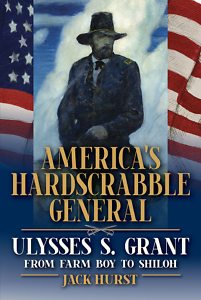

The Quiet General

Jack Hurst reveals the secret of Ulysses S. Grant’s success

When reports of the capture of Confederate Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River were published in February 1862, the Northern press, desperate for good news from the front, hyped the success of the relatively unknown brigadier general responsible for the victory. Ulysses S. Grant’s name was often shortened in print to U.S. Grant, inviting speculation about what the initials stood for. Some enterprising reporter, noting that Grant had refused to negotiate terms with his enemy, announced that the U.S. stood for “Unconditional Surrender.” As described by Jack Hurst in his new biography, America’s Hardscrabble General: Ulysses S. Grant from Farm Boy to Shiloh, both the nickname and the reputation stuck, and Grant quickly became one of America’s most celebrated generals.

For Grant, the acclaim won in the Civil War was the culmination of a life of hard work, little success, and much failure. Hurst maintains that it was precisely the overcoming of life’s hardships that built a man of such character and determination, one almost uniquely qualified to lead the Union armies to victory. In fact, Hurst uses Grant’s example as evidence that in America it is not always the privileged and wealthy leading from the top who make the difference, but the quiet, overlooked working class that produces leaders. In describing Grant as “hardscrabble,” Hurst is both stating a fact and calling attention to a uniquely American tradition, that humble beginnings can produce greatness.

In Hardscrabble General, Hurst notes that Grant’s origins were much different from the vast majority of other Civil War generals. In the 19th century, most generals came from the upper classes, people who could afford to go to college and felt entitled to lead others. This was especially true of the men who became Grant’s enemies in the Confederate armies, men who had largely grown up having their work done for them by enslaved people. Not Grant, who was raised in Ohio by a family who knew what it meant to struggle. “Such an existence,” writes Hurst, “instilled second-nature self-reliance, the habit of working very hard, a perpetual sense of urgency, and a drive to get things done with whatever resources were at hand, rather than wait and hope for eventual assistance.”

Grant never sat around waiting for assistance, whether in civilian or military life. As a boy, he worked on the farm and in his father’s business, where horses were the engines of production. By the time he was 5, Grant was an accomplished equestrian and never lost his love of horses or his ability to become one with them when he was in the saddle. He also learned mechanics and lumbering and other useful skills that would, in later life, allow him to connect easily with the men he commanded, men who by and large came from the same social class. Grant’s only privilege came with an appointment to West Point, forced on him by his father, who wanted him to become somebody. Grant got the education, though he never wanted to be a soldier — he hated the spilling of blood, whether animal or human.

Grant never sat around waiting for assistance, whether in civilian or military life. As a boy, he worked on the farm and in his father’s business, where horses were the engines of production. By the time he was 5, Grant was an accomplished equestrian and never lost his love of horses or his ability to become one with them when he was in the saddle. He also learned mechanics and lumbering and other useful skills that would, in later life, allow him to connect easily with the men he commanded, men who by and large came from the same social class. Grant’s only privilege came with an appointment to West Point, forced on him by his father, who wanted him to become somebody. Grant got the education, though he never wanted to be a soldier — he hated the spilling of blood, whether animal or human.

But soldier he did, earning a reputation for bravery and leadership during the Mexican-American War, where he met many of the men he would later fight with or against when slavery divided the nation. He even tried soldiering in peacetime but became so despondent over separation from his wife and children, and so affected by drink, that he quit the army. It was the following seven years out of uniform, the lowest point in Grant’s life, that Hurst describes as being perhaps the greatest catalyst for the general’s success. The failures, notes Hurst, “doubtless helped immunize against countenancing defeat.”

Hurst, a native Tennessean, has written other books about Grant and the Civil War and knows his subject well. His prose is plain and clear, like the writing of the man he so obviously admires. In Hardscrabble General, he provides a fine portrait of a leader who never sought wealth or notoriety, who cared much more for the men he commanded and the nation that had educated him than he did for the headlines he made. A man whose life lessons taught him the humility with which he approached his job and the clarity of purpose needed to see a thing through to its conclusion. To win.

A Michigan native, Chris Scott is an unrepentant Yankee who arrived in Nashville more than 30 years ago and has gradually adapted to Southern ways. He is a geologist by profession and an historian by avocation.