Conflicted

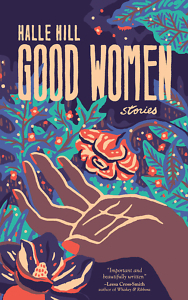

Good women don’t always behave well in Halle Hill’s debut story collection

Though short stories are often an entry point for an emerging writer, a story collection is comparatively rare when considered next to the bounty of novels and nonfiction. Some collections arrive highly anticipated from well-established authors, but the most exciting might just be a debut, especially one that lands with the force of Halle Hill’s Good Women. In this powerful collection, Hill gathers a chorus of women, each fumbling and fascinating in unique ways. Though the stories stand alone, together they offer a brilliant composite of what it might mean to be a Good Woman.

From the first paragraphs of the book, Hill demands attention. In the opening story, “Seeking Arrangements,” Krystal’s narrative voice is brash but vulnerable, confessing in the first few sentences to being nervous and describing the way she and Ron take all three seats in their bus row: “My toenails glisten in Cha-Ching red polish and my feet are spread across his lap. Now this is luxury!” She overshares, seeming too comfortable even as her mental chatter reveals her uncertainty. Krystal, who is Black, understands that her situation with Ron (who is white and old and paying her to be there) is unsavory. She could escape, but she doesn’t, and the reader understands. The story is barely a flash, a breath, a blink, but it leaves the impact of a meteorite.

Hill is a native East Tennessean, and her stories live there as well. Krystal is traveling from Nashville; Maudette (“Honest Work”) works at a fairground outside Knoxville; and Shauna is the only Black woman in her Knoxville church small group. Shauna and her white husband, John, are trying to start a family, but Shauna is secretly still on birth control. Shauna’s story, “Skin Hunger,” is the longest in the collection. It takes its time uncovering Shauna’s complexities, showing off Hill’s skill in different ways.

Shauna’s secret is known from the first sentence: “While baby fever spread among our small group, I knew I’d never have one with John.” After that revelation, Hill lingers over the details of Shauna’s upper-middle-class social group and marriage to John before accelerating the narrative once Shauna goes to Sewanee for her older sister’s retirement party and decides not to return. The plot is a bit predictable here, but Hill captures exactly the tenor of their social dynamics: the way pregnant Mary-Martha had “been keeping her ring hand on her stomach a lot, especially in conversation with unmarried women. She was having the nursery done in West Elm,” or the way Alice (unable to conceive due to PCOS) “stared at the baseboards I never cleaned and talked about the new ‘pure mama’ non-toxic cleaning supplies she’d been making with thieves oil and white vinegar.”

In “The Best Years of Your Life,” the unnamed narrator works as an admissions counselor for a for-profit university, New U, with offices in a vacant department store. Like most of the women in Hill’s collection, the narrator is direct. She knows her work is a lie. She admits to crying on the way to work most days and tells the reader: “I’ve got a bang situation at the moment. I’m so sad I can barely wash my hair.” She’s hurting, ostensibly because her “sorta-boyfriend” Caden dumped her, but the story is saturated with the guilt she feels about the prospective student she worked on for months, a grandmother from Oneida who plans to go to law school after graduating from New U, hoping to defend her grandson who was wrongly incarcerated. Hill describes the woman: “Her T-shirt read ’World’s Best Meemaw’ and a Tweety-bird keychain held her house keys on a carabiner. It hooked in a loop on her White Stag jeans.” Like the perfect bridge in a solid song, details like these elevate every story in Hill’s collection.

In “The Best Years of Your Life,” the unnamed narrator works as an admissions counselor for a for-profit university, New U, with offices in a vacant department store. Like most of the women in Hill’s collection, the narrator is direct. She knows her work is a lie. She admits to crying on the way to work most days and tells the reader: “I’ve got a bang situation at the moment. I’m so sad I can barely wash my hair.” She’s hurting, ostensibly because her “sorta-boyfriend” Caden dumped her, but the story is saturated with the guilt she feels about the prospective student she worked on for months, a grandmother from Oneida who plans to go to law school after graduating from New U, hoping to defend her grandson who was wrongly incarcerated. Hill describes the woman: “Her T-shirt read ’World’s Best Meemaw’ and a Tweety-bird keychain held her house keys on a carabiner. It hooked in a loop on her White Stag jeans.” Like the perfect bridge in a solid song, details like these elevate every story in Hill’s collection.

When that hopeful grandmother is admitted to New U, she is overjoyed: “‘You’re a good woman,’ she tells me, as she squeezes tighter. ‘Your kindness is changing us, we won’t forget it.’” With those words, Hill makes it clear: All the women in this collection are “good women,” and all of them are conflicted about the things they do that are decidedly not good. They are honest and reflective, and they are also trapped in webs of trauma and historical harm.

Though the women are often seemingly blind to those webs, the reader can see them, and the quiet certainty of them is terribly effective. Hill has crafted a collection worth reading in full, straight through from the first page. Each story builds on the one before it, accumulating into a cohesive whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Sara Beth West got fired from her first job. By her dad. Since then, she’s walked away from many other jobs, including nanny, retail worker, farmhand, choir director, teacher, social media manager, and compost truck driver. Most recently, she left a great job as a public librarian. But the one job that keeps following her around is writer. She writes book reviews and conducts author interviews for Shelf Awareness, Chapter 16, Southern Review of Books, and more. She lives in Chattanooga.