A Dog's Best Friend

Robert J. Blake’s new picture book teaches kids how friendship really works

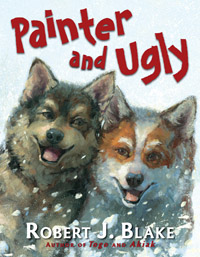

Robert J. Blake’s latest picture book features the tale of two best friends who’ll do anything to stay together. The protagonists of Painter and Ugly are a pair of dogs whose love for one another is nearly matched by their love of competing in Alaskan dog-sled races. Blake, who is also the book’s illustrator, shows the dogs spending every possible moment together. (Their names derive from an incident in which Painter spills a can of paint all over Ugly.)

In Painter and Ugly, Blake immerses readers in the story of a Junior Iditarod race, a grueling test in which a group of competing teenagers push their dog-sled teams on a nearly eighty-mile trek into the Alaskan wilderness, only to complete the return run the very next day, after a night of camping in the cold with their dog teams. While the impressive detailing of Blake’s text and illustrations brings the event to life, even more impressive are the techniques he uses to tell his story from the point of view of his canine heroes. Blake manages to convey the dogs’ affectionate bond, as well as the anxious panic of their separation and the elation of their eventual reunion.

Painter and Ugly is a picture book for kids that never underestimates its intended audience. Blake’s illustrations are energetically painted canvases, and his writing style features bursts of inspired language. And the most alluring aspect of Blake’s book is that he clearly cares for his characters as much as they care for each other.

Blake recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: When did you begin writing?

Chapter 16: When did you begin writing?

Robert J. Blake: I began writing in second grade when my terrific teacher, Miss Motichka, gave me one of those “Marble Pad” notebooks and told me to draw in there instead of on my tests. She said that if I kept all my ideas in one place I would never lose them, and that if I drew and wrote something every day, I could become a writer or artist when I grew up.

Because of her, I have created 127 sketchbooks to date. Professionally, I broke in as an illustrator first, a writer later. After illustrating phonics sheets and textbooks, editorial art for newspapers, filmstrips, magazines, and fine art, I illustrated my first book jacket for a Young Adult book called Crazy Eights by Barbara Dana (Harper & Row, 1978). The first picture book I illustrated was The Spider’s Dance written by Joanne Ryder (Harper & Row, 1981). After years of illustrating work for other authors, the first picture book I wrote and illustrated in my style was The Perfect Spot (Philomel Books, 1992).

Chapter 16: There are nice moments of language in the book. The man who separates Painter from Ugly has “a voice like a chainsaw,” and when Painter is searching for Ugly, you have his “nose tasting the air.” Where do inspired phrases come from?

Blake: Thank you. This is a very high compliment. I suffer each line in a story. If I have written any inspired phrases, they come from rewriting. I think of rewriting as trying to find one word that will do the work of ten and express something in your own personal way. In my book, The Perfect Spot, there is a scene in which a little boy tries to catch a frog and falls into the water. Writing out the action first, without worrying about grammar, spelling, or punctuation allowed me to get into the scene. Once there, I tried to connect with the situation of my character. I wanted to develop the rhythm of the event. The intent was to find a cadence in the words that would give a feeling of slipping on rocks and falling in the water, using little or no descriptive language:

The frog jumped.

I tried to grab it

but I missed.

Islippedandfelland

wound up in the stream.

The goal is to have the pictures and the text reinforce one another, fully immersing the reader in the book’s setting.

Chapter 16: Do you consider yourself an artist first and a writer second, or the opposite?

Blake: I feel that writing and art are the same thing, just different mediums. Being able to use art as a descriptive language helps me to limit my use of adjectives and adverbs, and that helps simplify the text.

Chapter 16: Your textures and brushstrokes really come through on the page. How do you create your images?

Blake: When I begin a book, I draw out a series of rectangles, with each one representing a different spread in the book. I draw a simple design in each one to show the flow of the book. An individual page requires anywhere from ten to one hundred line sketches. They are compiled into a prototype book called a “dummy” to show the editors the flow of the story and the balance of the words and art. The story and the artwork are continually refined to ensure full alignment. Finally, I turn to the canvas and rough out the image with graphite or charcoal. From there, I begin with an underpainting. Next, I block-in the entire piece, working all areas of the image up at once, staying as loose and fluid as I can. The detail only goes in at the very end.

Chapter 16: I was intrigued at how you painted most of the dogs in black-and-white tones, but you made Painter stand out in brown and blond and kept Ugly visible as a redhead with white patches. What other devices do you use to focus a reader’s eye in your illustrations?

