A Great and Challenging Game

Memphis author and bookseller Corey Mesler talks about art and commerce

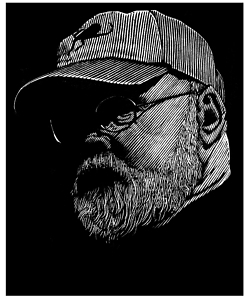

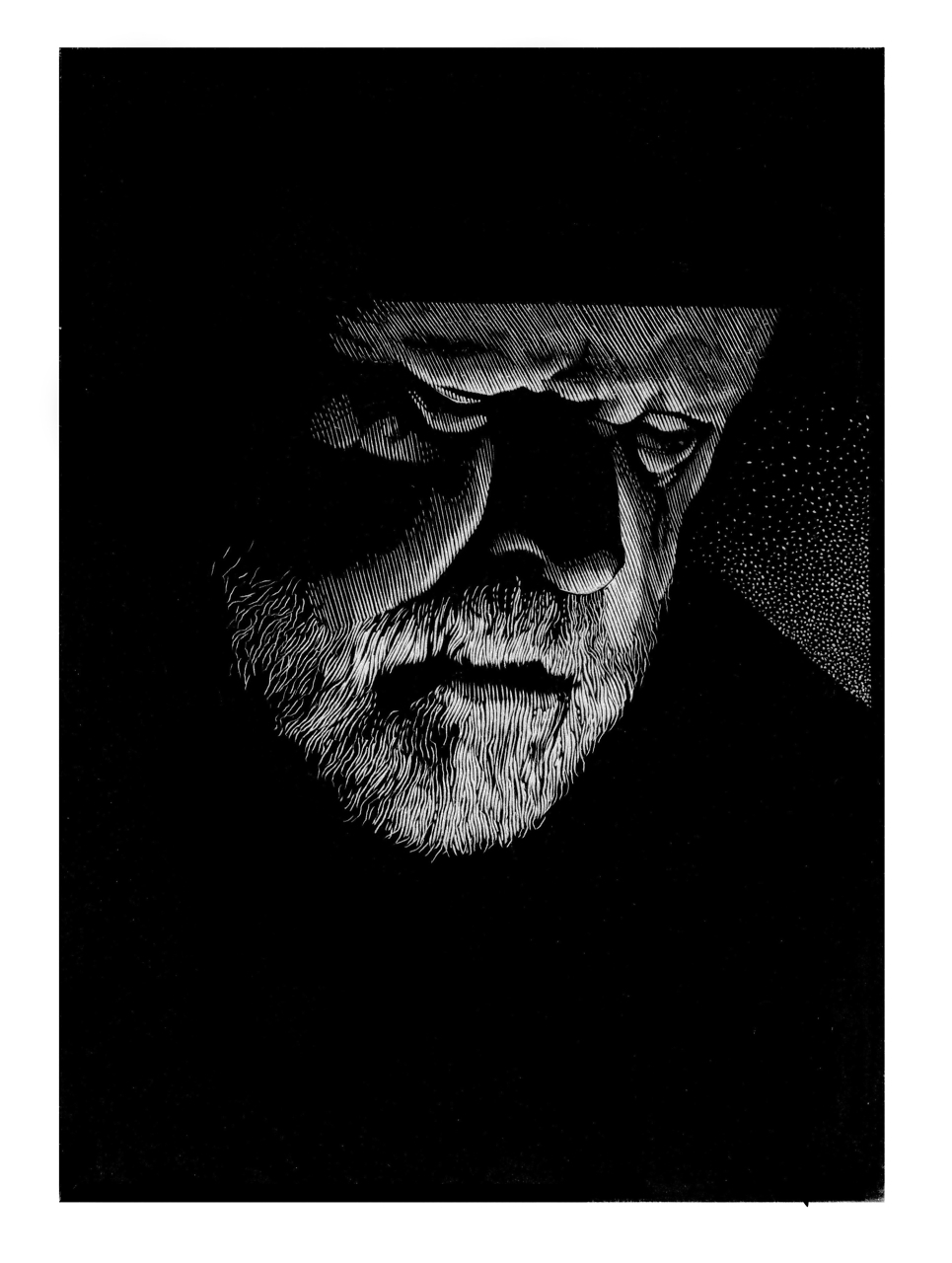

“Graceful,” “piercingly funny,” “unique,” and “wise” are a few of the adjectives that have been used to describe the work of Corey Mesler, whose novels and stories have been lauded by the likes of Megan Abbot, John Grisham, and Robert Olen Butler. His poetry has been widely published and has twice appeared on Garrison Keillor’s The Writer’s Almanac. Fellow Memphian Steve Stern, the author of last year’s critically acclaimed novel The Frozen Rabbi, calls Mesler “an original” and “the real thing.” Even with such recognition and eight published books to his credit, Mesler remains little known outside a small circle of fans, but that state of affairs seems likely to change as this prolific and inventive writer continues to send his words out into the world. He has two new books out this year: a poetry collection, Before the Great Troubling, and a volume of short fiction, Notes Toward the Story & Other Stories.

