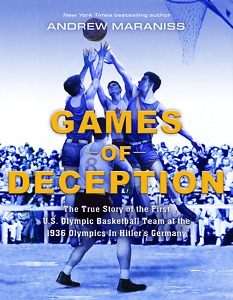

A Bright Shining Lie

Andrew Maraniss discusses his new book for young readers about the 1936 Olympic games in Berlin

Andrew Maraniss has developed a knack for topics that explore the intersection of sports and politics. In his first book, Strong Inside, he told the story of Perry Wallace, the Vanderbilt basketball player who broke the color barrier in the Southeastern Conference. After the success of that book, Maraniss stumbled on a new project when, during a visit to the University of Kansas, a friend asked, “Did you know that James Naismith was in Berlin to see his invention become an Olympic sport?” Immediately, Maraniss decided to write about the connection between the Nazi Games and the history of basketball. The result is Games of Deception.

Though Maraniss, a sportswriter who worked in Vanderbilt’s athletics department, has a background in athletics, the basketball portions of his new book fade in consequence next to the stark politics of the era. Hitler used the 1936 Games as a spectacle (“a bright shining lie,” in Maraniss’ words) to disguise the disturbing realities of Nazi Germany, particularly the systematic exclusion of Jews from the public sphere and the opening of the concentration camps. German officials made sure that Berlin’s streets were clean, its street lamps festooned with garlands, and the sports facilities immaculate. But American athletes saw behind the façade to perceive a country preparing for war.

Though Maraniss, a sportswriter who worked in Vanderbilt’s athletics department, has a background in athletics, the basketball portions of his new book fade in consequence next to the stark politics of the era. Hitler used the 1936 Games as a spectacle (“a bright shining lie,” in Maraniss’ words) to disguise the disturbing realities of Nazi Germany, particularly the systematic exclusion of Jews from the public sphere and the opening of the concentration camps. German officials made sure that Berlin’s streets were clean, its street lamps festooned with garlands, and the sports facilities immaculate. But American athletes saw behind the façade to perceive a country preparing for war.

From the start, Maraniss wrote this book with young readers in mind. His experience with the YA edition of Strong Inside convinced him that middle school students were avid for in-depth sports histories that expose little-known aspects of American culture. In Games of Deception, he succeeds in animating his chapters with colorful characters (such as Sam Balter, the lone Jewish player on the U.S. basketball team) and vivid anecdotes, but he never talks down to his readers. Maraniss’ diction will stretch a 12-year-old’s vocabulary (he calls the Berlin Olympics “one gigantic exercise in subterfuge”), and his descriptions of German anti-Semitism will challenge adolescent sensibilities.

Maraniss does not flinch from identifying his story’s villains — including the Americans who cozied up to Hitler. This book will appeal to readers of all ages who want to know about the seamy side of the Olympics, which are billed as promoting international harmony and good will but can be used by unscrupulous dictators to conceal evil intentions.

Maraniss answered questions from Chapter16 via email:

Chapter 16: At the book launch for the young adult (YA) edition of Strong Inside, you announced that your next project was going straight to the YA audience. What motivated you to make that decision?

Chapter 16: At the book launch for the young adult (YA) edition of Strong Inside, you announced that your next project was going straight to the YA audience. What motivated you to make that decision?

Andrew Maraniss: The experience of telling Perry Wallace’s story to students around the country had a profound and unexpected impact on me. I was moved by the way students responded to that book, by their passion for reading, and by their thirst for books about race, equality, and justice. It’s pretty remarkable to look at the books young people are reading these days, and the nuanced and empathetic understanding of the world that they are developing, and to contrast that with the reactionary, bigoted and uninformed discourse coming from some corners of our society. Kids are light years ahead.

Just as important, I met a lot of kids — usually athletes — who told me that they hadn’t really enjoyed books until they read Strong Inside. There’s not much narrative nonfiction for kids, especially related to sports. My goal is to continue writing serious sports-related nonfiction, with a social justice bent, for young readers. Casting these stories within the realm of sports is an accessible way to introduce themes with larger social significance. If my books can help inspire students to read and can help them think about their place in the world in a different way, the opportunity they have to stand up against injustice rather than remaining a bystander, that’s a very gratifying thing. I hope that adults will read these books, too. Adults love YA fiction. Why not nonfiction? Games of Deception is just shorter than a typical book for adults. But with attention spans and free time shrinking, that may be ideal for a lot of people.

