For Something Other Than Himself

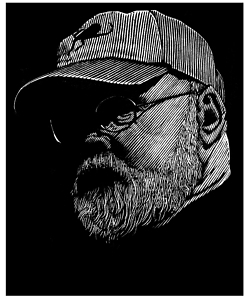

Renowned illustrator and book artist Barry Moser reflects on his work

Editor’s note: Franklin artist Carolyn Beehler recently interviewed acclaimed illustrator, printmaker, and book artist Barry Moser, a Chattanooga native. This excerpt of their conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity (but a bit of frank language remains).

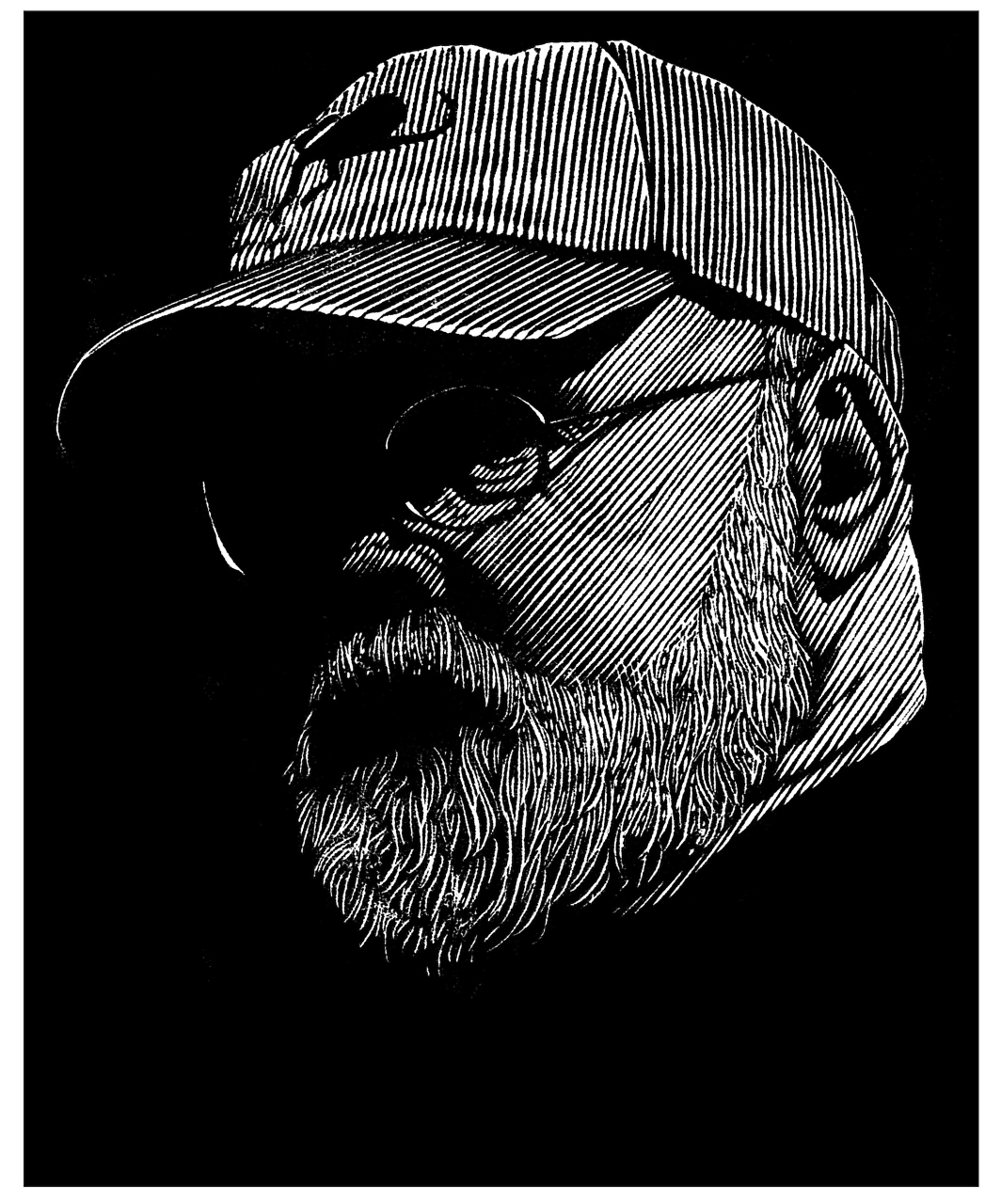

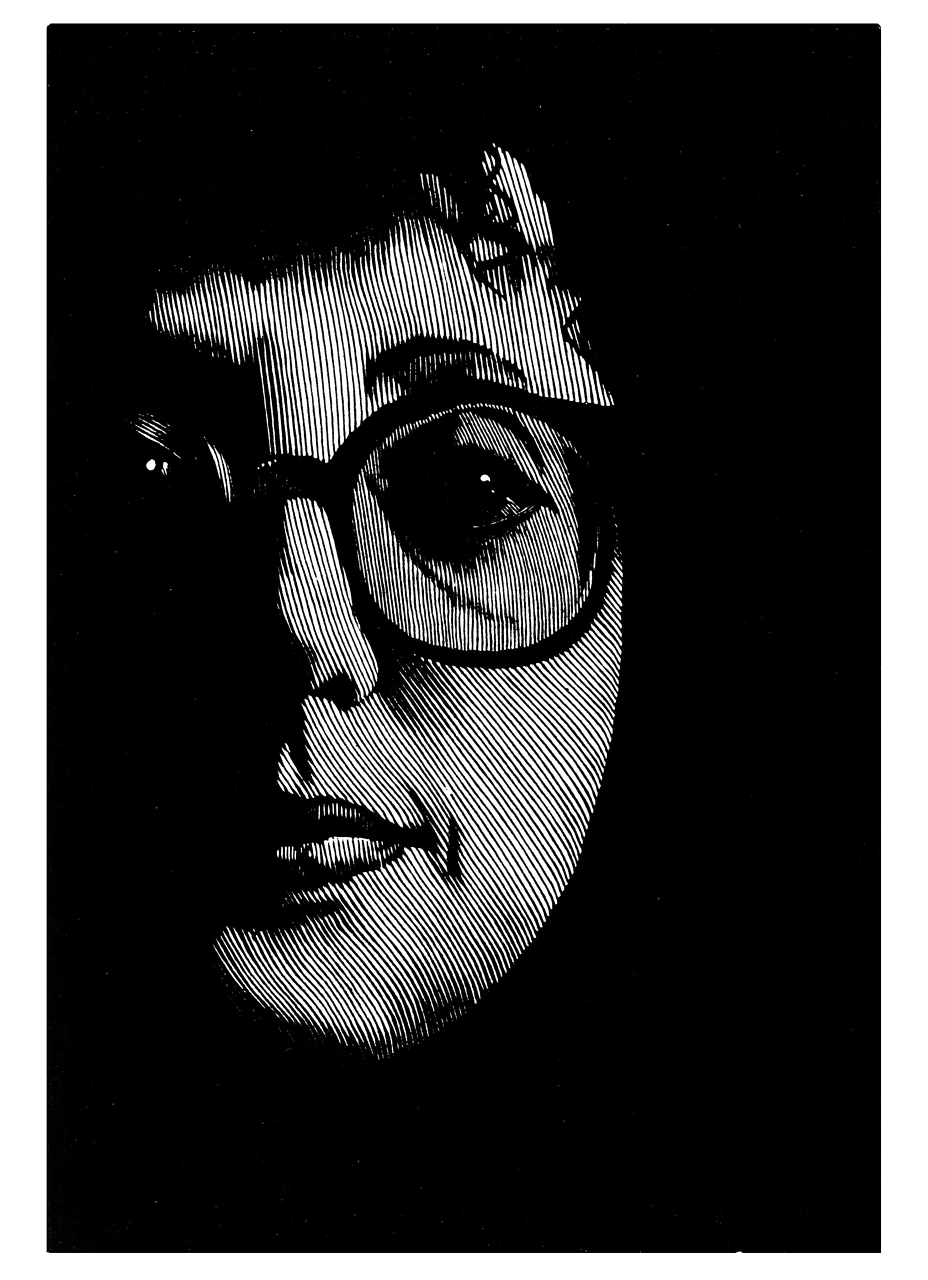