Mesler is a writer who likes to mix it up, indulging in wordplay, toying with form and voice, and lassoing high- and low-culture references into his narratives. His 2002 novel, Talk, is written entirely in dialogue. The Ballad of the Two Tom Mores, a bawdy tale set in small-town Arkansas, includes among its cast of characters a set of triplets named Venny, Viddy, and Vichy. The nineteen pieces of short fiction in the just-released Notes Toward the Story & Other Stories display Mesler’s characteristic playfulness. The title story is a sorry domestic tale conveyed via seemingly random writer’s notes. “Delitescent Selves” takes the form of a book review, and “Monster” features an outcast creature named Genet. Mesler makes these writerly antics work to tell deeply affecting stories.

The poems in Before the Great Troubling are direct and spare, remarkable for their clarity. Mesler is not afraid to go for a laugh, but even the funny poems seem to grow from sadness at the root. “I imagine I am always / looking to be stirred / because I am so often shaken,” he writes in “The Observer Observed,” a wry depiction of sexual longing and a typical example of Mesler in his clever mode. Many of the poems leave aside the playful attitude in favor of a more earnest, though never sentimental, voice. The title poem examines the comfort and torment of memory:

There were days when time

There were days when time

did not imprison, did not

glad-hand the devil.

And there was a feeling that this

would all go on, getting

better and better,

enriching us in ways we could never

foresee. This was the feeling

we lived under as if

it were a shade.

Mesler has many a struggling writer’s dream day job: bookseller. He and his wife Cheryl own and operate Burke’s Books in Memphis, a venerable store that has been in business since 1875. Mesler went to work there in 1988, and he and Cheryl bought the place in 2000. It’s a challenging business: “We struggle,” he writes on his website. “Small businesses do and small bookstores do, hellishly.” Even so, he loves selling books, as he reveals in a recent email exchange with Chapter 16, in which he answers questions about the store, his work, and himself.

Chapter 16: Let’s start by talking a bit about you as a bookseller. On the website for Burke’s, you call a bookstore “a place of sympathetic magic.” That’s a wonderful notion. Can you elaborate on it a little? What’s the particular magic that happens in a bookstore?

Mesler: Well, a good bookstore is all about browsing, about discovery. It’s not about calling ahead to have the new Anne Rice novel waiting for you at the counter so you can dash in. I am not anti-Kindle because if it gets more people reading and it makes more money for authors I am all for it. But it would be sad to see browsing die. Not web-browsing, but wandering through a well-stocked bookstore and looking at dust jackets and reading jacket copy and blurbs, feeling the texture of a real paper and boards book in your hand. To me that’s a heady experience. You go in and maybe you wanna look at the new Toni Morrison novel, or the new biography of Joseph Heller. Then you find your fingers, through some recondite impulse, picking up an Anthony Burgess novel, or a Henry Green, or an Iris Murdoch, and it accompanies you to the checkout desk, goes into a sack and goes home with you and, voila, you have a new collaborator in your home, a new puzzle, a new friend. That’s magic.

Chapter 16: You’ve hosted a lot of great writers at the store. Is there a moment from an author appearance that stands out in your memory?

Mesler: The snarky part of me wants to diss one or two of the very few rude writers we have had in our store, but one is dead now and one is a rock star. One expects bad behavior from rock stars. Instead, I remember the beautiful moments of serendipity, of grace, of illumination, that have occurred when we have had seriously great writers visit. For the most part I find writers warm and engaging people. And then there is their art. Writing is akin to godhead. I am a serious and enthusiastic fan of poetry and fiction.

Some highlights among many: hearing Richard Ford read is always astonishing. Hearing Marilynne Robinson do Q&A was awe-inspiring. Hosting Charles Frazier for his first novel about the Civil War, a little book called Cold Mountain, meeting John Lewis and Ralph Abernathy (on separate occasions), Robert Boswell, Isaac Hayes, Archie Manning, Nick Hornby, Ann Beattie, Robert Stone, Peter Carey, and on and on. I know that’s not answering your question but I can’t pick one moment.

