Hope Is the Thing

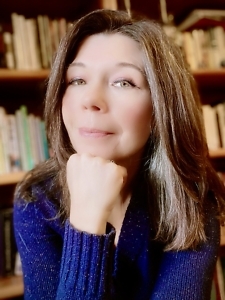

Poet Danita Dodson reflects on the loss of her father

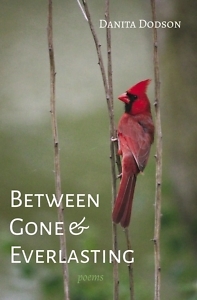

Danita Dodson’s most recent collection of poetry, Between Gone and Everlasting, explores the many facets of grief after the loss of a parent. Dodson focuses on the death of her father and discusses grief and its impact across all facets of her life. The voice of the collection is childlike and hopeful, conveying a reverence for the dead and the process of dying and grieving, as well as a love for the natural beauty of the world and the signs of life below the surface. Dodson’s collection captivates with its focused narrative arc, using the extended theme of grief to tell a story of one man’s life and one family’s reaction to the loss of that life.

A resident of Sneedville, Tennessee, Dodson is the author of two previous collections, Trailing the Azimuth (2021) and The Medicine Woods (2022). She answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

A resident of Sneedville, Tennessee, Dodson is the author of two previous collections, Trailing the Azimuth (2021) and The Medicine Woods (2022). She answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: Your new collection is dedicated to your father who died in 2022. Can you discuss the journey between navigating your grief and writing the poems in this collection?

Danita Dodson: When Daddy passed suddenly, I couldn’t imagine what a world without him would look like, let alone describe it. For once, I was at a loss for words. Though giving voice to grief through poetry ultimately became a vital part of the process of nurturing myself in the ensuing months, it didn’t happen right away in any planned way. In fact, at first, I was too numb to write anything. Then, little by little, a word or two, a phrase, or a line visited me. I honored these poetic gifts of grief by jotting them down but wasn’t yet ready for what poet Rita Sims Quillen told me is the “deep cut that going there is.”

What I did was write my father’s biography. A week or so before he passed, he had hinted to me to write about him. At the time, I was working on a 200-year family history of his paternal lineage and had reached exactly the point of relating his story. Sifting through various documents, left-behind tools, and other remnants of his life in the months immediately following his death, I started writing about the multifaceted man he was. It was like looking at him anew through a kaleidoscope, piecing him back together through vignettes of memory. This journey of rediscovering him in the remains of history, in essence, parented the creative process. The poems started coming to me from all sorts of angles, lines, and forms.

Chapter 16: In the poem “Stark Shock of Summer,” you write about how the weeds in the garden are “reminding me of the things / that grow out of our hands, / that become too large to hold — / like grief.” How has your experience writing on grief changed or evolved over the course of your career?

Dodson: I’ve given voice to grief before. It’s part of the human experience, so sometimes there’s no way around it when writing. In the “Pandemic Pathways” section of Trailing the Azimuth, I’ve written poems expressing the speaker’s grief in the throes of the worst days of COVID-19. And in The Medicine Woods, my collection of eco-poetry, I’ve written about environmental grief born from a keen awareness of climate change and the other violences that humans visit upon the Earth and each other.

Dodson: I’ve given voice to grief before. It’s part of the human experience, so sometimes there’s no way around it when writing. In the “Pandemic Pathways” section of Trailing the Azimuth, I’ve written poems expressing the speaker’s grief in the throes of the worst days of COVID-19. And in The Medicine Woods, my collection of eco-poetry, I’ve written about environmental grief born from a keen awareness of climate change and the other violences that humans visit upon the Earth and each other.

With all that said, I do feel that my experience writing on grief has evolved profoundly. In the first two collections, while the voice in the grief poems articulates connection and empathy and mourns the broken, the speaker is someone who looks in upon the pain of the world as though through a window, so there is still a bit of a barrier. In Between Gone and Everlasting, the barrier is shattered, and the window is wide open to the experience and expression of grieving. To write about the harrowing loss of my father, I had to pull up a chair close beside grief itself and sit with it for a long time so that the words I wrote were authentic. The process was hard but also beautiful and healing. I found myself in a liminal space, or a thin place, where I participated in a type of conversation with my father as I wrote. Writing grief became more personal and poignant than it had ever been before. I think readers can see the difference.

Chapter 16: Many of your poems use a first-person perspective. Can you discuss your experiences and interactions with people (fans, colleagues, family members) who automatically assume the “I” in your work is always yourself?

Dodson: It’s true: Some readers automatically assume the “I” is the confessional voice of the poet. I’ve encountered this assumption often when teaching literature. On student poetry analysis papers, I’ve frequently noted, “Don’t just assume the persona/speaker/voice in a poem is the poet.” Poets write from a broad understanding of the human experience. As “makers” or “shapers,” we sculpt a voice in each poem who is really a character or a “new” person. Poetry isn’t exactly nonfiction, and not every word is 100% personalized even if seen through an autobiographical lens.

