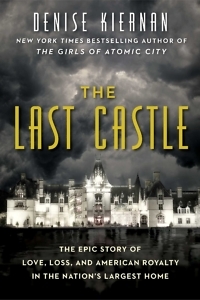

A Castle on a Mountaintop

Denise Kiernan tells the story of building the Biltmore

In the late 1850s, Frederick Law Olmsted and his partner, Calvert Vaux, transformed a remote stretch of (then) upper Manhattan, sculpting pastures and granite boulders and shanty towns into one of the world’s most iconic public spaces: the 843-acre Central Park. A decade later they unveiled Brooklyn’s smaller counterpart, Prospect Park, which many landscape architects consider their masterpiece: pastoral meadows and dense woods, miniature waterfalls and moss-fringed brooks, rock-ribbed ridges and secluded dells, all artificial. These iconic parks—New York’s lungs, as they’ve been described—have cemented Olmsted’s reputation as an American genius.

Late in his life, Olmsted was summoned to an equally grand vision far from the coastal plain of New York: the lush, shadow-dappled mountains of western North Carolina, near Asheville. George W. Vanderbilt, scion of the wealthy shipping and rail dynasty, had grown up in a vast, block-wide mansion on Fifth Avenue. A bookish, frail man and the youngest in a large family, he showed no interest in his family’s myriad businesses. Instead he sought retreat in literature and art, yearning to create a European-style château (and accompanying village of serfs) on a sprawling estate. He funneled his fortune into Biltmore, named after the Vanderbilts’ ancestral town in the Netherlands, buying up parcels of cheap and not-so-cheap land—over 100,000 acres.

Late in his life, Olmsted was summoned to an equally grand vision far from the coastal plain of New York: the lush, shadow-dappled mountains of western North Carolina, near Asheville. George W. Vanderbilt, scion of the wealthy shipping and rail dynasty, had grown up in a vast, block-wide mansion on Fifth Avenue. A bookish, frail man and the youngest in a large family, he showed no interest in his family’s myriad businesses. Instead he sought retreat in literature and art, yearning to create a European-style château (and accompanying village of serfs) on a sprawling estate. He funneled his fortune into Biltmore, named after the Vanderbilts’ ancestral town in the Netherlands, buying up parcels of cheap and not-so-cheap land—over 100,000 acres.

As Denise Kiernan recounts in her evocative, meticulously researched new nonfiction book, The Last Castle, Biltmore was shaped by Olmsted and leading architect Richard Morris Hunt. After a decade’s gestation, it became the largest private residence in the U.S., a museum (some might say mausoleum) of George Vanderbilt’s tastes and pretentions, adroitly managed by his society wife, Edith Dresser Vanderbilt. The final tally: 250 rooms, including thirty-three bedrooms, forty-three bathrooms, three kitchens, and a 780-foot-wide façade, for a grand total of 175,000 square feet, almost twice as large as Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California.

As Denise Kiernan recounts in her evocative, meticulously researched new nonfiction book, The Last Castle, Biltmore was shaped by Olmsted and leading architect Richard Morris Hunt. After a decade’s gestation, it became the largest private residence in the U.S., a museum (some might say mausoleum) of George Vanderbilt’s tastes and pretentions, adroitly managed by his society wife, Edith Dresser Vanderbilt. The final tally: 250 rooms, including thirty-three bedrooms, forty-three bathrooms, three kitchens, and a 780-foot-wide façade, for a grand total of 175,000 square feet, almost twice as large as Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California.

The author of the bestselling The Girls of Atomic City, a cultural history of the women who worked at the Oak Ridge project during World War II, Kiernan brings a deft eye for detail and observation to a very different kind of story. She conjures the fin de siècle of American’s wealthiest families, who migrated back and forth from New York to summer “cottages” in Newport, Rhode Island, to leisurely sabbaticals in London and Paris. Her recreation of Biltmore’s origins hits like a flute of fine champagne while lending social context to the mansion, the opulent Palm Court at its heart, the four-story grand staircase, the artisans employed to realize Vanderbilt’s vision:

Gustavino had also recently worked with Hunt and Olmsted at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago . . . an immigrant arriving in America for the first time would likely encounter Richard Morris Hunt’s work at the base of the Statue of Liberty and stand beneath Gustavino tiles at the Great Hall of Ellis Island . . . Their works were not relegated solely to the private dwellings and secretive salons of the wealthy, but were intrinsic elements of spaces through which all walks of people passed.

The Last Castle is Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence sprung to life—Wharton herself makes a cameo appearance—and Kiernan is occasionally overcome by the perfume of debutante cotillions, English-style hunts, and medieval tapestries. A child of privilege herself, Edith Vanderbilt rose to the challenge as Biltmore’s chatelaine, managing staff and children and floods even as the family’s fortune plummeted with the advent of the federal income tax, which ate into the Vanderbilt coffers. After George’s early death in 1914, following complications from an appendectomy, Edith and their only child, Cornelia, embraced public roles in philanthropy, education, conservation, and the dawn of American feminism. (Edith’s second marriage, to a senator from Rhode Island, sparked a new chapter in political activism.)

The book’s first half is its strongest—all gilt backdrop and famous guests—but the concluding chapters feel anticlimactic, drama leaking from the narrative. Edith and Cornelia kept the estate in family hands, buoyed by Cornelia’s marriage to an English lord, turning Biltmore into a tourist destination and shifting the finances from red to black.

This isn’t Kiernan’s fault: the latter years just can’t hold a Tiffany lamp to the glamour of the Vanderbilts at the height of their powers. That caveat aside, Biltmore is an ideal vessel for an exploration of our worship of affluence and social cachet, and more importantly, the American myth of classlessness. The Last Castle plumbs these themes and history with subtle insight and élan.

Hamilton Cain is the author of This Boy’s Faith: Notes from a Southern Baptist Upbringing and a finalist for a 2006 National Magazine Award. A native of Chattanooga, he lives with his family in Brooklyn, New York.

Hamilton Cain is the author of This Boy’s Faith: Notes from a Southern Baptist Upbringing and a finalist for a 2006 National Magazine Award. A native of Chattanooga, he lives with his family in Brooklyn, New York.