A Celebration of Everything Alive and Whole

U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón on music, animals, and the chaotic joy of spring

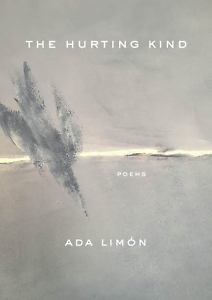

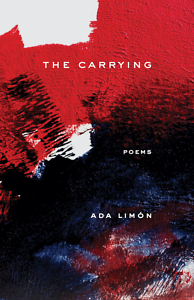

In her career as a poet, Ada Limón has been much celebrated. Her 2018 collection, The Carrying, won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry, and her work has been nominated for the National Book Award and Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award as well. She received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2020 and was named the 24th U.S. Poet Laureate in 2022. Her latest collection, The Hurting Kind, has been lauded for the way it blends the mysterious with the ordinary, the everyday with the exceptional. Her work is known for being accessible while still elevating readers, urging them into wonder and curiosity.

Limón’s poems are grounded in the physical world, delighting in robin and groundhog, horse and grackle and fox. And always there is a turn, an unexpected insight that brings together disparate things, creating a new and vital whole. The Hurting Kind draws much on the isolation and forced quietude of the COVID-19 lockdown period, but it emerges triumphant, full of life and light and shot through with hope. Her work serves as a witness and invites readers to join in the act of seeing and being seen, an idea explored in “Sanctuary,” which concludes, “The great eye // of the world is both gaze / and gloss. To be swallowed / by being seen. A dream. // To be made whole / by being not a witness, / but witnessed.”

Originally from Sonoma, California, Limón now makes her home in Lexington, Kentucky. She recently spoke with Chapter 16 by phone. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Chapter 16: How has being named poet laureate changed things for you? Are you still able to write with the same frequency or focus? Or is this a season to celebrate poetry more generally?

Ada Limón: I think it’s interesting because making poetry is inherently private on so many levels. And this is such a public role. So there is this part of me that always has to negotiate when it is time to be public, and when it’s time to be private. That was there already, of course, but this has elevated it and heightened it to a new level. There’s a part of me that sometimes gets a little divided and has to figure out when I get to be the artist, and when I get to be the performing artist, which are different things.

Overall it has really been impressed upon me how many people not only need poetry right now but are writing poetry, some people for the very first time. I think that during the isolation and grief of the chaos of the early days of the pandemic, people were looking for ways to reach out and connect. Much like bird watching became so essential to so many of us, I feel like poetry did, too. So I’m going around, and it really feels like there is a surge of energy around poetry right now that I haven’t seen before, and it feels very necessary. People are really looking to connect, and they’re looking to get healed, and it’s really powerful. It’s very emotional.

Chapter 16: The idea of making music or singing crops up frequently in your work. For example, “The Leash” asks, “Isn’t there still something singing?” and the epigraph to The Hurting Kind says, “Sing as if nothing were wrong. / Nothing is wrong.” I can’t help but wonder: Is singing “as if nothing were wrong” another definition of poetry? Do you see yourself as making music with your poems?

Limón: Unlike the incredible musicians we have both in Tennessee and Kentucky as well as all over the world, poets don’t get to work with all the music. We don’t get to have the guitarist and the bass line and the drums. We have to make all of that on the page. And so the whole poem has to be the song, and it has to have all the instruments and all the harmonies and the melodies. And I feel like when I’m writing, I’m aware of that. There is a type of singing that’s happening, and the singing is spoken, of course. But there is a level in which the musicality is high, especially in the work I’m most drawn to.

Limón: Unlike the incredible musicians we have both in Tennessee and Kentucky as well as all over the world, poets don’t get to work with all the music. We don’t get to have the guitarist and the bass line and the drums. We have to make all of that on the page. And so the whole poem has to be the song, and it has to have all the instruments and all the harmonies and the melodies. And I feel like when I’m writing, I’m aware of that. There is a type of singing that’s happening, and the singing is spoken, of course. But there is a level in which the musicality is high, especially in the work I’m most drawn to.

The other part of that is there’s a way that singing calms us, like the way you sing to a child or the way you come into communion or in community with other people. Singing together is such a powerful bond, and I think that way of making music on the page and offering something back to the world is a kind of rebellion, but also a celebration at the same time — a rebellion against everything that is suffering. But then also, a celebration of everything that’s alive and whole.

All those things are very much a part of not only who I am as a human, but who I am as an artist. You know, I always laugh because I can’t listen to music when I write, because I have to make my own. I don’t understand the idea of background music. If I’m listening to music, I’m either dancing or singing along, or I’m in it, I’m in that world. I always have to have complete silence when I write because of that. Music is very powerful and emotional for me.

Chapter 16: In both The Hurting Kind and The Carrying, the opening poems focus on a woman seeing and knowing an animal and then turning that knowing gaze back on herself — wanting to be similarly known and seen. What makes animals such an effective tool for this reflective process?

