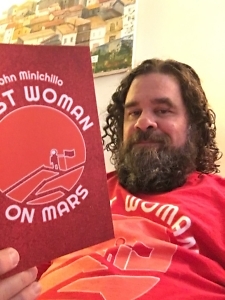

Giving the Lie to Literary Boundaries

The new novel by John Minichillo defies normalcy

Message in the Sky, the new science fiction novel by John Minichillo, offers proof that literary boundaries are an invention, a lie. Here is the first line: “The Trumps and the Clintons were neighbors on Mulberry Court, a winding lane with matching houses, each backyard with a cement patio and a rectangular patch of grass, the yards separated by a privacy fence they sometimes talked over when the mood was right.” It’s above these yards — and this fence — that a spaceship appears.

At first the book reads like sharp sci-fi, with aliens and dystopian forebodings. Then it turns into something less conventional: a satirical gateway to notions that defy simplistic classification. It’s a character-driven story as opposed to one fueled by themes of right and wrong, natives versus invaders, or even futurism. Nashville resident Minichillo brings political ideas and eccentric psychology to a field of writing that, for all its imaginings, is overrun by writers with a penchant for the same old narratives and hierarchies with new robotics and new threats. Minichillo is different, and it’s difficult to categorize his work. As one character remarks, in answer to a question about the existence of space aliens, “We’re all from somewhere. None of us really belongs here.”

At first the book reads like sharp sci-fi, with aliens and dystopian forebodings. Then it turns into something less conventional: a satirical gateway to notions that defy simplistic classification. It’s a character-driven story as opposed to one fueled by themes of right and wrong, natives versus invaders, or even futurism. Nashville resident Minichillo brings political ideas and eccentric psychology to a field of writing that, for all its imaginings, is overrun by writers with a penchant for the same old narratives and hierarchies with new robotics and new threats. Minichillo is different, and it’s difficult to categorize his work. As one character remarks, in answer to a question about the existence of space aliens, “We’re all from somewhere. None of us really belongs here.”

John Minichillo answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: One of the characters in Message in the Sky refers to writing as “outdated technology.” How does technology affect your own writing process?

John Minichillo: These neighboring couples witness a UFO together and it writes symbols in the sky. Amy is obsessed with finding out what it says while her husband, Jim, also a witness, doesn’t believe what he’s actually seen. Amy wants Jim to make a website to show the world and maybe someone will know what the message says. Jim, the skeptic, tells her he doesn’t think advanced civilizations would still use writing: books are cumbersome, reading is slow, line by line. So it’s Jim who has the line, but I’m there with him on that one. It never felt right to me to call writing “technology” (as an anthropologist would) because the way most of us use the word is narrow; it’s fast, light, expensive fun, like a synthesizer laser satellite motherboard.

Chapter 16: How do you define reality? Has your thinking about the nature of reality changed over the course of writing nine novels?

Minichillo: I have written something like nine novels, but I’ve only published five. I’m not sure, but I think you might be asking if this has turned me into Don Quixote. Cervantes was joking, but we do have this notion that escapism (in DQ’s case reading romances) can lead to a kind of madness. A writer, on the other hand, has a different relationship to the world, as one who is required to pay close attention. The world, by the way, hasn’t supplied any good reason for why we’re here, where anything comes from, or what is is.

I’m interested in the nature of reality, which is where biology meets physics, and there are still big unanswered questions. The two hemispheres of the brain don’t agree about what’s perceived. We haven’t figured out gravity, or consciousness, not to mention reconciling quantum states with the macro-world of matter. And matter is what, vibrations? Little tiny pieces-parts? Very smart serious people have guessed it’s all … a hologram? Or flickering shadows on a cave wall?

For UFO believers, the unanswered scientific questions overlap with the UFO phenomenon. Witnesses often come away with the conviction that the craft itself had a consciousness, so that UFOs are technologies of consciousness. They appear to move by manipulating gravity.

For those who are hopeful about UFO disclosure, it’s less about joining the galactic pantheon in a Star Trek universe, and more about the very exciting prospect of solving the physics problems that stumped Einstein. We may be nearer than we realize to potentially learning the truth about gravity, consciousness, and our history on this planet. This is all to say that anyone who thinks they know the true nature of “reality” is probably deluded.