Chapter 16: Games of Deception covers a lot of history — the rise of Hitler, the invention of basketball, the worldwide spread of the sport — that requires substantial background research (as your extensive bibliography attests). How do you know when you have enough material? What keeps you from disappearing down these historical rabbit holes?

Maraniss: I don’t necessarily mind disappearing down some historical rabbit holes during the research phase, as long as I don’t spend too much time there when I’m actually writing! I love visiting archives and libraries, reading books and old newspaper articles, conducting interviews. Spending the time to do the research properly is the most important part of writing good narrative nonfiction. It gives you the freedom to then tell a story in a vivid and interesting way. First you need to uncover the details. For this book, there were certain places I knew I had to visit: Springfield, Massachusetts, where James Naismith invented basketball; McPherson, Kansas, the small town where half of the first U.S. Olympic basketball team came from; and the University of Illinois, home of the Avery Brundage archives. I interviewed as many descendants of the U.S. basketball players as I could find. I spent a little over six months on the research before I started writing. I only had a year to research and write this book, which was far different from Strong Inside, which took me eight years.

Chapter 16: James Naismith and Phog Allen, two pivotal figures in basketball’s origin story, emerge as noble figures in your telling. To your mind, which unsung character from Games of Deception is the most inspiring? (My vote is for Sam Balter.)

Maraniss: I went to Cincinnati to visit the American Jewish Archives. As I was leaving after a day of research, one of the archivists mentioned that there was a 95-year-old Holocaust survivor living in Cincinnati who had attended the 1936 Olympics. I scheduled a return trip and met the man, Dr. Al Miller. He had been a 13-year-old Jewish kid in Berlin at the time of the Olympics. He told me stories about sneaking into the Olympic Village to see all the athletes and about watching Jesse Owens, the first black man he’d ever seen, win a gold medal. He told me how he escaped from Nazi Germany in 1937, unsure if he’d ever see his parents again. And he told me about how he visits with schoolchildren now and talks to them about the rise of the Nazis and about the Holocaust. I asked what he tells kids about how they can prevent fascism from taking hold in the United States. He said the kids already have the answer. They say it every morning with hands over their hearts — the last five words to the Pledge of Allegiance. The key, he said, is ensuring “liberty and justice for all,” with an emphasis on “all.” Finding Dr. Miller gave me a way to tie past to present, so he emerges as an interesting and unexpected character in the book.

I’m glad to hear you liked Sam Balter! He was a fascinating character, the only Jewish member of the U.S. basketball team. His daughter wrote a fun book about him, and his granddaughter works for NPR. They were both very helpful as I researched this book. Balter went on to host a national sports radio show that was essentially a precursor to ESPN SportsCenter before the days of sports on television. I would have loved to have met him.

Chapter 16: Avery Brundage, the president of the American Olympic Committee, certainly has critics among historians of the Olympic movement, but in your book he comes across as downright sinister. What do you hope your readers (young and old alike) derive from your depiction of Brundage and his supporters?

Maraniss: Brundage was a bigot in an important leadership position who purposely misled the American public about the Nazi regime and portrayed his critics as un-American. He worked with the Nazis behind the scenes to influence public opinion in the U.S. He had personal financial motivation to cooperate with the Nazis because his construction firm was contracted to build a new German embassy in Washington, D.C. He removed James Naismith’s name from the pass list for the Olympic basketball tournament — temporarily leaving the inventor of the game stranded outside the venue until other officials came to the rescue. Brundage is clearly one of the most significant figures in the history of the Olympics, but I didn’t find him to be a particularly honorable person. I want young readers to understand the power of bad leadership. One man’s bigotry and greed had enormous international consequences.

Chapter 16: Opposing Brundage were athletes, politicians, and clerics who called for the U.S. to boycott the 1936 Olympics. In your opinion, how might a leader more enlightened than Avery Brundage have handled the conflict?

Maraniss: There was room for an honest debate on whether we should have boycotted the Olympics. Public opinion on the matter was split. Boycott proponents pointed to the human rights abuses in Germany and asked how a competition based on sportsmanship and fair play could rightly take place there. Most athletes, even African American and Jewish ones, wanted to participate. They felt the best way to disprove Hitler’s views on Aryan supremacy was to go to Berlin and win. They also had their own self-interest in mind — they were world-class athletes who simply wanted to fulfill their dreams of competing in the Olympics. So, there were fair arguments on either side.

