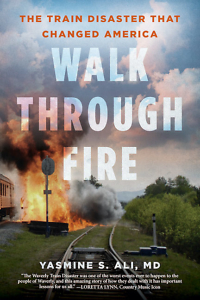

A Disaster and a Dauntless Town

Meet the heroes and martyrs of the Waverly Train Disaster in Walk Through Fire

It’s a tragedy with a title: The Waverly Train Disaster. In its wake, the United States remade its emergency response and zeroed in on rail safety, but the story of heroes, martyrs, and human triumph over catastrophe in the Middle Tennessee town of 4,000 had been left behind. In Walk Through Fire, Dr. Yasmine S. Ali sets the record straight.

Even readers familiar with the facts about the inferno 45 years ago will find a gripping drama in Ali’s recounting of the tense hours that led up to the explosion of a propane-filled tank car in her hometown and the harrowing hours after in a “two-room ER.”

Relying on the memories of survivors as well as scrupulous research, Ali describes the first response to a late-night pileup of 23 L&N Railroad cars on February 22, 1978, and the town’s gradual relaxing of its guard over two tank cars in the wreck as cleanup crews moved in. The horror began at 2:55 p.m. on February 24, when thousands of gallons of flammable gas exploded.

The accident killed 16 and maimed dozens of others while incinerating a section of the town. It was national news and set off intense investigations by the National Transportation Safety Board and the Federal Railroad Administration. On its heels, President Jimmy Carter created the Federal Emergency Management Agency by executive order.

In the author’s narrative voice, simultaneously empathetic and authoritative, the facts are the backdrop to a story about grace in a town described on its website as “a very neighborly community.” Ali, a cardiologist and medical writer, has a gift for translating her scientific knowledge into clear prose, complemented by her deep knowledge of the place where she grew up and affection for its people.

Ali is especially close to two of the heroes of the medical response to the explosion. Her parents, surgeon Dr. Subhi Ali and gastroenterologist Dr. Maysoon Ali, met at DC General Hospital in Washington, D.C., and found their way to Waverly by answering a classified ad in The New England Journal of Medicine. Luckily for the townspeople, the surgeon they recruited had done years of training in a metropolis, where he treated not just gunshot and stab wounds, but burn injuries. Walk Through Fire is dedicated to Subhi and Maysoon Ali.

Before her husband was called in and took charge, Dr. Maysoon, as she was known in town, witnessed the first arrival of the blast’s victims. “She could not tell who any of them were, such was the extent of their burns. There was smoke rising from their skin, with the epidermis visibly sloughing off.”

Before her husband was called in and took charge, Dr. Maysoon, as she was known in town, witnessed the first arrival of the blast’s victims. “She could not tell who any of them were, such was the extent of their burns. There was smoke rising from their skin, with the epidermis visibly sloughing off.”

The reader is prepared for this horror by a pocket description of a boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion, or BLEVE. Waverly Police Sgt. Elton “Toad” Smith had just been to a seminar where he learned about BLEVEs and how “just one gallon of liquid propane can vaporize, all at once, to more than 250 gallons of flammable gas.” The damaged tank car at the site of the derailment had him thinking about such details; roughly 15 minutes later he was engulfed in flame.

We meet Smith first in a prologue titled “Ball of Fire,” as he finds himself “waist deep in an all-consuming flame that formed a wall for as far as he could see.” His dauntless recovery is one of the tales of heroism Ali tracks, and she credits him with inspiring her project.

The book provides impressive quick histories of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, the Civil War-era use of the local rails, the state of rail travel in the 1970s, the state of America’s emergency response systems, and the founding of what was known then as the Nautilus Memorial Hospital in Waverly.

But the beating heart of Walk Through Fire is the people of the community. As her story gathers, from the night of the derailment to the explosion and its aftermath, Ali introduces key players who responded to the crisis: a police chief, a young officer named Buddy Frazier who is now the town’s mayor, volunteer firemen, a funeral director, nurses.

The story goes deep because its subjects clearly trusted Ali with their memories.

The late country music star Loretta Lynn lived on a ranch nearby and wrote a blurb for Walk Through Fire, saying the train disaster “was one of the worst events ever to happen to the people of Waverly.” A reader might think that calling the explosion just “one of the worst” was overly cautious, but in fact, Waverly endured a similarly devastating disaster in August 2021, when a flash flood destroyed 272 homes in the county and took 20 lives. In a coda to Walk Through Fire, Ali finds solace in the thought that, just as the train wreck changed disaster response and rail safety in the country, the Waverly flood may galvanize a response to climate change, drainage, and land use issues.

Formerly the books editor at The Commercial Appeal in Memphis, Peggy Burch writes for The Daily Memphian, where she was arts and culture editor. A member of the Humanities Tennessee Board of Directors, she holds a master’s degree in English literature from the University of Mississippi.