I also love having talented friends visit: Steve Stern, Lee Smith, Jill McCorkle, Larry Brown, Buddy Nordan, Peter Guralnick, Audrey Niffenegger, Cary Holladay. But, if I had to pick the most rewarding relationship I’ve had with an author it would, of course, be with John Grisham. He means a lot to our store and to me personally.

Chapter 16: As a bookseller, how do you feel about ebooks and their impact on the business? Could you imagine Burke’s selling ebooks if/when more brick-and-mortar stores start doing that?

Mesler: I guess I sorta answered that. If people are going to read more David Markson or James Joyce or Virginia Woolf or Cormac McCarthy with Kindles, I think that’s great. If authors are going to get more money because of some new-fangled gadget, today’s play-pretty, then that’s wonderful. Serious writers don’t make enough money.

Mesler: I guess I sorta answered that. If people are going to read more David Markson or James Joyce or Virginia Woolf or Cormac McCarthy with Kindles, I think that’s great. If authors are going to get more money because of some new-fangled gadget, today’s play-pretty, then that’s wonderful. Serious writers don’t make enough money.

But, Burke’s selling e-books? No. It is antithetical to what we are at least partly about, which is honoring the book as object. If you love old books with sewn bindings and decorated endpapers and gilt edges and leather covers with raised bands, then the introduction of electronic book devices into that atmosphere might set off some kind of anti-matter paroxysm that would turn the world inside out, if I am remembering my Star Trek correctly.

Chapter 16: Since we’re talking about ebooks, how do you feel about them as a writer? Have you ever considered digital self-publishing instead of working with small indie publishers?

Mesler: Self-publishing, no, that’s not for me. A few of my books are available for Kindle, I believe, but that doesn’t interest me much. I’ve never even seen one of the devices. I love my small indie publishers. They publish me in books made of paper. I want to hug and kiss and thank every one of them.

Chapter 16: You’re a pretty adventurous, experimental writer. Do the multi-media possibilities of digital books—soundtracks, embedded video, etc.—appeal to you at all?

Mesler: No, I am not too interested in those kinds of gimmicks. Am I an experimental writer? I think that’s a lovely compliment. I think I am experimental in a very rudimentary way. It’s like the chemistry set I got as a child. I had no aptitude for scientific knowledge and I hated reading directions so I mixed the chemicals willy-nilly, by color mostly, and got, you guessed it, no results. Sometimes I got a lovely stink. I feel like I experiment with language out of some kind of basic ignorance that is akin to this.

Chapter 16: You said in a recent interview that you don’t think your voice is easy to pin down. Is an identifiable voice a good thing, or do you want to disappear in your work?

Mesler: I want to disappear in my work. I want to disappear period. If I were invisible I could sneak into the girls’ locker-room. Seriously, I think there is a Mesler voice. I think it just shows up in the cracks of whatever form I am experimenting with. And I only try to write a different book each time out because I am interested in all kinds of writing. I’d like to stretch whatever small talent the muses have granted me. And I’d like to keep trying to write that perfect book, the one they will read on Parnassus. I think I answered this question in that recent interview by admitting that my voice could most easily be found in my poetry. I think a distinctive voice, especially perhaps in poetry, is a good thing.

Chapter 16: You’ve been very open about the fact that you suffer from agoraphobia and acknowledged that it helps account for your prolificacy. Beyond that, how has it affected your work? Do you feel its effect on your imagination?

Mesler: This outer-space malady called agoraphobia, or Social Anxiety Disease (which I like for its acronym) only helps me with my output by locking me in my cell. I write a lot because I have more free time than most people. This is both sorrowful and favorable, like much about the writing life. I don’t know that it has affected my work in any psychological way, though that may not be for me to say. I will say this: I was in therapy for a decade with a Jungian Zen dream-interpreting therapist and, while it did not give me the key to my prison, it did open me up in profound and unexpected ways. I traveled deeper into myself than I thought possible and I am very grateful for that.

Chapter 16: What were the first things that sparked your poetic imagination? Can you remember when you first took pleasure in shaping language in a poetic way?

Mesler: I wrote my first poem in fourth grade, a re-wording (read plagiarism) of “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere.” The teacher made over me. And I had a revelation; I thought, attention, yeah, that’s what I want. Really though, honestly, in deadly earnest, I started keeping a journal my sophomore year in high school and have written consistently since then, indeed non-stop since then. Someday I hope to get it right.