Limón: It’s true. It didn’t take me very long to realize that The Hurting Kind is a book of animals. I knew it. This is a book of animals, but it’s also about ancestors. It’s the animal ancestors, right? So much so that I remember thinking, I want to write a poem about my brother and snakes because I felt like there were no snakes. I needed to have some snakes. So I was actually making some poems based on the recognition I was in the Kingdom Animalia. I think my curiosity and my interest in them is that we just don’t know anything, and the best scientists and all of the people who work really closely with animals, they know a lot. But there is still such a mystery.

We keep finding out more and more that plants and animals are wiser and smarter than we think. No study concludes with a statement like “Oh, they’re not as fantastic as we thought.” It’s always that they really are even more so. Animals are a place for not only my curiosity and wonder and awe, but they’re also an example of how little we know of this world. I want to spend my life wondering and figuring out and being curious about animals and the human animal. So I think that I go to them because I have so many questions about them, and then at some point in there it turns on myself, and I say, “Oh, yeah, I have so many questions about you.”

Chapter 16: Your poems have been described as musical, and they are often rich with an embodied experience. I have to believe your background as a dancer has some impact in both these areas of your work. How do you see the relationship between dance and poetry?

Limón: You know, I never danced professionally, but in college I was a theater major and I took all the dance classes I could. I loved it, and I do think that both theater and dance gave me a deep understanding of the body as the artistic tool — and not just the always fluid body, right? But how do we work in a body that’s restricted?

I find those questions really fascinating, and I think it comes through in my work. That musicality and the embodiment is there, and I’m so glad to see it because I think that also there’s a level in which sometimes the body is not always the safest place, and the imagination is safer or feels more at peace.

There are times when I really call on the groundedness that the background in theater and movement gave me, and what it was to find breath when your breath was gone, or to find balance when you were thrown off-kilter but also recognizing when you yourself can propel your own momentum. Sometimes when I feel stuck, or when I feel like I’m in a sort of gray area, I can call on my body and my blood to say, “All right, let’s generate some momentum here,” and I think there’s something about making my own music on the page that was highly influenced by both of those things.

Chapter 16: It’s turning spring here, which means things are starting to green up and grow, and so much of your work deals with soil, with gardening, with growing things. And that, too, is a kind of propelling forward of your body’s actions to create.

Limón: You know, everyone loves spring, but it’s also really chaotic. And the body doesn’t know what to do with spring because we get really excited about it, but we also get a little agitated. It’s not like the lazy days of summer when you know it’s gonna be 90 again today. Instead, it’s just doing all the things all at once. And there’s an aliveness to spring that I really love. It’s one of my favorite times to write.

Limón: You know, everyone loves spring, but it’s also really chaotic. And the body doesn’t know what to do with spring because we get really excited about it, but we also get a little agitated. It’s not like the lazy days of summer when you know it’s gonna be 90 again today. Instead, it’s just doing all the things all at once. And there’s an aliveness to spring that I really love. It’s one of my favorite times to write.

Chapter 16: Well, that’s fascinating, because with The Hurting Kind being organized around the seasons, that’s the section you choose to open with.

Limón: Yeah, it is one of my favorite times to write, but I also think it presents a lot of drama. You know everyone talks about winter being dramatic, but I feel like spring is the dramatic season. It’s just doing some very, very strange things. You never know what each day is going to bring. And because of that, there’s a tension already built there in the atmosphere. Lucie Brock-Broido, who was a wonderful poet and teacher, said that she only wrote in the fall, and only with a fire going. I write all the time, I do, but spring somehow feels like an on switch to me.

Chapter 16: Do you have a garden started already?

Limón: I am going to put it in, but I have been so burned by Kentucky springs that I have seedlings getting ready, but I’m not putting them in the ground yet. Because when I’ve done it early in the past, I lost everything.

Chapter 16: In the last couple of years, when I’ve started seeds under a grow lamp, I loved watching them slowly become the thing that would go into the ground, somewhat like the way a poem can live inside of you for a while before it’s ready to take shape. How has the act of gardening or being in the natural world spoken into your work over the years? Has it changed?

Limón: Yeah. It’s funny. I think that there are years when I’ve traveled, and so I’ve planted but then never tended. And then I just see what happens. We’ll see. I’m going to plant and just see how they do. And then there have also been moments when it has become an obsession, and I want everything to be perfect, to grow the most perfect tomato you’ve ever seen, and all these things. But what I love about it is that you just can’t control it.

It’s not unlike poetry. It’s not unlike writing. You can think that you know the outcome, but in reality, nature is going to do its thing, and a poem is going to do its thing. You might think, Oh, I’m going to start out by writing this poem with this memory. And then in reality another poem happens on the page right in front of you, and you weren’t even prepared for what it was going to tell you or teach you. Often people will call what we write drafts, but to me a draft is a little more finished. So when I do workshops, especially if I say we’re going to write something in five minutes, and then move everything around, I say, they’re not drafts; they’re seeds.

Sara Beth West is a writer and reviewer, usually found at sarabethwest.com. She lives in Chattanooga with her family, dogs, and a cat who always, always, always thinks it is time for dinner.