have a small book with which we begin learning the trees. We choose favorites to whom we pay regular homage. We slip easily from ourselves into other personas and generously take turns being our favorite heroes from literature and history and film and television, sometimes creating hybrid figures fashioned partly from these sources and partly from our own whole cloth.

Some days we may be Robin Hood and Little John, roles that require specific accoutrements. From the spreading mimosa tree in my backyard, we are allowed to cut two long, straight, lower branches, sturdy but lightweight enough for easy handling. These double as walking sticks and the cudgels so essential in clearing away off-path undergrowth and to have at the ready should any of the Sheriff of Nottingham’s thugs suddenly loom. Other days we alternate being an early-18th century explorer from Virginia and a Cherokee guide explaining the local flora, fauna, weather, path-finding, omens. With only a very few words of shared language, we must devise other means of communication including but not limited to eloquent sounds, signals, and gestures.”

There are closely orchestrated adventures, revivals of favorites, new ideas and riffs that arise spontaneously and either play out almost as quickly or live on with piqued interest and plans for elaboration.

In our play, Jim and I coexist in a landscape of our own discovery with an atmosphere of richer oxygen. In our friendship we are somehow less the prescribed children we have dutifully been and, more freely and spiritedly than anywhere else, the unique individuals we will become. The world opens up in a new way, more becomes possible, there is a new kind of magic and an altered reality. Without understanding it, we are finding a truer animation, perceiving a glimpse of some light, some beam within us and between us and beyond us that needs to be acknowledged, communicated, followed.

Of the 50 United States, I have now seen all but North Dakota. I have spent at least some time on five continents. By ship and by air I have crossed two oceans, three seas, and seven gulfs. I have known many adventures. One face of adventure that remains undiminished is that of Jim Beattie. I see him waiting for me at my back door. We are 9 years old. His cheeks have that vivid flush. His brows lift. His eyes are alert.

Readiness is all, and imagination is both the appetite and the fuel.

One of us says, or perhaps together we say, “Let’s go!”

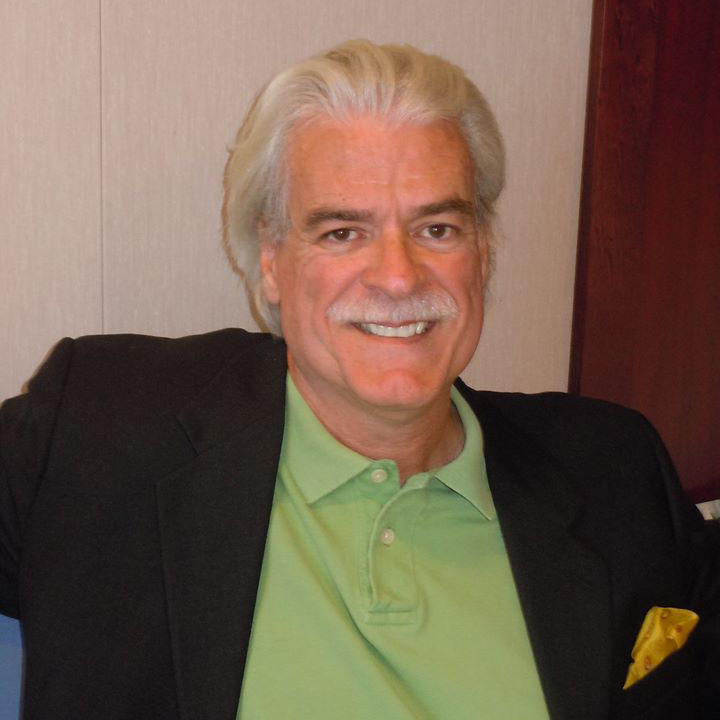

Copyright © 2022 by Hadley Hury. Hadley Hury’s poetry has appeared in numerous journals and magazines, and a collection, Almost Naked, was published in 2018. He is the author of a novel, The Edge of the Gulf, and a collection of stories, It’s Not the Heat. He lives in Memphis with his wife, Marilyn Adams Hury.