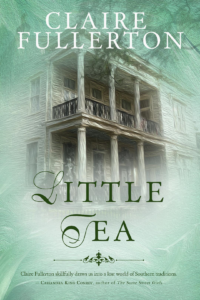

A Girl Complete

Claire Fullerton’s Little Tea explores the power of women’s friendships

“To a Southerner, any place outside of the South is ‘out there.’ There’s the South, and then there’s everywhere else,” says Celia Wakefield, the narrator and protagonist of Claire Fullerton’s fourth novel, Little Tea. Forty-five-year-old Celia has worked hard to put the tragic events of her own Southern upbringing behind her. Happily married and living in California, she rarely returns home, but when her friend Renny calls to say that another friend, Ava, is in trouble, Celia must go.

The three women have known each other for more than 30 years. Celia thinks she is prepared for the journey until she lands on the tarmac in Memphis to a familiar sensation. “There, the past comes hurtling full throttle to meet me,” she admits. “If it’s not at the gate, it’s waiting in the parking lot, smiling sardonically and holding the form-fitting coat of my childhood.”

The three women have known each other for more than 30 years. Celia thinks she is prepared for the journey until she lands on the tarmac in Memphis to a familiar sensation. “There, the past comes hurtling full throttle to meet me,” she admits. “If it’s not at the gate, it’s waiting in the parking lot, smiling sardonically and holding the form-fitting coat of my childhood.”

As the three friends wind down and catch up at Renny’s lake house, memories come flooding back of their youthful mistakes and roads not taken. Renny is a successful veterinarian, divorced and independent, determined never to marry again. Careless Ava is unhappily married, drinking too much, and contemplating potentially catastrophic life changes. Practical Renny loses patience with Ava’s dubious decisions. Celia, the peacemaker, tries to remain neutral and upbeat, but the effect of being once more with her longtime friends is palpable and mysterious. “I know now, since I’m well into my adulthood,” she says, “that there’s a side to the unions made in high school that has perpetual resonance, a side that remains in arrested development that will never let you forget who you essentially are.”

Fullerton alternates the present action at the lake with Celia’s recollections of her formative years on her family’s cotton plantation in Como, Mississippi, 45 miles south of Memphis, in the 1980s. Young Celia’s best friend is an African American girl named Little Tea, whose parents live and work on the property. The two children discover the world together in the forests and fields surrounding the farm. They spend their time fishing in the pond, following animal trails through the woods, and searching for buckeyes to add to their collection. It’s a near idyllic childhood. But when Celia turns 10, her parents move her and her two older brothers to Memphis. “My reaction to the move was complete despair,” Celia recalls, “for the thing about being a Southern girl is they let you run loose until the time comes to shape you.”

Fullerton alternates the present action at the lake with Celia’s recollections of her formative years on her family’s cotton plantation in Como, Mississippi, 45 miles south of Memphis, in the 1980s. Young Celia’s best friend is an African American girl named Little Tea, whose parents live and work on the property. The two children discover the world together in the forests and fields surrounding the farm. They spend their time fishing in the pond, following animal trails through the woods, and searching for buckeyes to add to their collection. It’s a near idyllic childhood. But when Celia turns 10, her parents move her and her two older brothers to Memphis. “My reaction to the move was complete despair,” Celia recalls, “for the thing about being a Southern girl is they let you run loose until the time comes to shape you.”

Over the years, Celia adapts to the social constraints of city life as her circle of friends and opportunities expand. Little Tea has a different experience and dreams of escaping the suffocating racism of Mississippi through an athletic scholarship to a college further north. Still, despite the cultural differences that threaten their bond, they remain close until a shocking act upends both their families and their lives.

Fullerton brings to vivid life the patterns of Southern speech and culture she portrays. She is especially adept at illuminating the power of friendship to soothe, to support, to protect — and sometimes, to tell hard truths and expose the wounds that have not healed. Celia marvels at how well she, Renny, and Ava understand one another and resume their former relationships, even after so many years apart. “Combined, we were a girl complete,” Celia admits. “Separately, we were inchoate and in need of each other, like solitary pieces of a clock that were useless until assembled, but once assembled, kept perfect time.”

Tina Chambers has worked as a technical editor at an engineering firm and as an editorial assistant at Peachtree Publishers, where she worked on books by Erskine Caldwell, Will Campbell, and Ferrol Sams, to name a few. She lives in Chattanooga.