A Different Dark

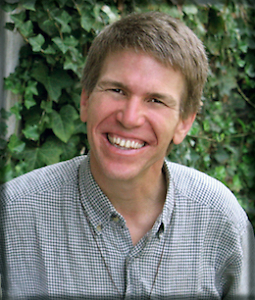

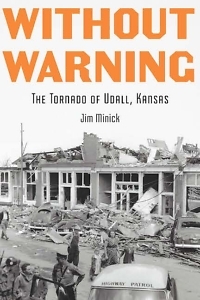

Jim Minick captures the human drama of a deadly F5 tornado in Without Warning

Jim Minick’s Without Warning: The Tornado of Udall, Kansas provides a gripping account of the deadliest tornado in Kansas history, which in 1955 killed 82 and injured 270 in a town of only 600 residents. This means that fewer than half the residents, many of whom become memorable characters in Minick’s account, survive the story unscathed, a fact that allows Minick to infuse his narrative with suspense and poignancy before, during, and after the storm.

The book opens with a 12-year-old paperboy delivering the afternoon edition to most homes in Udall. As he flings papers to the porches of specific families, readers can’t help but wonder how they — not to mention the paperboy — will fare. Ensuing scenes depict vignettes of small-town life as it happened that afternoon and evening. Interspersed with these are actual teletypes — printed in all caps — sent to area radio stations by the National Weather Service. Each is a little more ominous than the one preceding it.

Widely published as a poet and essayist, Minick’s previous books include a memoir, The Blueberry Years, and a novel, Fire Is Your Water, and poetic imagery infuses his scenes. The paperboy’s mother, for example, examines the still-distant storms at sunset:

Nina stepped out on the back porch to check the weather. On the western horizon, the sun cast an odd light that seemed to be pressed close to the earth, while the overburden of clouds rolled higher and higher into the sky. Those clouds moved as if they wanted to beat back the night and replace it with a different dark.

Meanwhile, across town, a popular schoolteacher, “a small woman with pale blue eyes,” greets a hundred guests at her bridal shower, held in a new community center. The 27-year-old is overwhelmed by the many gifts they bring, including “a waffle iron and tablecloths, cookbooks and a mixer, sheets and towels.” As rain and thunder begin outside, some guests leave — but many remain until the electricity goes out. Soon the building comes apart, room by room.

The rich characters and taut pacing in Without Warning recall two other notable works of weather nonfiction, both published in the 1990s: The Perfect Storm by Sebastian Junger and Issac’s Storm by Erik Larson. Like Junger, Minick spent hundreds of hours interviewing survivors and family members to flesh out the people at the center of the storm; like Larson, he pored over hundreds of pages of newspaper articles, weather service data, and official records to make his account as factual as possible.

The rich characters and taut pacing in Without Warning recall two other notable works of weather nonfiction, both published in the 1990s: The Perfect Storm by Sebastian Junger and Issac’s Storm by Erik Larson. Like Junger, Minick spent hundreds of hours interviewing survivors and family members to flesh out the people at the center of the storm; like Larson, he pored over hundreds of pages of newspaper articles, weather service data, and official records to make his account as factual as possible.

The combined effect of such human and meteorological detail is that by the time the tornado reaches the town at 10:35 p.m., the book has become impossible to put down. The remainder of the story takes survivors through that horrendous night and into the days, months, and years that follow. Chapter titles hint at the emotional stages shared by many who have endured such disasters: “Hit by Emptiness,” “Bigness of Heart,” “So Many Dead,” and “Trying to Find Normal.” What emerges from these chapters is human resilience and, ultimately, kindness.

A few days after the storm, Minick writes, “Three types of people started to stream into Udall — gawkers, helpers, and reporters, who sometimes gawked and sometimes helped.” Among the latter, one reporter asks the mayor’s daughter “what she missed most that the storm had taken.” The girl mentions her dog, Corky, and a new camera she had used to take “silly pictures” of him. The next day a National Guardsman spots the muddy pup alive in a field and carries him to town for a happy reunion. Such moments provide brightness amid the challenge of rebuilding the destroyed town and its families.

Minick asks in an epilogue, “What stories are we creating now to carry us forward through the great upheaval called the climate crisis?” He mentions the increasing number of weather disasters over the past half-century. After reflecting on similar weather events that have struck his home state of Virginia, Minick writes that “the Udall story becomes more and more relevant.”

Within parts of the Udall aftermath, Tennessee readers might hear echoes of the Cookeville tornado of 2020 or the East Tennessee storms this past September. Minick calls for “stronger, generous communities to help others when they struggle,” writing that “any path through the climate crisis will not be easy because the upheaval will be — and already is — great.” Without Warning thus becomes more than a fascinating and emotional read: It offers a guide for enduring disasters yet to come.

Michael Ray Taylor is the author of Hidden Nature and other books. He lives in Arkansas.