Chapter 16: Can you talk a little about poetry you love? Do you have touchstone poems or poets that you return to often?

Mesler: I think the poets I first read in my early twenties, James Tate, Mark Strand, W. S. Merwin, Sylvia Plath, Leonard Cohen, Stephen Dunn, C. K. Williams, really sparked me. I was heavily influenced by all of them, and, except for Plath, they were all still alive and still putting out new books. It was an exhilarating time. Later, William Carlos Williams and John Berryman became heavy favorites and, finally, the discovery of Frank O’Hara’s singular work changed me for all time. I have probably re-read more of O’Hara’s work than any other poet. Now, for touchstones, all these comrades still spur me on, and I also find inspiration in poets like Issa, Basho, Rumi, Hafez. And I could read Yeats’ “The Second Coming” every morning for breakfast for the rest of my course of days.

Chapter 16: The title of the new poetry collection—Before the Great Troubling—has an elegiac flavor, and a lot of the poems do look back, although not necessarily in a mournful way. Did you think of this collection as an engagement with memory when you were putting it together?

Mesler: Yes, that’s exactly what that title and many of its poems reflect, an attempt to make peace with a past that was in some ways simpler and still troublesome. I think, perhaps, writers use their pasts so much because they feel they didn’t get it right the first time. Editing a poem about the past becomes emblematic of editing one’s past. It’s often true of my writing, at any rate. Of course I am fervently trying to edit my youth, which was equally distressing and ecstatic. And, I guess, in reality, I am also trying to edit what I did yesterday, or the day before. I am often re-writing conversations I had with people in the past week. Inside my head there is a congregation of devils and imps and angels and kith and kin.

Mesler: Yes, that’s exactly what that title and many of its poems reflect, an attempt to make peace with a past that was in some ways simpler and still troublesome. I think, perhaps, writers use their pasts so much because they feel they didn’t get it right the first time. Editing a poem about the past becomes emblematic of editing one’s past. It’s often true of my writing, at any rate. Of course I am fervently trying to edit my youth, which was equally distressing and ecstatic. And, I guess, in reality, I am also trying to edit what I did yesterday, or the day before. I am often re-writing conversations I had with people in the past week. Inside my head there is a congregation of devils and imps and angels and kith and kin.

Chapter 16: This may be a chicken-and-egg question, but when you are playing with form, as in a story like “Delitescent Selves,” do you start with the form—It’d be fun to write a story as a book review—or do you hunt down a form that seems to suit a story you want to tell?

Mesler: Hmm. I think, at least with that story, the form came first. In my hippie novel, We Are Billion-Year-Old Carbon, I challenged myself to write a story told entirely in reviews of the Beatles’ albums. I saw their arc, from “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” to “Why Don’t We Do it in the Road” to “Let it Be,” as a journey through a love affair. At first I wanted to sell the idea to a better writer because I thought the form very clever and imagined how fine it would be if someone who was smarter than me wrote it. I still think it turned out OK, though imagine it in the hands of Don DeLillo, or Lorrie Moore, or Steven Millhauser, or Thomas Pynchon. Anyway, now that I think of it, I probably write more from a design, a clever scheme, than the opposite, whatever the opposite of that may be. At least I’d say that’s true of my short fiction.

Chapter 16: Even when your themes are on the serious side, there’s a tremendous playfulness in your writing. You clearly love to play with language, love to corral all kinds of cultural references into you work. Do you feel a sense of play when you’re writing? Do you ever feel that writing is a slog, as so many writers do?

Mesler: Thank you. I take that as a significant commendation. When I am writing at my best I am playing. I don’t feel that writing is a slog, hardly ever. I think it is a great and challenging game and I have always loved games. I like pretty much every stage of it, the initial inspiration, the struggle to tell it the best way you can, the epiphanic discoveries along the way, even the revising. And, just entre nous, the best thing someone can tell me about something I’ve written is that he or she thought it very funny. Maybe I want to be Woody Allen instead of Joan Didion. Robert Louis Stevenson said, “Fiction is to grown men what play is to a child.” Keeping that inner child alive, I believe the headshrinkers will tell you, is perilous and fraught with devils, but it is also, often, a lot of fun.

Corey Mesler will read and sign Before the Great Troubling and Notes Toward the Story & Other Stories at Burke’s Books on September 15 at 6 p.m.