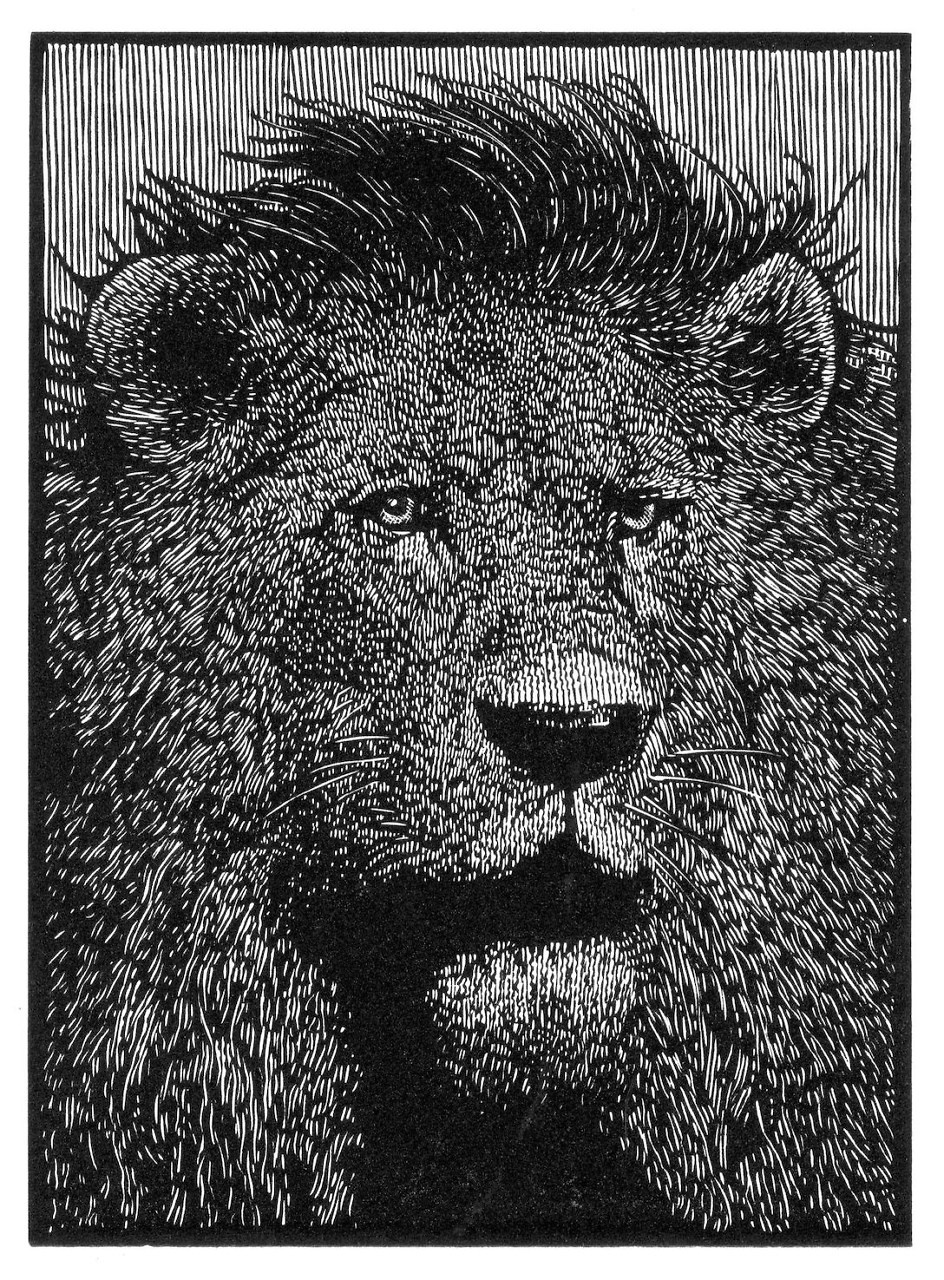

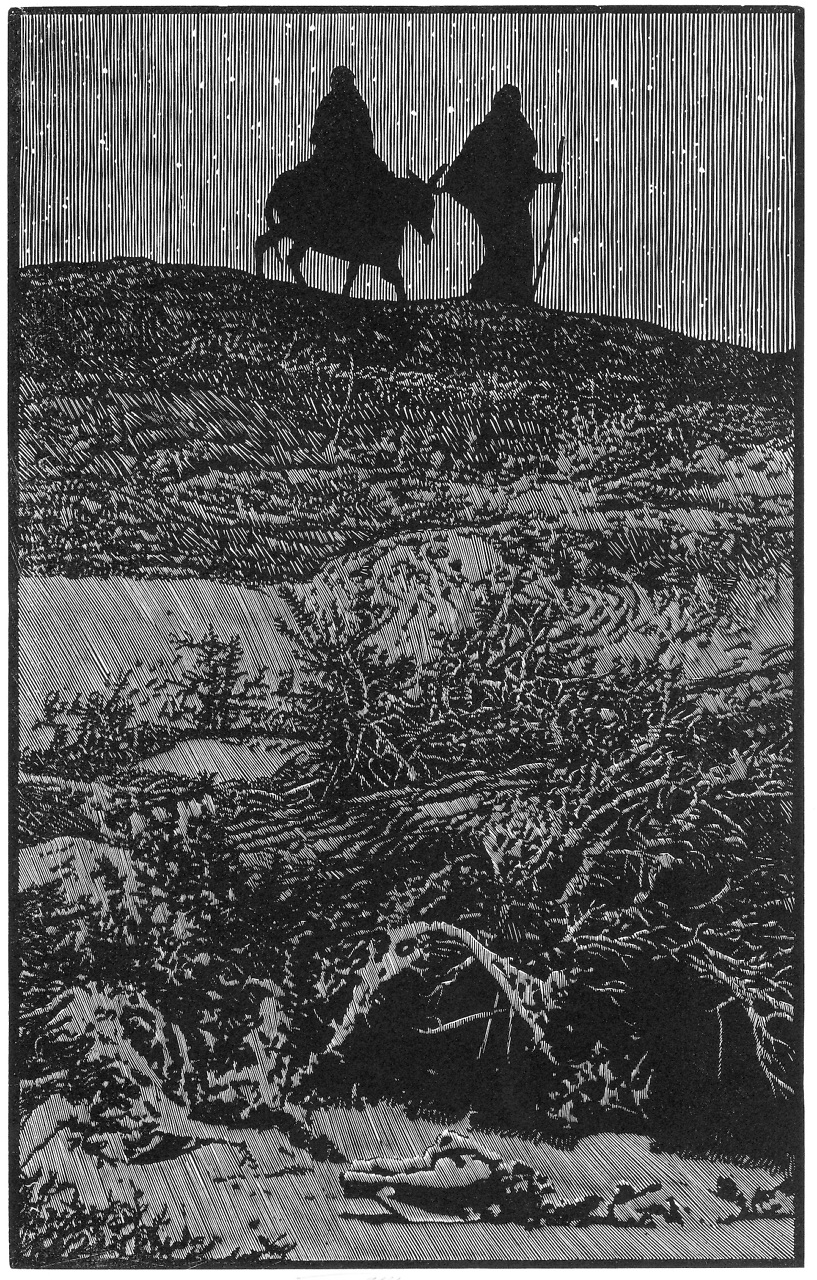

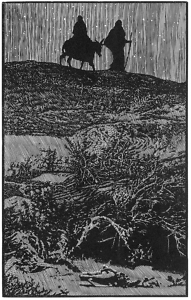

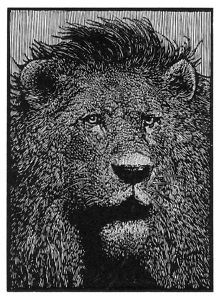

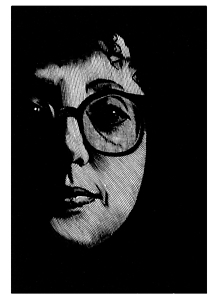

They say you shouldn’t meet your heroes, which is good advice, but what a gem I would have missed out on had I not reached out to Barry Moser. Barry is a bookmaker, one of the world’s most marvelous illustrators, and a gifted writer. Through his Pennyroyal Press, he has created acclaimed editions of many books, including Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Huckleberry Finn, The Wizard of Oz, and the Pennyroyal Caxton Bible. He’s well known for his portraits of literary greats such as Eudora Welty, John Updike, and Joyce Carol Oates.

Though a Southerner at heart, he feels most at home surrounded by his books in Northampton, Massachusetts. After the tremendous success of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, he treated himself to his own dream library with a hearth, medieval sword reproductions, and cherry wood shelves full of fiction and nonfiction books on topics like typography, art history, and definitely food. (He has at least 700 cookbooks.)

You don’t just drop by with Barry because he’s got “a jaw that just keeps on going,” but even after three hours on the phone I wish I could have stayed for dinner.

Carolyn Beehler: What are your convictions as an artist? Where do you think they come from?