A more enlightened leader would have encouraged a truthful debate. Instead, Brundage went to Germany on a sham of a fact-finding mission where he enjoyed the company of his Nazi hosts and then had his Nazi friends send news articles to American media about “positive” things happening in Germany to counteract news of Nazi atrocities that were reaching the U.S. He claimed that sports and politics should not mix, but nobody was using sports to their political advantage more than Hitler. Brundage developed a major PR campaign that painted boycott supporters as disloyal Americans. Of course, how could an American who opposed Hitler’s assault on humanity, democracy, religion, and truth be considered disloyal? Brundage’s narrow worldview was dangerous.

Chapter 16: Readers expecting Games of Deception to portray Americans as white-hatted heroes fighting Hitler’s evil empire will be surprised. You are unflinching in your account of the racism experienced by minorities in the U.S. of the 1930s. What do you hope young readers will glean from your comparison of Hitler’s Germany and America during segregation?

Maraniss: Some people might read your question and think that I write that Hitler’s Germany and America during segregation were the same. That’s not true, but it is equally untrue to only go the “white-hatted hero” route. Often, young readers’ understanding of this era in history is limited to World War II itself. Or they learn about Jesse Owens and how he disproved white supremacy through his heroics on the track.

But when the American Olympic Committee produced a book recapping the highlights of the Games, Owens’ picture wasn’t even included among the U.S. gold medalists. When he returned to the U.S. after the Olympics, his wife wasn’t even allowed in some of the venues where he was honored. He couldn’t find work and was reduced to exhibition races against horses to make some money. Congress couldn’t even pass a federal anti-lynching bill because racist Southern senators opposed it. Mexican Americans were deported from California by the tens of thousands in the early 1930s. At the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles, athletes from Mexico and Japan weren’t allowed to eat at local restaurants that served other Olympians. Many Americans supported our participation in the Nazi Olympics because they didn’t really have a problem with Hitler at that time. Avery Brundage received plenty of letters of support. It’s important that young readers — or anyone, for that matter —learn this because it’s simply the truth. The only way to identify, resist, and fix similar problems in our own time is to acknowledge and learn from the injustices in our past.

Chapter 16: Readers will be moved by your account of Berlin Jews whose lives were upended by the Nazi regime. Why are their stories essential to your account of the 1936 Olympic basketball team?

Maraniss: I think it’s important in any narrative nonfiction to locate the story within a specific place and time, vividly depicted. This is not just a book about the scores of basketball games or the statistics of basketball players. The title of the book alludes to the fact that the entire 1936 Olympics were a fraud and a façade. Hitler intended to present — and largely succeeded in presenting — an image to the world that all was well in Germany. Many visitors came away marveling at German nationalism, efficiency, and hospitality. But it was all a grotesque lie. Sharing the stories of Berlin Jews was an essential part of telling the truth, a truth the fascists tried to hide from the world.

Chapter 16: In addition to covering the relevant history and politics of the era, Games of Deception is a book about basketball, covering the beginning of the full-court press and the first use of “dunk” in print. What is it about basketball that draws you to the sport?

Maraniss: I’m a fan of just about any sport. When I was a kid, I learned how to read by examining the backs of baseball cards. I started a sports magazine when I was 13 (I was the only one who read it) and came to Vanderbilt on the Fred Russell-Grantland Rice sports writing scholarship. I fell in love with watching basketball games at Memorial Gym. My wife and I had our rehearsal dinner there the night before our wedding. So, I’m just as big a sports nut as I am someone who’s interested in history and books and writing.

With this book, I was intrigued by the idea that we pretty much know the moment when basketball was invented and the date of the first-ever basketball game. And then, 45 years later, the inventor of the sport gets to see basketball make its Olympic debut. One man’s idea for a sport, which he based on a childhood game he played with rocks and boulders as a kid in rural Ontario, becomes one of the most popular sports in the world. And the “degrees of separation” from the invention of the game to today’s stars is also fascinating to me. James Naismith coached Phog Allen, who coached Adolph Rupp, who coached Pat Riley, who signed LeBron James. Three people between Naismith and LeBron!

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.

Julie Dennis.jpg)