A Connection to the Earth

Brooks Lamb works to preserve the family farm

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This interview originally appeared on June 28, 2023. It has been updated with new event information.

***

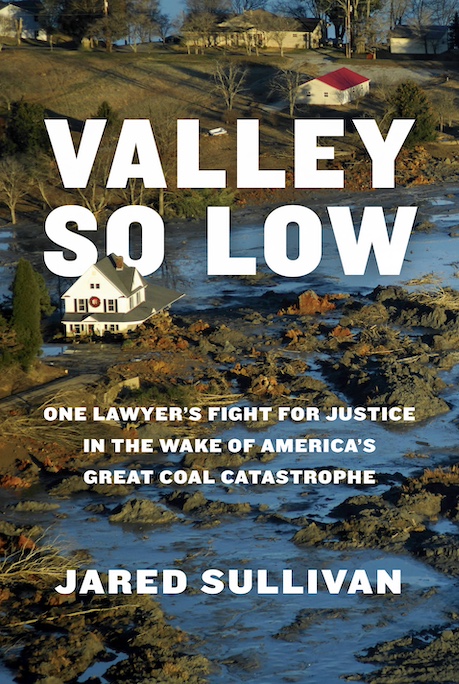

Brooks Lamb, author of Love for the Land: Lessons from Farmers Who Persist in Place, has had a heck of a week. But not an unusual week.

Lamb and wife Regan Adolph had spent two hot days cutting, baling, hauling, unloading, and stacking hay at his parents’ farm in Marshall County, about 40 miles south of Nashville. Then they headed home to Memphis to their other full-time jobs.

Lamb and wife Regan Adolph had spent two hot days cutting, baling, hauling, unloading, and stacking hay at his parents’ farm in Marshall County, about 40 miles south of Nashville. Then they headed home to Memphis to their other full-time jobs.

“We have about 25 or 30 mama cows, beef cattle there, and we raise calves off of those cows,” Lamb said. “We have a pretty substantial garden. … We’ve got a backyard flock of chickens that my parents, especially my mom, stewards.”

Lamb, a graduate of Rhodes College in Memphis and author of Overton Park: A People’s History, is a link between the family farm and academia. He earned a master’s degree from Yale School of the Environment and works as a land protection and access specialist at American Farmland Trust, a nonprofit that advances environmentally sound farming and aims to enhance economic viability for farmers and rural communities. The goal is to help farmers compete with land-hungry developers and with the large agri-business operations that Lamb says fall short in protecting the environment due to their focus on maximizing profits.

His resume and rural roots make Lamb, 29, uniquely qualified to write a book about the importance of farming in the U.S. and suggest helpful policies to support small farmers as they struggle to survive.

The following conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Chapter 16: You have a day job, help work your parents’ farm, and are hoping to buy one of your own. As someone from an urban area, that life seems very hard. Why is it rewarding to you?

Brooks Lamb: There’s something for me that is profoundly spiritual in being intimately involved with a place to take care of animals, to take care of the land itself. … There are really difficult moments, like when you’re sweating and it’s 90 degrees out and you’re itchy because you’ve got hay all over you and you’re trying to get it in the barn. Or the exact opposite in the dead of winter. That hard freeze that we had last December, going down in the barn, and being bundled up and freezing but working to feed cattle in the barn. Then looking out and seeing the cattle come in to eat and be full and happy and warm.

There’s a contentment and a joy there that’s almost indescribable for me. Some may look at that as a sacrifice. I think a lot of people look at the hard physical work of farmers and see it as drudgery. I think one can also look at it as an expression of an art form. That’s how we look at it.

Chapter 16: The author Wendell Berry comes up often in Love for the Land. What about his work attracts you?

Lamb: The first time I think I ever authentically saw myself and my family in a book was from reading one of Wendell Berry’s novels, Nathan Coulter. I remember reading it and thinking I felt seen and valued. From that moment, his writing has meant a lot to me. I moved from his novels to a lot of his essays and also enjoy his poetry, but it’s his fiction and his nonfiction essays that have moved me quite a bit. So often, you get people who write in a way where they want their readers to know that they’re smart, and they’re going to use really big words, and they’re going to use really big concepts. But Wendell writes in a way that is engaging and familiar, and I think that is one of many things that makes it really powerful.

Lamb: The first time I think I ever authentically saw myself and my family in a book was from reading one of Wendell Berry’s novels, Nathan Coulter. I remember reading it and thinking I felt seen and valued. From that moment, his writing has meant a lot to me. I moved from his novels to a lot of his essays and also enjoy his poetry, but it’s his fiction and his nonfiction essays that have moved me quite a bit. So often, you get people who write in a way where they want their readers to know that they’re smart, and they’re going to use really big words, and they’re going to use really big concepts. But Wendell writes in a way that is engaging and familiar, and I think that is one of many things that makes it really powerful.

