A Finely Drawn Character

Robert Gipe’s illustrated debut novel, Trampoline, introduces a troubled teen coming of age during an Appalachian coal war

In 1980, eleven years after the author’s suicide, John Kennedy Toole’s classic, A Confederacy of Dunces, was published by the Louisiana State University Press. The following year it won the Pulitzer Prize in fiction. That may have been the last time a university press introduced a major American voice—the last time, that is, until now: Ohio University Press has just published Trampoline: An Illustrated Novel by Kingsport native Robert Gipe. Trampoline is a classic American coming-of-age-novel in the tradition of To Kill a Mockingbird, Catcher in the Rye, and True Grit. More than that, it represents a new kind of novel, a form of storytelling that blends superbly crafted Southern prose with the visual intimacy of a graphic novel, including 220 comics-style drawings that keep the book grounded in the world of an Appalachian teenager.

Trampoline tells the first-person story of Dawn Jewell, a fifteen-year-old living with her brother and her grandmother in fictional Canard County, Kentucky. Their home sits on the flanks of Blue Bear Mountain, which is now slated for strip mining. “I was a freak, soft and four-eyed,” Jewell describes herself, “with black fingernail polish, a dead daddy, a drunk momma, a crackhead brother, outlaw uncles, and divorced grandparents who made trouble for normal people every time they come off the ridge.”

Trampoline tells the first-person story of Dawn Jewell, a fifteen-year-old living with her brother and her grandmother in fictional Canard County, Kentucky. Their home sits on the flanks of Blue Bear Mountain, which is now slated for strip mining. “I was a freak, soft and four-eyed,” Jewell describes herself, “with black fingernail polish, a dead daddy, a drunk momma, a crackhead brother, outlaw uncles, and divorced grandparents who made trouble for normal people every time they come off the ridge.”

The trouble Jewell’s grandmother makes is classic grass-roots activism: a petition to the governor to stop the mining operation at Black Bear. When Jewell gives a brief interview on community radio, she becomes a reluctant environmental spokesperson and target for her neighbors, whose livelihood depends on the mine.

But coal battles are the least of Jewell’s worries. Since her father’s death, her mother has been addicted to alcohol and drugs and spends most of her time with the least law-abiding of Jewell’s “outlaw” uncles. Jewell and her brother fight constantly—pointed verbal exchanges that blossom into brutal physical altercations. At school, her only friend encourages her to drink vodka and cut class. Jewell imagines a romance with a DJ on the local station that continually plays her radio interview, but the only real intimacy in her life comes from occasional conversations with her grandmother or her grandmother’s ex-husband, who lives alone in an old cabin that Jewell often visits. Here’s her description of his place:

The air smelled of coal smoke from my papaw Houston’s house back up on the hillside. I could see him in my mind, surrounded by his music, fire going in the stove, not like pioneer days, not that old feeling, but like something you couldn’t find no more in the world today.

Everything was blue and gray out. It was so quiet I could almost hear Houston’s fire crackling and popping. My cheeks were numb.

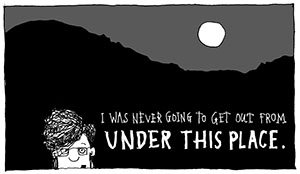

I was never going to get out from under this place.

That last line is delivered, like so many of Jewell’s pronouncements, not in standard prose, but in a cartoon panel stuck at the bottom of the page, this one depicting Jewell, the dark mountain, and a full moon. In the book’s illustrated panels, Jewell looks directly at the reader, her hair an unruly mess, large hand-lettered words ringing on the page. Her features appear thick and masculine—for months, one kid at school honestly thinks she is a boy. In many of these panels Jewell wears a t-shirt emblazoned with ironic text, but her wardrobe and its message change constantly with her mood.

In Trampoline the drawings are more than “illustrations,” despite the book’s subtitle. While the book could have been a fine first novel without art, Gipe allows key plot elements to flit out of prose into comics form and then back into prose again. “The fragmented narrative of the panel-by-panel format engages the reader in a particularly active role of interpretation and inference,” Josh Neufeld, author of AD: New Orleans After the Deluge and other graphic nonfiction, has written. “Comics speak in an intimate voice.”

In Trampoline the drawings are more than “illustrations,” despite the book’s subtitle. While the book could have been a fine first novel without art, Gipe allows key plot elements to flit out of prose into comics form and then back into prose again. “The fragmented narrative of the panel-by-panel format engages the reader in a particularly active role of interpretation and inference,” Josh Neufeld, author of AD: New Orleans After the Deluge and other graphic nonfiction, has written. “Comics speak in an intimate voice.”

The overall effect of the art in Trampoline forces the reader more deeply into Jewell’s point of a view as a smart fifteen-year-old surrounded by the poverty and desperation of Appalachia. Various plot elements—her mother’s plight, the fate of the mountain, the physical dangers posed and endured by her outlaw uncles, and her desire to turn romance with the DJ from fantasy to reality—gradually converge in a stunning climax. Yet the somewhat standard story structure is subtly amplified by the role of the drawings, with the visible narrator literally looking the reader in the eye. Late into a difficult night in which she has run away into snow-covered woods, for example, Jewell becomes lost and frightened. A long descriptive paragraph ends with this revelation:

There was a light in the woods, but I couldn’t tell where it came from. It seemed it came from the mountain. The total amount of water in the mountain began to freak me out. I did. I freaked out about the water. Stupid. I sat down on a fresh-fallen log. The wind crackled through the leaves clinging to the limbs. Sounded like a clutch of old women whispering at the back of a cold, empty church. The light was dwindly and low, and I wished you were there.

Who?

And then she answers in an illustration, her face deadpan as ever: “You, stranger.”

As with most teens who have shared too much, she quickly backs off: “Ha ha. I want you to know what it’s like.” And then the story progresses through another few paragraphs of prose.

Trampoline is a truly new sort of novel, one in which the masterful prose and intimate drawings work together to tell a powerful story. In Gipe’s hands, Jewell’s voice is musical and honest, her language and syntax brooking no nonsense and yet capturing the beauty and nuance of mountain life that others around her miss.

Trampoline is a new American masterpiece.

Michael Ray Taylor teaches journalism at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is the author of several books of nonfiction and coauthor of a forthcoming textbook, Creating Comics as Journalism, Memoir and Nonfiction.