However, I also tell them not to overlook the fact that poets might choose to write from some deep personal experience or cultural perspective. Some of the world’s greatest writers have written their greatest works from such places. Know the difference between the created and the creator, and also allow for poetic license. In Between Gone and Everlasting, especially in the “Whippoorwill’s Call” section, which is intense in its various depictions of grief, I do use first person to describe my own grief experiences, yet the speaker is also not me but a voice I’ve created who is grieving like I am. Also, the lens of memory, which is by nature a “retelling,” fictionalizes the voice in a way. Another thing occurs in some of the poems in this collection, and it exemplifies the poet’s ability to shape the voice: The “I” is sometimes the voice of a departed father speaking, or even the past itself.

Chapter 16: The voice in many of your poems in Between Gone and Everlasting is childlike, innocent, and full of wonder for the natural world. How do you manage to maintain a consistent voice across different poems in a collection?

Dodson: It took a bit of work to keep the consistency, especially given the diversity of style and range of subject matter. Since I wrote from the viewpoint of a persona who rolls back the years to recollect a departed father, capturing that childlike voice of innocence and wonder was important to me. Also, because I wrote in the liminal space of imagination where the bereaved can commune with the departed in a thin place of remembering, it felt necessary to mirror a youthful voice who recognizes that remarkable things can happen in the spirit world and in the world of memories. Grief is hard, but since it is a brand-new experience for the bereaved, especially the speaker who is now parentless, it causes one to basically feel like a child learning to talk again.

I tried to lace together images throughout the poems that underscore what it is like to be filled with wonder when one least expects it, such as the awe of seeing a sunrise or the epiphanic experience of remembering a departed father. In “Meditations in a Study,” the speaker meditates on a photo of a “a fat-faced infant / with a headful of dark, curly hair, / five months old, laughing at life.” It was this image that I kept in my mind as I wrote about the love of, and for, a father that is as pure as it was the day he first held her as a baby. Maintaining that voice was also a way of creating poems that, in essence, “become the parent who listens and comforts” (in the words of one reviewer).

Chapter 16: Many Tennessee poets are categorized as pastoral writers. What are your thoughts on this categorization, and where do you see your work in the mix?

Dodson: Author Tim O’Brien says, “All writers must revisit terrain.” Let’s face it: Many Tennessee poets revisit the natural landscape and the rural countryside of our state in their works. The land and a sense of place seem, in part, to define who we are as people and as writers, whether we live in and write about East, Middle, or West Tennessee. To ignore rurality is to ignore part of who we are. However, to use a cookie cutter to typify Tennessee poets as simply portraying the bucolic is to disregard the complexity of the representation of the land that occurs sometimes in their works, which might incorporate, for example, the realism of labor, immigration, or even climate change.

Also, often the urban and the rural blend together, skyscrapers and corn fields inhabiting the same horizon. The Medicine Woods projects the wisdom of a voice with a deep connection to the rural landscape who describes its damaged spaces, protests its destruction, fights for its protection, and saves its stories. So nostalgia for the past becomes a key metaphor and vehicle for keeping the future, also something we see in literary modernism. Though it is often looked down upon as being overly sentimental, Tennessee pastoral poetry is really a capacious category that includes many different attitudes toward rural people and rural life. Between Gone and Everlasting indeed falls in this mix because it taps into the pastoral’s recognizable ability to generate in its readers certain feelings about rural life, such as the sadness at the loss of people and places.

Chapter 16: You personify grief in different ways in this collection. If you had to give grief a physical, anthropomorphic form, what would grief look like to you?

Dodson: That’s an interesting but significant question because grief really does seem larger than life. It feels so corporal, like it is another person who sits in the room with the one who grieves. But to me, grief is not necessarily a grim reaper; it’s not monstrous, phantom-like, or dark-spirited in form. In my opinion, grief also breathes the air of beauty, since mourning comes from a deep place of love for the departed. If you allow yourself to sit with this “grief person” long enough, you’ll learn something from the loss, and that’s what I try to echo throughout the collection.

You’ll recognize grief’s wisdom, which can lead you to create something in the midst of pain. In this way, I feel inclined to give grief the form of an old quilting grandmother. She’s sagacious, creative, and loving, but her needle jabs with pain and truth too. She sits quietly until you are ready to watch her stitch her words into you. She can lead you to make something new from all the miscellaneous bits of memory and pieces of pain. The poem “Threads” is connected to this thought. But I’d also add this to my envisaged humanlike shape of grief: She would be a quilting grandmother who has wings, mystically flying in and out of view as unannounced as a bird, butterfly, or dragonfly. I often use the image of wings in these poems to show that “love outflies the edges of life and death.”

Abby N. Lewis is from Dandridge, Tennessee. She is the author of the full-length poetry collection Reticent and the chapbooks This Fluid Journey and Palm Up, Fingers Curled.