Barry Moser: I only have two. Both of them are rooted in my own experience, of course, but they’re also rooted in [the work of] Miss Flannery O’Connor: First, to see and not look away. And two, to work. Those are my two obligations.

Beehler: What analogy would you give if you had to describe the art world to a 9-year-old?

Beehler: What analogy would you give if you had to describe the art world to a 9-year-old?

Moser: If it were my grandchildren — I got 10 of them — I’d say, “Well, honey, I think that’s a pile of horseshit.” Because that’s the way I talk to my grandchildren. It’s really hard for me to offer opinions because I just think that so much of 20th-century art, the big name, blockbuster gallery art of the 20th century, was a product of a generation — several generations — who were just simply lost.

World War I started it all. Well, it started before that with some of the German Expressionists and all, but still, that war which continued on to be World War II and then from there into Korea and Vietnam, it’s a lost generation and a lost century.

Beehler: What made us particularly lost, as opposed to other generations?

Moser: Well none of them had the atomic bomb. I think it’s the anxiety of the possibility of annihilation that fosters a lot of that. And nihilism.

And that brings me to another malady that you didn’t ask me about, and that is ego. The center place that ego plays in art in the 20th and 21st centuries is to me abominable. You look at one of my favorite paintings in the whole world, I think it’s 14th, could be 15th century…the, um…. [breaks off laughing]. I can see it: It’s a pieta by the Master of Devingnon. It’s an incredibly abstract composition with the body of Christ laid out horizontally on Mary’s lap, right arm perpendicular to his body. And it’s black and white and a cobalt gown and a lot of gold leaf. It’s absolutely, to me, stunning. Breathtaking. And I’m pretty sure that if I were ever to see it in person, I would die crying. My point is not the painting so much as the fact that we don’t know who did it. He was doing that painting for someone other than himself. And that’s the thing that I think is missing so much from contemporary art. Most artists today are ego driven.

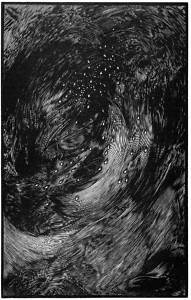

I can’t say that I’m lacking in ego, but my work is driven by something other than the desire for fame and riches, and if nothing else I hold up the almost 300 illustrations I did for the Bible and not just the images but the Bible itself — the typography, the design, or the production and all of that — that was a project I did for something other than myself.

Beehler: How did you find the stamina for 12-hour workdays during your production of the Holy Bible?

Moser: We’re entering into almost a different realm. I still don’t quite understand that myself. I did it, there’s a documentary on it, ‘course the book itself is sittin’ out there. It’s real, it’s done. Albeit that I am a devoutly religious agnostic, that opens up for me the play of other forces than those we are aware of. I just don’t know! Which is of course what agnostic means. I just don’t know. But it came from somewhere, and I was able to do it, and I have to say here, too, that my ability to be able to do that was because I had somebody picking up all of the expenses. It cost $2 million.

We had all of the paper made for us. The paper that most of the bibles were printed on was made for us in Germany, sheet by sheet with our own watermark. Each book is a goat, so we were the instigators of the slaughter of about 700 goats.

You can go out there and buy yourself a single-wide [trailer] for $20 or $25,000. It gives you everything you need. You have a roof over your head, heat we hope, and you’ve got a place to sleep. So your needs are met. But you can also do something, build something, that meets those same needs for $6 or $7 million. And what’s the difference? The difference is in the materials that you’re using, the scale of the thing that you’re doing, and the craftsmanship that goes into it. [In other words, it’s the best way a book can be made, which explains why each Pennyroyal Caxton Bible costs $12,500. C.B.]

You can go out there and buy yourself a single-wide [trailer] for $20 or $25,000. It gives you everything you need. You have a roof over your head, heat we hope, and you’ve got a place to sleep. So your needs are met. But you can also do something, build something, that meets those same needs for $6 or $7 million. And what’s the difference? The difference is in the materials that you’re using, the scale of the thing that you’re doing, and the craftsmanship that goes into it. [In other words, it’s the best way a book can be made, which explains why each Pennyroyal Caxton Bible costs $12,500. C.B.]

Beehler: You make books, so it would make sense that you enjoy libraries and bookstores. Describe your dream bookstore, with money being no object?

