A Game of Pure Chance

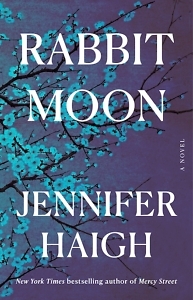

Jennifer Haigh’s Rabbit Moon combines intellectual heft with the readerly pleasures of a thriller

The opening pages of Jennifer Haigh’s Rabbit Moon raise questions about the nature of the universe. The epigraph from Voltaire suggests that the world is deterministic: “Chance is a word devoid of sense; nothing can exist without a cause.” Yet, in the first scene, a random car accident in Shanghai leaves a young American woman in a coma, barely clinging to life. Is our existence “a game of pure chance,” as Haigh describes the Fan Tan table in Macau, or does it follow predictable rules and patterns?

Such questions preoccupy the parents of the accident victim, Linsey Litvak, after they fly to her bedside. Claire and Aaron, who divorced three years earlier, thought Lindsey was teaching in Beijing, 750 miles away. Shanghai police direct them to Lindsey’s apartment, which is nicely furnished, with closets full of elegant dresses. Already frustrated with their daughter for dropping out of Wesleyan, Claire and Aaron struggle to make sense of Lindsey’s journey. They agree on two basic conclusions: Her downfall, from promising college student to coma patient in Shanghai relates back to her high school affair with an older man, and this crisis is clearly the other parent’s fault. (See, causality isn’t complicated after all.)

Told alternately through Claire’s and Aaron’s eyes, the novel’s early section is dotted with plot questions typical of a classic mystery. Why was Lindsey in Lujiazui, Shanghai’s financial district, at 4 a.m.? What is her relationship with Johnny Du, a hairdresser who keeps his flamboyant lifestyle secret from his traditional parents? Why has Lindsey kept her move a secret from Grace, her younger sister, whose adoption from China was Lindsey’s motivation to learn Mandarin in the first place? As they learn more about her life, it becomes clear that they don’t know their daughter at all.

After the novel’s long first part, the narrative jumps back a year and switches to Lindsey’s point of view. Immediately, Haigh returns to the question of chance versus determinism: If Lindsey and then-boyfriend Zach, visiting Shanghai for a weekend, had wandered into a different bar, she would not have encountered the intriguing stranger who alters her life’s course. With these “statistically improbable” meetings driving her fate, the novel seems to suggest that Lindsey suffers cataclysmically bad luck. On the other hand, maybe cosmic forces are at play: The novel’s central action takes place in 2016, the Year of the Monkey, when, according to Johnny Du, “gross misfortune was almost inevitable.”

For better or worse, Lindsey is destined to stand out. Six feet tall, red-haired, and “fatally, ruinously beautiful, the kind of beauty that makes a girl a target,” she would be distinctive anywhere; in China, she’s “conspicuous as a flamingo.” She’s as brilliant mentally as she is physically. Gifted at languages and the sciences, she could have had her pick of careers. Loyal to friends and doting on Grace, Lindsey deserves the gods’ beneficence; instead, she becomes the object of their sadistic tortures.

For better or worse, Lindsey is destined to stand out. Six feet tall, red-haired, and “fatally, ruinously beautiful, the kind of beauty that makes a girl a target,” she would be distinctive anywhere; in China, she’s “conspicuous as a flamingo.” She’s as brilliant mentally as she is physically. Gifted at languages and the sciences, she could have had her pick of careers. Loyal to friends and doting on Grace, Lindsey deserves the gods’ beneficence; instead, she becomes the object of their sadistic tortures.

The causal chain leading to Lindsey’s accident begins not in China but, as her parents perceive, several years earlier when she falls in love with the handsome father of a family she babysits for. “Dean Farrell had been the end of her childhood, though at the time she hadn’t thought so. The very suggestion would have offended her,” Haigh writes. When their relationship is exposed, the fallout for the Litvak family is profound and lasting. Lindsey blames her mother for keeping her from Dean. Claire blames Aaron for handling the matter quietly (Claire wants blood). Afterward, Aaron views his wife as congenitally unhappy — “prickly” is the term he uses — and the divorce follows apace. As for Lindsey, she tries to move on emotionally but remains fixated on her first love, an older-man obsession that in Shanghai leads to more heartbreak.

Haigh’s achievement in Rabbit Moon is to combine the intellectual heft of a philosophical novel with the readerly pleasures of a thriller. The pace feels urgent but never rushed. She supplies a steady stream of plot information to keep the pages turning, yet pauses periodically to reflect on tangential topics. Motifs reappear to underscore prominent themes. The titular “rabbit moon,” when a full moon appears to be wearing “bunny ears,” echoes the Mickey Mouse ears that inundate Shanghai in anticipation of the opening of the city’s Disney Resort.

The novel’s construction is clean, but the resolutions are messy — appropriately so, given the chaotic nature of marriage, parenthood, and young love. As she has demonstrated in novels such as Heat & Light (2016) and Mercy Street (2022), Haigh has an acute appreciation of moral ambiguity, especially regarding wounded characters who struggle to find a way forward. Honest about self-destruction but optimistic about redemption, Haigh’s novel ponders the big questions but doesn’t settle for the faux comfort of easy answers.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.