Blake: Usually I design my pages to have the movement run from left to right, so that the reader’s eye moves through the book. I also try to move the eye around, sometimes being close to the scene, far away, above, below, inside it or out. Texture is important, too, especially when trying to show space.

Blake: Usually I design my pages to have the movement run from left to right, so that the reader’s eye moves through the book. I also try to move the eye around, sometimes being close to the scene, far away, above, below, inside it or out. Texture is important, too, especially when trying to show space.

Chapter 16: The paintings are very evocative. When Painter and Ugly are first separated, both of the dogs’ eyes are full of panic, and a reader can sense the tension on their leashes as they struggle to remain together. What is the difference between painting a portrait or a landscape and painting a scene that has to drive the emotions of a story forward?

Blake: An artist tries to create emotion through line, color, shape, and design. My goal is to go beyond what a camera can represent. My goal is to create a feeling. The way an artist does this becomes their own creative handwriting.

Chapter 16: Many animal stories focus on a main character with a sidekick. Painter and Ugly, despite their competitive natures, are equals and mutual supporters until the end. The whole drive of the narrative is their bond.

Blake: I have been lucky enough to have not one but four great best friends through my life, all of whom I am still close to (I dedicated the book to all of them). In each of the relationships, there are no alphas. Really, true friendship must be a relationship of equals.

Chapter 16: There is a palpable sense of excitement when the dogs are reunited. The moment is captured in a two-page spread that features a close-up of the two dogs running neck and neck, straight at the reader, without any text. It’s surprisingly dramatic and effective. How much influence do you have, as the writer and the artist, over the book’s design?

Blake: I am fortunate to be able to control the design from both a writer’s and illustrator’s perspective. I decide the format (vertical or horizontal), amount of pages, type breaks, placement of the title and half-title pages, and what image will appear. That being said, I trust the opinions of my editor and designer, and will look carefully at any suggestions they may have. We all want to create the best book possible.

Chapter 16: One of the best devices in the book is the way you convey how dogs hear WHATPEOPLEARESAYING. What’s the story behind that strategy?

Blake: The all-caps text is how words might sound to dogs—a kind of gibberish with a familiar word now and then, like SDFSETDDFS-GO OUT-DGLAHBLAAYUM.

Chapter 16: In reading about your writing process, I discovered that this book and your other stories usually begin with the question “What if?”

Blake: I try not to write about animals in an anthropomorphic way. The animals in my stories have fictional adventures, but they are based on real animals. For example, the book Little Devils is about three Tasmanian Devil pups. I traveled to Tasmania to talk to experts and observe Tasmanian Devils in their native, natural habitat. After a lot of observation, I asked the “What if?” question. What would the animal most likely do in a given situation of conflict?

Chapter 16: You are known for your in-depth research, and for this book you stayed with an Alaskan family with two children preparing for the Junior Iditarod. How did this book emerge from that experience?

Blake: To prepare for this story about two dogs and the Junior Iditarod Race, the Iditarod Trail Committee put me in touch with the Jeff Holt family. Mr. Holt was to race in the regular Iditarod that year. His son Jeff Jr. and daughter Taylar (that is the correct spelling) were to race in the Junior Iditarod. The Holts graciously took me in at their home in North Pole, Alaska. Being an on-site observer gave me the opportunity to see the real and subtle challenges faced by the family and the dogs. I spent every day actively involved with the teams, then working in my sketchbook, writing down the words and drawing the images I felt would make my story. All the while, I became closer to a certain dog on Jeff’s team named Painter. He always seemed to be sniffing the air, listening, and watching. I asked Mr. Holt what Painter might be looking for and he told me that Painter had only recently joined his team. He’d been owned by another musher and had a best dog-friend on that team named Ugly. “Maybe he misses his friend,” Mr. Holt said. And then the idea came to me—WHAT IF Painter missed his best friend? WHAT IF he sensed that his friend was in the race? WHAT IF they communicated a way to get together? And WHAT IF I told it from a dog’s point of view?

Chapter 16: Even though this is a book for children, I feel like it’s given me a working knowledge of dog-sled racing generally and the Junior Iditarod race in particular. Why is this level of authenticity so important to you?

Blake: There are two reasons. First, for the experiences the events and place provide. It has been very interesting making each and every one of the books. I have met some amazing people all around the world. What could be better than to be rich in experiences? The second reason goes back to my days at the Paier School of Art. My book-illustration instructor, the renowned Leonard Everett Fisher, told me many times, “Blake, these are not comic books. They are literature. We are privileged to be allowed to make them, and as such it is our calling to create books that have an inherent integrity.” I agree and hope I have been able to achieve that goal.