Moser: Wood, a lot of dark wood, stacks that would be 8 to 10 feet high, ladders that travel on casters. It would be carpeted [and have] unobtrusive, classical music like chamber music. It would be not too big, not too small. Employees would know books (no computers to look up titles like Barnes & Noble). It would be well lit, with tables and lovely cushioned armchairs (no beanbags), a rare books section that would be about half the store, and a children’s section, to indoctrinate them into good books. It would be egalitarian. And there’d be a loft. And a literary café next door.

It’s funny because my second wife and I — she’s a bookseller — met at Lemuria bookstore in Jackson, Mississippi. And Lemuria is one of the best bookstores in America. People have a hard time believing that when I say that. [mimicking people] “In Mississipp?” And I say, yes, in Mississippi. I was down in Jackson, and in this airport there was this t-shirt —I kick my ass for not buying it — but the front of it said, “Yes, we read in Mississippi” and on the back it said, “Some of us even write.” And then it’s all the Mississippi writers.

Beehler: How important is it for an artist to have an apprenticeship?

Moser: The South has a little bit of an inferiority complex. People think they have to go to New York to do well and it’s bullshit. It’s just not so. You don’t have to go to New York. There’s just no reason that you really have to unless you want to be part of the world that Tom Wolfe wrote about [in The Painted Word].

Myself, rather than dealing with the Leo Castelli Gallery there — I’m not sure I got his name right — rather than that and the gallery world of New York, I’d much rather be invited to be part of an exhibit at The Morgan Library.

Beehler: Any dream projects, artistic or otherwise?

Moser: Good God, where to start. If it were possible, I would die with delight to be able to do Wise Blood. But it’s not possible. Not right now, and I won’t live long enough to see when it would be possible. When it goes into public domain there’s nothing that the O’Connor family can do about it, but until that happens the O’Connor family won’t let anybody touch it. I’ve investigated.

I’ve written I think five, maybe not even that many, fan letters in my life, and they’ve all been written to writers. And the first one I wrote was to Jayne Anne Philips. She is originally from West Virginia, kind of a Southerner but it depends on how you count it. And I’d just read I think my second collection of her stories and I was enthralled. So I wrote her a fan letter, and at the end of the letter I said I dare not assume that you know my work or anything, but I do fine books and if you have sometime something that you would like to see in that sort of a presentation, let me know. So it was a Sunday morning and the phone rang and it was she. She said, “Ok, so tell me why you think I would want you fucking around with my book?” And that was the beginning of a real sweet friendship, and I’ve never done a book with her and I dare say I probably never will.

I’ve written I think five, maybe not even that many, fan letters in my life, and they’ve all been written to writers. And the first one I wrote was to Jayne Anne Philips. She is originally from West Virginia, kind of a Southerner but it depends on how you count it. And I’d just read I think my second collection of her stories and I was enthralled. So I wrote her a fan letter, and at the end of the letter I said I dare not assume that you know my work or anything, but I do fine books and if you have sometime something that you would like to see in that sort of a presentation, let me know. So it was a Sunday morning and the phone rang and it was she. She said, “Ok, so tell me why you think I would want you fucking around with my book?” And that was the beginning of a real sweet friendship, and I’ve never done a book with her and I dare say I probably never will.

It’s hard to do because I work for royalties, and a writer works for royalties, and she’s not gonna wanna give up her royalties to me, or part of her royalties to me, and a publisher is not gonna pay her 10 percent and me 10 percent, ya know? So it just doesn’t work. I have worked with a lot of contemporary poets, ’cause poetry’s, that’s a horse of an entirely different color. Poets wanna get their poems published.

I have had the great pleasure of working with Eudora Welty. I did a book with her which was an absolute joy because she was really, really good to work with.

[Read Chapter 16‘s review of Barry Moser’s 2015 memoir, We Were Brothers, here.]

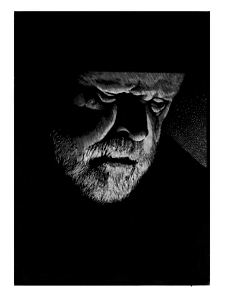

*All images by Barry Moser. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

Copyright (c) 2020 by Carolyn Beehler. All rights reserved. Carolyn Beehler is a paper artist living in Franklin. After graduating from art school she spent the rest of her 20s traveling and improving her art. In 2016, she held her first show called “Frolics in Italy.” Carolyn has been featured in group shows and publications around Nashville. Her latest collection reflects on her experiences living in China. In her free time, she enjoys meeting and writing about her favorite artists.