The Scientist’s Dilemma

Brilliant women struggle to be heard in Aristotle’s Wife

“If I want people to listen, I need a Y chromosome,” says Barbara in Claudia Barnett’s short play I Knew She Was Right. Inspired by geneticist Barbara McClintock, who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology in 1983, this play is one of six in Barnett’s remarkable collection Aristotle’s Wife, based on unsung women in science.

Not only are the women unsung, they are dismissed, robbed, overshadowed, and generally disdained by the male-dominated field. And so it goes through history in more fields than you can shake a stick at. But we are told the word scientist was created (maybe reluctantly) to allow women entrance into scientific disciplines when previously one would say “a man of science.”

Barnett, a professor of English at Middle Tennessee State University and a working playwright, makes each play in the collection a complete world, an imagined moment in the women’s lives. The pieces can stand alone, but the book’s publicity copy states, “These plays can be performed together as an evening of theater for smart audiences.” Smart, indeed. As is the crisp dialogue, the barriers the protagonists experience, their drive to create and discover, their renegade behavior (cigarettes! trousers!), even their wry humor. The plays are steeped in the hard truths of history yet imbued with theatricality.

In Almost Certainly Not Real, for example, Barnett says in her notes: “I picture this play as a movement piece, perhaps a dance, in which the characters grow farther apart.” A dance is perfect for this two-woman piece, their push and pull like the gravitational force in our heavens. Inspired by astronomer and astrophysicist Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, Barnett’s Cecilia faces the terrible choice of undercutting her dissertation’s conclusion or facing professional failure. Saying that the sun and stars are made of hydrogen and helium is simply a bridge too far in 1920s (male) physics — so she sacrifices for the sake of publication and career, acknowledging her conclusion but adding that it is “almost certainly not real.” She becomes the first person to receive a doctorate in Harvard’s new graduate astronomy program.

The setting of these plays is often a lab table, with microscopes, beakers, or other equipment. These settings provide the fulcrum of conflict and change, but because the plays are short, around 10 minutes each, the endings don’t flow to denouement as in a full-length work, but are unexpected and ambiguous in all the best ways. We peer into a moment’s microscope slide and see a heightened universe of relationships, life struggles, missed opportunities — all nonetheless transformative. If anything, these short pieces punch deeper than a two-act play might. And, most importantly, they leave you hungry for more.

The setting of these plays is often a lab table, with microscopes, beakers, or other equipment. These settings provide the fulcrum of conflict and change, but because the plays are short, around 10 minutes each, the endings don’t flow to denouement as in a full-length work, but are unexpected and ambiguous in all the best ways. We peer into a moment’s microscope slide and see a heightened universe of relationships, life struggles, missed opportunities — all nonetheless transformative. If anything, these short pieces punch deeper than a two-act play might. And, most importantly, they leave you hungry for more.

Equally amazing is Barnett’s copious research for each woman depicted, listed in notes and sometimes quoted in the play text. Whether this history is personal or professional, Barnett slips it in subtly and naturally. This information about real women’s creative lives does not weigh down the action. Instead, it fully grounds each examined microcosm, while Barnett’s imaginings lift them into embodied flight.

Each piece here has its particular power and poignancy, but the title play, which opens the collection, may be the most disarming. We see Aristotle’s much younger wife, Pythias, at his side examining and diagraming the innards of male and female octopi. She loves their work together, creating a marine encyclopedia, sharing both mission and purpose. At one point, she produces a small bowl of blood with a bit of tissue and engages Aristotle in his own method of inquiry to identify it. She asks him to “see” what isn’t yet revealed. Though she wants to maintain objectivity and rationality and hold her own as a partner, she breaks down saying it’s her own embryo, miscarried that morning. This startling revelation becomes the thread so deftly woven through Claudia Barnett’s six plays: to see the unseen, to examine, to struggle, to wonder, and sometimes to grieve — whether in the name of science or in the name of art.

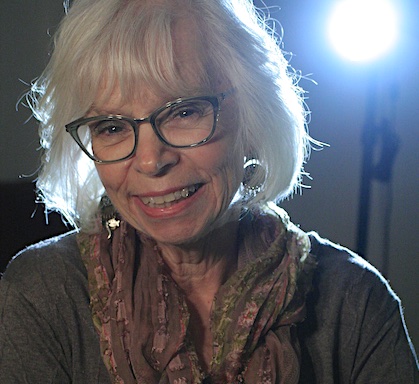

Poet, playwright, essayist, and editor, Linda Parsons is the poetry editor for Madville Publishing and the copy editor for Chapter 16. Her sixth collection is Valediction: Poems and Prose. Five of her plays have been produced by Flying Anvil Theatre in Knoxville, Tennessee. She is an eighth-generation Tennessean.