Chapter 16: I want to ask about your characters’ ambition. This book opens with neighboring couples, named the Trumps and the Clintons, noticing an alien spaceship in the sky. A later chapter reads “No one can believe what they’ve seen, but they’re uplifted by the message that was written in the sky, and the crowd emits a joyous roar as everyone gets up and embraces each other, intoxicated by this interlude from the gods. Everyone is happy, relieved of their dearth and buoyant with the gift of life. Until the high priest speaks.” I was curious what the link is between potentialities and ambition, creative greatness, and the very human desire to be godlike.

Chapter 16: I want to ask about your characters’ ambition. This book opens with neighboring couples, named the Trumps and the Clintons, noticing an alien spaceship in the sky. A later chapter reads “No one can believe what they’ve seen, but they’re uplifted by the message that was written in the sky, and the crowd emits a joyous roar as everyone gets up and embraces each other, intoxicated by this interlude from the gods. Everyone is happy, relieved of their dearth and buoyant with the gift of life. Until the high priest speaks.” I was curious what the link is between potentialities and ambition, creative greatness, and the very human desire to be godlike.

Minichillo: I think this might be two questions…

The naming of the characters, calling them the Trumps and the Clintons, is meant to signal satire. We have strong feelings associated with these names and so it’s a shortcut to character types: yuppies who are liberal and yuppies who are not. Or: the people next door who we think we’re better than (which works both ways). This divisive atmosphere is probably one of the defining characteristics of the way we live now. It corrodes kindness and is the antithesis of creativity. I don’t think people who bicker leave themselves enough energy to want to be godly. The character motivations, then, are sometimes selfish.

The scene that you quote from is an “ancient aliens” chapter. There’s a high priest atop a pyramid during a solstice, and so it’s a big celebration and the people have come out. A UFO appears above the pyramid and leaves a message like the one our contemporary characters witnessed, except the ancients can read the hieroglyphs. However, the sky letters are three dimensional, so they spell something different for the priest, because he’s got a different vantage point (like the carved wooden blocks on the cover of the book Gödel, Escher, Bach that project different shadow-letters depending on the source of light). The people on the ground see a message of peace while the priest on the pyramid sees a demand for a sacrifice.

I don’t think the priest wants to be godlike either. I believe priests know their flaws very well. It’s enough for them to be in a position to interpret God’s message. It’s enough for them to be in a position to never sacrifice the children who come from wealthy families. We still have these kinds of people among us: interpreters of the divine and proximity playas. As for any hypothetical message, there’s room for miscommunication, always.

Chapter 16: Which writers (and/or readers) did you have in your head as you were writing Message in the Sky?

Minichillo: Steven Spielberg? I wanted to write an updated Close Encounters.

In literary science fiction, my favorite stuff in recent years has been short stories. Ted Chiang’s “The Story of Your Life” that the film Arrival was based on imagines E.T. > human communication, and it’s brilliant. Ken Liu is another sci-fi short story writer I’m in awe of. I’m not trying to write like them, but I see them as setting the bar.

Chapter 16: How do you perceive the interplay between the normal and the perverse? In what ways does this express itself in your fiction?

Minichillo: For most of us, what’s “normal” is familiar and comfortable, but it’s also low-achieving, unaspiring, and common. Satire ridicules normalcy. It hates ignorance and so do I.

Chapter 16: You were an English professor at Tennessee Tech and now teach writing at TSU. How does teaching influence your work as a storyteller?

Minichillo: I’ve taught English at several area universities and colleges: research writing, literature, and creative writing. I’m immersed in the subjects of literature and writing, and I’m around smart young people. It keeps me sharp. As a reader, I want to spend time with writers who are sharp.

Chapter 16: What is a book you read over and over again?

Minichillo: I’m a big fan of novellas: The Death of Ivan Illych, The Dead, Death in Venice…

That makes it sound like I’m interested in death when really I’m interested in Modernists.

Sarah Norris has written about books and culture for The New Yorker, San Francisco Chronicle, The Village Voice, and others. After many years away, she’s back in her hometown of Nashville.