Strangers on a Train

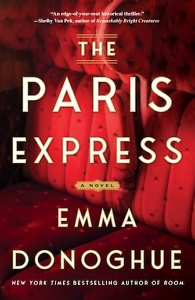

In Emma Donoghue’s The Paris Express, passengers hurtle toward a catastrophic future

An express train traveling from Normandy to Paris was, in 1895, an embodiment of modernity. In Emma Donoghue’s new novel, The Paris Express, the train, touted as the fastest transportation in the world, represents a melding of mechanical and social engineering, an invention that is changing the face of the nation. Though the train is divided along class lines into separate compartments, all of the passengers “will be treated to the luxury of speed.” On this trip, however, they are charging into disaster.

Donoghue’s story hews closely to the historical facts of a famous derailment on October 22, 1895, during a time of upheaval in France when ideological conflict and technological advancements disrupted the old order. Readers who see the parallels between that time and ours are primed to enjoy this novel. The route from Granville to Montparnasse Station, scheduled for just over seven hours, is part of a nationwide network that is shrinking the country and facilitating mass migration.

The train’s passengers reflect other imminent changes. Alice Guy, a “strikingly pretty” secretary to a camera manufacturer, urges her employer to capitalize on the potential of motion pictures. A young scientist, Marcelle de Heredia, types up lecture notes on a portable typewriter that enables her to work anywhere. Transportation, entertainment, efficiency — the 20th century beckons.

Not everyone onboard is sanguine about the social benefits of these inventions. France’s economic expansion has, paradoxically, narrowed the prospects of the working class. Donoghue captures the attendant unrest in a young anarchist, Mado Pelletier, who has read enough Marx to know that in capitalism human life is reduced to its economic value, which drops as the worker ages and can be made obsolete by technological innovation. Mado has learned “how the machine of the world chugs on and how no fiddling little adjustments will ever fix it.” Instead, France needs to be shaken into awareness by acts of destruction. Mado brings a homemade bomb on the train; she is prepared to sacrifice herself in the war against the ruling class.

Riding in the more exclusive cars, conservative politicians discuss the growing anarchist movement — 2,000 members in Paris, per one estimate — and how to stop it. In Donoghue’s telling, powerful men simultaneously profit from technology and fear the social turbulence it causes. They are deaf to the rhetoric of the “communards” and conspire to retain the control their families have accumulated over generations. While they sip Bordeaux and nibble on lamb in first-class carriages, the working-class stiffs crowd into steerage and eat stale bread while complaining about fat cats. The ambience of violence permeates every conversation. The whole country is ready to explode.

In terms of plot, Donoghue faces the challenge of creating tension in a story that readers know ends in disaster. In an author’s note, Donoghue includes a contemporary photo of the train having fallen off the elevated tracks in Paris and resting nose-down on a couple of unfortunate store fronts. Donoghue builds excitement by focusing on Mado, detailing her thoughts (and second thoughts) about detonating a bomb on a train filled with children and a pregnant woman. The author also gets inside the mind of an older passenger, a Russian émigré named Blonska, who intuits Mado’s plan. Can Blonska find a way to get the bomb off the train without killing them all?

In terms of plot, Donoghue faces the challenge of creating tension in a story that readers know ends in disaster. In an author’s note, Donoghue includes a contemporary photo of the train having fallen off the elevated tracks in Paris and resting nose-down on a couple of unfortunate store fronts. Donoghue builds excitement by focusing on Mado, detailing her thoughts (and second thoughts) about detonating a bomb on a train filled with children and a pregnant woman. The author also gets inside the mind of an older passenger, a Russian émigré named Blonska, who intuits Mado’s plan. Can Blonska find a way to get the bomb off the train without killing them all?

Donoghue’s profound triumph is her depiction of the broad array of passengers, whom we don’t see as victims but as heroes of their own stories. A shy American artist becomes mesmerized by scientist Marcelle de Heredia but struggles to start a conversation. When an accident initiates their interaction, Marcelle reveals that she was inspired to pursue science by the drowning death of her younger brother. “I needed to know what the difference was between my brother after and before. What makes a body lie inert or move,” she tells the artist.

The novel, whose chapters mark the train’s arrivals and departures, rotates among the minds of a dozen characters, including a surprising one: the train itself. Engine 721, referred to as “she” by the engineer and crew, sniffs out Mado’s intentions but “doesn’t take it personally. She is made of wood and metal, and her temperament is stoic.” The train’s moods and needs alter with the landscape. Like the crew that drives her, she feels the pressure to reach Paris on schedule, an urgency that could become as dangerous as the anarchist’s bomb.

The Paris Express is a short novel but isn’t hurried. Donoghue takes time to develop each character, a compassion that intensifies the stakes as the train nears Montparnasse. Though set in fin de sicle France, a period that gave birth to the modern, this novel demonstrates the classical literary virtue of sympathy. Donoghue makes us cheer for the happiness of her characters as they speed inexorably toward disaster.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.