In Praise of Regulation

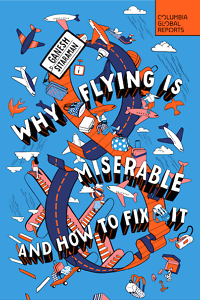

Ganesh Sitaraman explains how to fix flying

Ganesh Sitaraman feels your pain, at least when you’re trying to get somewhere and your flight keeps getting delayed. In Why Flying Is Miserable and How to Fix It, the Vanderbilt University Law School professor details how the airline industry has gone awry and what can be done about it.

“Tens of thousands of flights are delayed and canceled each year,” Sitaraman says in the book’s introduction. “We’ve missed weddings, had our vacations shortened, lost time with friends and skipped important meetings. … We pay extra to check our bags and then worry that they’ll get lost. The overhead bin space seems to shrink every year — just like the amount of leg room.”

“Tens of thousands of flights are delayed and canceled each year,” Sitaraman says in the book’s introduction. “We’ve missed weddings, had our vacations shortened, lost time with friends and skipped important meetings. … We pay extra to check our bags and then worry that they’ll get lost. The overhead bin space seems to shrink every year — just like the amount of leg room.”

He goes on to familiar complaints about higher prices, hours waiting on the tarmac, missed connections, and rural areas without any airline service at all. There are also unnecessarily complex point systems and perks you can only get with a particular credit card.

Surveying the multitude of problems is easy. Next comes an analysis of how we got here and the best way forward. To his credit, Sitaraman bangs that out in a zippy 170 pages, somehow making the wonky part of the story understandable, even gripping at times.

“We don’t have to accept this state that we’re currently in, where flying is so miserable,” Sitaraman said in an interview with Chapter 16. The conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Chapter 16: This story in some ways starts in the 1970s with an approach to economics known as “The Chicago School” that turned out to be better in theory than in the real world. Put simply, thinkers like Alfred Kahn were all in on unfettered capitalism and wanted to wipe out business regulations as much as possible. Is that a fair characterization?

Ganesh Sitaraman: I think Kahn (the former chair of the Civil Aeronautics Board known as the “Father of Airline Deregulation”) was an academic who really believed in the core Econ 101 principles. The problem is [that approach] embeds a set of values that are not the only values we as a society have. We don’t just want the economy to be as efficient as possible without regard to any consequences. We care in this country about quality of life for employees and workers. We care about geographic inequality, about access to opportunity in lots of different places. Those are important values too. I think we need to have an airline policy that recognizes we have multiple values that are critically important for our country.

Chapter 16: President Reagan famously said, “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” How did that play out?

Sitaraman: I think the people pushing deregulation in the 1970s believed sincerely, but incorrectly, that airlines were just like any other industry and that traditional economic principles of competition would work in the industry. What 30 years have shown us is that was wrong. The people in the [airline] industry at the time knew it was wrong. They didn’t need 40 years of history to show them it was wrong because they understood the industry well enough to recognize what would happen. I think that should be a cautionary tale for people who are thinking about advancing policy based on economic theory without regard to how the different values we have as a country play out in the real world.

Sitaraman: I think the people pushing deregulation in the 1970s believed sincerely, but incorrectly, that airlines were just like any other industry and that traditional economic principles of competition would work in the industry. What 30 years have shown us is that was wrong. The people in the [airline] industry at the time knew it was wrong. They didn’t need 40 years of history to show them it was wrong because they understood the industry well enough to recognize what would happen. I think that should be a cautionary tale for people who are thinking about advancing policy based on economic theory without regard to how the different values we have as a country play out in the real world.

There is a lot of rhetoric around regulation. But when you ask people about specific regulations, people want them. People want rules that make sure we can have air that’s clean, that children’s toys are safe, that the food we eat is safe.

Chapter 16: What makes the airline industry different from a hardware store or any other type of business, so that it needs to be treated differently by the government?

Sitaraman: [The airline industry] is much more like a public utility or a basic infrastructure than it is like an ordinary business. Getting rid of regulations has actually not meant a highly competitive market that works extremely well, according to the tenets of Econ 101, but massive concentration and consolidation into a very small number of airlines and worse quality of service. In many cases, [the result has been] higher prices and less access to important places. These are all things we don’t want for a basic public utility that’s essential for so many communities to have access to commerce and tourism, transportation, and the wider world.

Chapter 16: What other industries are treated like utilities?

Sitaraman: Airline regulation is a subset of an American tradition of regulated capitalism that goes back generations. In many sectors … like transportation, energy, telecommunications, and banking, a system of structural regulation governed the industry to make sure it was serving the public instead of becoming exploitative and monopolistic. That system worked pretty well. Deregulation starting in the 1970s or thereabouts came for all of these industries and sectors. In many of these sectors, we now have crises. Think about railroad or maritime shipping during COVID, or the financial crash and bank failures. [In 2023] there was conversation about the lack of access to broadband internet in rural areas. These are all places where we’ve had real challenges, in part because these sectors were not subject to real regulatory requirements that would ensure stable, reliable service to the country.

Chapter 16: In addition to poor service, the airline industry has needed to be bailed out by the government during bad economic times. Why is that?

Sitaraman: I think people are upset … that the airlines really entered after deregulation into a kind of boom and bust cycle, where there are some years where they’re making money hand over fist. Then there’s a big demand shock, like September 11 or COVID, and they come to Congress asking for taxpayer support and bailouts. Congress has to oblige because the airlines are too important to fail. … If all the airlines are going to shut down, or lay off tens of thousands of workers, that is a national problem. It’s a problem for our entire economy and our whole country. So we have to rescue them. But if we have to rescue them, it proves this is an industry that gets massive privileges from us, the country, and therefore should have some obligations too.

Chapter 16: In a perfect world, how would the airline industry be fixed?

Sitaraman: In the book, I outline three principles for reforming airlines. First, no more flyover country. We need an airline system that reaches all different parts of the country, including smaller cities and midsize cities, not just the largest cities. Second is no bailouts, no bankruptcies. I think we need an airline system that is stable and reliable, that doesn’t require coming to taxpayers for support when there are demand shocks. And third, fair and transparent pricing. I think it’s gotten way too complicated for consumers. There are a lot of ways we can get to these different principles. I outline a number of them in the book. But that’s where I think we should be pointing … to solve these problems.

Chapter 16: What can an average person do about this?

Sitaraman: We don’t have to accept this state we’re currently in where flying is so miserable. The first thing people need to do is to call their members of Congress and tell them to get to work on fixing this industry and making it more resilient and making the flying experience better for customers. … We need to have a system where regulations are designed well to do the things we want them to do. Regulation itself isn’t inherently good or bad. It’s just a tool we can use to accomplish policy goals. It’s the same way that laws themselves aren’t inherently good or bad. Good laws are good and bad laws are bad.

Jim Patterson is a freelance writer in Nashville. His work appears regularly on the United Methodist News website, UM News. He formerly covered country music for The Associated Press and was a public affairs officer and senior writer at Vanderbilt University.