A Feeling Not Unlike Happiness

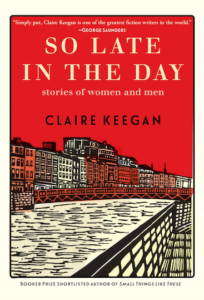

Claire Keegan’s stories chart the good and bad of romantic relationships

Claire Keegan’s new story collection, So Late in the Day, has a misleading subtitle. “Stories of women and men” sounds charming, potentially romantic; in reality, these tales make a convincing case for singlehood, especially for women. The stories’ premises evoke classic Hollywood — the end of an affair, a chance encounter, a passionate weekend — but Keegan twists expectations in ways that not even Cary Grant could unravel.

The source of Keegan’s popularity, soaring in recent years with the success of her novels Small Things Like These and Foster, is less her narrative ingenuity than the quality of her prose. Though her stories are rife with details from her native Ireland, where she’s revered among literature’s first rank, her characters have a universal appeal that has raised her profile in America, too. Critics praise her ludic imagery and her knack for capturing complex emotions with few brushstrokes. Her fiction rewards rereading, when her sentences can be savored for their precision — not the surgical incisiveness of Thomas Mann, but the compassionate minimalism of Anton Chekhov (whom Keegan references by name here).

Keegan masterfully deploys telling details, efficient metonymy that projects inner states onto objects. In the title story of this collection, she associates the early, loving weeks of a relationship with the nourishing items a couple buys at the farmers’ market: “loaves of sourdough bread, organic fruit and vegetables, plaice and sole and mussels off this fish van, which came up from Kilmore Quay.” Contrast that abundance with the state of the man’s refrigerator when he reverts to bachelorhood. “There was nothing fresh there: a jar of three-fruits marmalade, Dijon mustard, ketchup and mayonnaise,” Keegan writes. “He took a Weight Watchers chicken & veg out of the freezer and stabbed the plastic a few times with a steak knife before putting it in the microwave for nine minutes.”

The central character in that story is Cathal, whose semi-dreary life is briefly enlivened by Sabine, a lively woman who is sufficiently self-conscious about her physical flaws to consider settling for him. No sooner does she move into his place, however, than Cathal begins to bristle at her intrusion. When he lets petty selfishness torpedo their chance at happiness, Sabine concludes that her cynical friend Cynthia may be right about men, “that a good half of men your age just want us to shut up and give you what you want, that you’re spoiled and become contemptible when things don’t go your way.”

The central character in that story is Cathal, whose semi-dreary life is briefly enlivened by Sabine, a lively woman who is sufficiently self-conscious about her physical flaws to consider settling for him. No sooner does she move into his place, however, than Cathal begins to bristle at her intrusion. When he lets petty selfishness torpedo their chance at happiness, Sabine concludes that her cynical friend Cynthia may be right about men, “that a good half of men your age just want us to shut up and give you what you want, that you’re spoiled and become contemptible when things don’t go your way.”

Cathal at least harms only himself, whereas the other two stories in this collection include men whose toxicity is more dangerous. In “The Long and Painful Death,” an Irish writer is just settling into her residency at the Heinrich Böll Cottage (a real place on the island of Achill) when a retired German professor imposes on her for a tour of the house. Their interactions, which begin cordially but take a nasty turn, affirm her decisions to reject the men in her past who proposed to her. “She felt great fortune, now, in not having married any of these men,” she thinks, “and a little wonder at ever having said she would.”

The final piece, “Antarctica,” was also the title story of Keegan’s first collection, published in 1997. Here it offers readers the opportunity to gauge how her writing has evolved over two decades. “Antarctica” begins with a “happily married woman” on a solo shopping trip to London who blithely wonders “how it would feel to sleep with another man … before she got too old,” though she “was sure she would be disappointed.” The story maintains a light tone until its end, when it takes a dark turn. That pattern, comedy turning tragic, is the reverse of what happens in Small Things Like These and Foster, where Keegan pushes young characters to the brink of chasms before steering them to safety.

While her vision has grown rosier, Keegan retains her penchant for creating lovable eccentrics. The protagonist of “Antarctica” feels peculiarly drawn to documentaries about the icy continent. “I always thought hell would be an unbearably cold place where you stayed frozen but you never quite lost consciousness,” the married woman tells her lover. “There’d be nothing, only a cold sun and the devil there, watching you.” Even Cathal, mired in loneliness after the implosion of his engagement, finds joy in drinking from his tap: “A feeling not unlike happiness momentarily crossed over his lips then, and down his throat.”

Another notable trend in Keegan’s work is the diminutive size of her last three books, each of them stretched with ample margins to reach 100 pages. These are wee books, perfect for stocking stuffers, but they offer a generous vision. Each requires little more than an hour to read, but Keegan’s quirky people will stick with you long afterward.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.