A Disturbing Sweetness

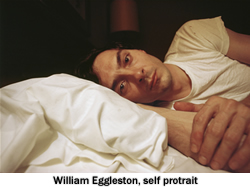

Poet Diann Blakely looks at the work of legendary Memphis photographer William Eggleston

One of the most striking images in Michael Almereyda’s documentary film, William Eggleston in the Real World, also appears on the cover of the new Eggleston collection, For Now: Eggleston’s wife, Rosa, lies sleeping with a yellow-flowered duvet bunched across her middle, one slender, aristocratic hand holding the sheets in place near the pubic region. Has the couple just had sex? Rosa’s lovely long legs end in feet that appear slightly dirty; the room is small, dingy, and low-ceilinged. The gaping closet door has a pink, pocketed storage hanging over the top, and a plastic, brown-nippled baby bottle sits on top of a staticky television. Remember when TV used to go “off the air” at night? There’s something yellow and disturbing about the portrait.

Disturbing, yes, but brilliantly riveting. Rosa appears often in these pages, and always as a captive of domesticity. The image of Rosa, bloated and exasperated, her mouth half-open and teeth bared like a vampire’s, calls to mind lines from Sylvia Plath: “Viciousness in the kitchen! / The potatoes hiss.” There’s another of her breast-feeding one of the Eggleston children and looking not at all happy about it, which brings to mind another poetic observation: as Randall Jarrell once noted of Eleanor Ross Taylor, “The world is a cage for women, and inside it the woman is her own cage.”

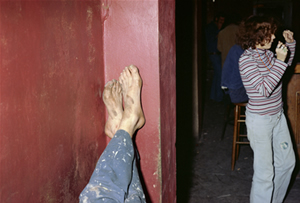

Yet there’s another, quite tender and lovely photograph of Rosa posing almost as though for a Christmas card: she turns her head toward Andra, the Egglestons’ middle child. You can almost hear Rosa whispering, “See Daddy? Turn your head and see Daddy?” Mother and daughter are in that saturated red for which Eggleston is famous. Yet “Bill Jr.” is dressed in black knee socks, black short pants, and a black, buttoned-up, velvet-looking frock coat. The color matches his mother’s and sister’s hair beautifully, but the innocence of his Peter Pan collar is spookily at odds with his facial expression. He stares balefully at the camera and appears as funereal as a crow.

Yet there’s another, quite tender and lovely photograph of Rosa posing almost as though for a Christmas card: she turns her head toward Andra, the Egglestons’ middle child. You can almost hear Rosa whispering, “See Daddy? Turn your head and see Daddy?” Mother and daughter are in that saturated red for which Eggleston is famous. Yet “Bill Jr.” is dressed in black knee socks, black short pants, and a black, buttoned-up, velvet-looking frock coat. The color matches his mother’s and sister’s hair beautifully, but the innocence of his Peter Pan collar is spookily at odds with his facial expression. He stares balefully at the camera and appears as funereal as a crow.

On the facing page crouches a large, puppy-eyed dog—a German shepherd mix?—whose own coat goes from tan to brown and then literally fades to black. There’s an important accompanying note: the “dog can be seen, improperly flipped, in Horses and Dogs: Photographs by William Eggleston (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994); the image has been recovered here and set right; otherwise none of the photographs on view have appeared in a previous book.”

I deeply suspect the ebony darkness of part of the image serves as preparation, given what I have heard about the famous Egglestonian wit, for the next plate: another mother-and child tableau, in this case the “mother” is a sweet-but-cautious-faced African-American nursemaid dressed raggedly and holding a newborn who stares transfixedly into the camera, one tiny fist thrust in its direction. It’s impossible to tell if the white cord we see is dangling from the child’s onesie or yet another thread from the coming-apart dress of “the help.”

I deeply suspect the ebony darkness of part of the image serves as preparation, given what I have heard about the famous Egglestonian wit, for the next plate: another mother-and child tableau, in this case the “mother” is a sweet-but-cautious-faced African-American nursemaid dressed raggedly and holding a newborn who stares transfixedly into the camera, one tiny fist thrust in its direction. It’s impossible to tell if the white cord we see is dangling from the child’s onesie or yet another thread from the coming-apart dress of “the help.”

“Sweetness,” like “wit,” is a word I’ve also heard to describe both Eggleston and his work, and both are in evidence several pages later in what I take to be a stunning tribute to his wife, one that is far less wistful and elegiac than the image that ends the book: a sterling silver vase atop an appropriately polished tray holding more than two dozen brilliantly red roses.

“Disturbing.” “Sweetness.” “Wit.” “Menace” is the word I’ve always used to describe the Eggleston photographs that I value most. Thus I was delighted to find that I was chiming in with Greil Marcus, whose essay “Two Women and One Man” is included in the collection. You don’t have to know a thing about Ike Turner to find him terrifying—and wearing, yes, a red sweatshirt—in For Now. (A note to future archivists: what a wonderful monograph could, and should, be made of Eggleston’s portraits of African Americans, frontal, in profile, or anonymously taken from behind.)

“Disturbing.” “Sweetness.” “Wit.” “Menace” is the word I’ve always used to describe the Eggleston photographs that I value most. Thus I was delighted to find that I was chiming in with Greil Marcus, whose essay “Two Women and One Man” is included in the collection. You don’t have to know a thing about Ike Turner to find him terrifying—and wearing, yes, a red sweatshirt—in For Now. (A note to future archivists: what a wonderful monograph could, and should, be made of Eggleston’s portraits of African Americans, frontal, in profile, or anonymously taken from behind.)

I once heard Eggleston compared to William Carlos Williams, and I thought the comparison was absurd. There’s nothing, at least, of the gentle domesticity in “The Red Wheelbarrow.” Perhaps Eggleston can be justly compared to the side of Williams revealed by “The Young Housewife”; here he sees his subject as a fallen leaf and then runs her over in his car. Is this what we’re viewing in For Now’s first photograph, a portrait of Leigh Haizlip? Wearing striped pajamas in Almereyda’s documentary, cute as those puppy-eyes I mentioned before, her own have become puffy, squinted, and death itself stares from behind them, wearing the world’s hurt, all of it, and none too well.

Click here to read Stanley Booth’s essay about his friendship with William Eggleston.

An exhibit of photographs by William Eggleston, “Unanointing the Overlooked,” will open at the Frist Museum of Art in Nashville on January 21. For details, click here.