Chapter 16: You raise cattle for slaughter. How do you reconcile that with your commitment to the well-being of farm animals?

Lamb: That’s something that Wendell Berry has written about. I think our goal in the production of meat is to do everything we can to minimize cruelty and ensure a good existence for that animal’s life. There are really responsible ways in which you can give a wonderful life to an animal and avoid a lot of the climate issues that we so often hear of when it comes to livestock production and raise something that’s good for the land and good for people. I don’t think in the current overarching system that we have for much of our meat production in the United States that we’re doing a great job of that.

I think a lot of smaller scale farmers who are raising beef and sourcing it locally are [doing that]. But I think the predominant approach in our agri-industrial system is things like massive feedlots where livestock have miserable lives. They may be initially born in Tennessee, shipped all the way to Oklahoma and pumped full of grain for several weeks or a couple of months, slaughtered, and then shipped right back to Tennessee to be sold in a Walmart. I think that is a horrible system, and as much as we can do to get away from that type of approach, even if it means reducing some of our beef consumption as a society, we need to be heading in that direction.

Chapter 16: The book has a lot of statistics about how small farms are vanishing because of development and large-scale farming by corporations. Why is it important how farming is done?

Lamb: There are a variety of reasons. As farms grow larger and industrialize and you need fewer people and fewer families, a lot of rural communities are deserted. A lot of rural communities are losing population throughout the United States. Their local economies, which once hinged on tight-knit and vibrant communities of small and mid-sized farmers to support farm businesses and bakeries and sandwich shops and hardware stores and mechanics, all of those secondary services dry up when those farms disappear. So there are economic reasons.

There are environmental reasons. … You can look at ecological destruction and the contributions of industrialized agriculture to climate change. You can look at agricultural reasons. As farms specialize and mono-crop more, as land is lost near major urban cores, you lose a lot of the capacity for local and regional food movements. If all the farms outside of Nashville exclusively grew corn and soybeans, a lot of the farmers’ markets in Nashville that can be so vibrant, they’re going to dry up. It’s the same thing for Memphis and Chattanooga and Knoxville and any other city in any other state.

One additional reason that doesn’t necessarily fit neatly into a box stands out to me. Farming is, or at least it can be, one of the most intimate connections that we have with the earth. That power of growing something from a seed and watching it develop and caring for it, of caring for animals, those sort of intimate connections with the earth, I argue those relationships that we build are important. As acreage is getting bigger and bigger, and there is less actual connection to the ground, we lose that intimacy and that relationship and that awareness. Small and midsize farmers — it’s not the only way, but it is certainly one of our society’s deepest ways of continuing a connection with the earth. In those good connections, I think can really come good stewardship. That is another reason why I think it’s so important that we support farmers of those small scales and try to get even more farmers out there who are willing and interested in farming at that scale.

Chapter 16: You compare running a good farm to being in a good marriage. Can you flesh that out for me?

Lamb: A marriage is a partnership, right? If it’s done well, both parties in the marriage will flourish. It takes a lot of work. … It takes effort, it takes sacrifice. But in the end, there’s a fulfillment there, a joy that I think is really powerful. I think the same goes for farming when farming is anchored in love and understanding. It is exceptionally rewarding.

Chapter 16: Is it going too far to relate these principles to having a successful life?

Lamb: Something like 1% of American society lives on a farm, so most people who read this book are not going to be farmers, and I don’t think we need a mass back to the land movement. Instead, we can work to practice these virtues where we already are. That might mean connecting with an urban park. It might mean volunteering in a community garden. It might mean growing a few tomato plants in your backyard.

If you’re living in an extremely dense area like New York City, it might mean cultivating a relationship with a street tree in the sidewalk and paying attention to that tree as you’re walking to work — trying to really be aware of how it changes throughout the season, perhaps giving a little bit of water out of your water bottle as you pass by as a gesture of love. I think that we can practice those virtues wherever we are, with the idea being if we all work together to love and care for specific places on Earth, the planet itself will be better off for it. If we take care of the parts, the whole will be healthier.

Chapter 16: Any last words?

Lamb: Good farming matters, and it matters for the sake of the land itself. It matters for farming people. But because we all eat and drink and breathe and live, it matters for all of us. The lessons farmers teach us through their lived example are really important. If we look at them, if we listen to them, if we heed their example, we can all be a lot better off whether we live in a rural community, a suburban subdivision, in the heart of a town, or the downtown of a major city. This book has a farm on the cover. It’s about farms and farmers, but it’s really for all of us.

Jim Patterson is a Nashville freelance writer whose work appears often on the United Methodist News website. He has been a reporter for The Associated Press in Nashville and senior writer and public affairs officer for Vanderbilt University.