A Tennessee Memory of Sidney Poitier

The year was 1966, and two icons came to honor Fisk University’s centennial

January 6, 2022, was a day of multilayered sadness. Not only was it the first anniversary of an insurrection — the deadly attack on the U.S. Capitol — it was also the day Sidney Poitier died.

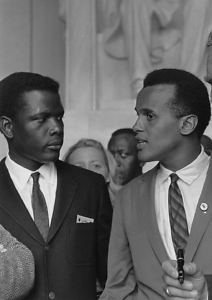

With this passing of an American icon, my friend Hugh Moore shared a treasure I had forgotten — an article I had written in the Vanderbilt Hustler, our student newspaper, about a visit Poitier made to Fisk University. The year was 1966, the 100th anniversary of Fisk, and Poitier and his friend Harry Belafonte were the centennial speakers.

As Hustler editor, Hugh had suggested that he and I cover the event. We had seen Poitier’s most recent movie, A Patch of Blue, and we understood — how could we not? — the cultural relevance of his career. In films like Lilies of the Field, A Raisin in the Sun, and now his latest, Poitier embodied a reality he thought America must see: a Black man of dignity and strength. Three films would follow in 1967 — In the Heat of the Night (which won the Academy Award for Best Picture), To Sir with Love, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, all of which dealt head-on with the enduring legacy of racial segregation.

By the time of his visit to Fisk, Poitier was well on his way to becoming one of the most popular actors in the country. Belafonte was as legendary for his support of the civil rights movement as he was for his calypso singing. Hugh and I were a little starstruck. We were also surprised when the two celebrities agreed to be interviewed, even briefly, by a couple of white guys from the student newspaper across town.

The interview itself was uninspiring. We asked something about the role of universities in American life, and Poitier replied, “Art cannot survive without the full support of universities, which are the center of culture.” Maybe if there had been more time, he would have talked about Fisk University in particular, for most assuredly he knew its story.

He understood, as his speech made clear, that as soon as the Civil War was over, abolitionists from the American Missionary Society were traveling the South, making their plans for what came next after the end of slavery. Many of these were white men, like John Ogden, Erastus Milo Cravath, and Edward Parmelee, the founders of Fisk, who worked with the assistant commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau, Clinton B. Fisk, to secure a former military barracks as the site for a school.

Classes began on January 9, 1866, and within a few months, enrollment had soared to 900 students. For the next 100 years, Fisk stood as a symbol of Black aspiration, and by the civil rights years, many of its students were leaders in the movement. Two of the most prominent were Diane Nash and John Lewis, who had transferred to Fisk from American Baptist Theological Seminary.

Classes began on January 9, 1866, and within a few months, enrollment had soared to 900 students. For the next 100 years, Fisk stood as a symbol of Black aspiration, and by the civil rights years, many of its students were leaders in the movement. Two of the most prominent were Diane Nash and John Lewis, who had transferred to Fisk from American Baptist Theological Seminary.

April 19, 1960, was a watershed day for the movement in Nashville. Early that morning, a bomb exploded at the home of Z. Alexander Looby, an African American attorney who represented students arrested during Nashville’s lunch counter sit-ins. So powerful was the blast that Looby’s house was nearly destroyed. Down the street, more than 140 windows were shattered at Meharry Medical College, and dozens of people were cut by the glass.

Miraculously, neither Looby nor his wife were hurt. But outrage swept through the Black community, and the students decided to march in protest. In what would become a defining image of the decade, the ranks of the marchers swelled to several thousand as they walked in silence toward City Hall. Mayor Ben West waited for them on the steps.

At first the mayor seemed nervous and defensive, but Diane Nash approached him calmly. Speaking with resolve, she asked if West would use his office to end discrimination in Nashville.

“I appeal to all citizens to have no discrimination,” he replied, “no hatred, no bias, no bigotry.”

Nash continued to push: “Do you recommend desegregation of the lunch counters in the stores?”

“Yes,” said West.

It was a moment of triumph for the civil rights movement, one that resonated throughout the South. Thus, at Fisk’s centennial celebration, it was more than a cliché when Harry Belafonte said of its students, “The future of America rests in their hands.”

Looking back on it now, that is the dominant memory Hugh Moore and I carry from that day — the extraordinary level of mutual respect between two major celebrities and the students they had come to address. In our article for the Hustler, we wrote: “The two stars spoke to a packed house in the Fisk Auditorium … then greeted students informally at a reception that afternoon… For more than three hours they signed autographs and conversed about any subject from the weather to civil rights.”

When a Fisk official informed the entertainers that it was time to go, their plane was scheduled to leave in 30 minutes, Poitier replied: “No, we’ll catch a later plane.”

It occurred to me then, as it does now, a year after his death, that this simple display of humanity — the clear priorities of a cultural hero — may have been the most memorable lesson of an unforgettable day.

Copyright © 2023 by Frye Gaillard. All rights reserved. Frye Gaillard, author of A Hard Rain: America in the 1960s and The Southernization of America, is writer-in-residence at the University of South Alabama.