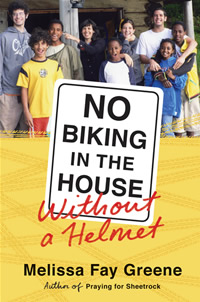

A Happy Family, Supersized

Acclaimed journalist Melissa Fay Greene delivers a witty account of her exceptional family

Journalist Melissa Fay Greene and her attorney husband, Don Samuel, are the sort of people who truly love living in a full house. As Greene writes in her new memoir, No Biking in the House without a Helmet, “Donny and I feel most alive, most thickly in the cumbersome richness of life, with children underfoot.” Plenty of couples say the same when their children actually are underfoot but nevertheless look forward to an empty nest and the intermittent joy of grandchildren. For Greene, however, the prospect of being home alone after her four children grew up was not a happy one. After a miscarriage at age forty-five, Greene decided to seek a child through the complex process of international adoption, with her husband’s encouragement and her own considerable investigative skills. No Biking in the House tells the story of how her family ultimately welcomed five new children—a son from Bulgaria, and three sons and a daughter from Ethiopia—and found their lives “enlivened and enriched” in the process.

Greene—a two-time finalist for the National Book Award in nonfiction and the bestselling author of Praying for Sheetrock, the story of a civil-rights struggle in small-town Georgia—began her search for a child on the Internet. In the wry, breezy tone she employs throughout the book, she conveys the fraught uncertainty of sizing up a neglected, institutionalized youngster from half a world away, with nothing more to go on than an agency’s description. “The write-ups sounded like the Sky Mall catalog,” she writes. “Were the agencies trying to inform or to deceive? Hi Forever Mommy and Daddy! My name is Vladimir! I am a sociopath with big blue eyes who loves teddy bears, herring, and arson!” Greene snags a magazine assignment on doctors who specialize in evaluating children for international adoption, hoping to glean knowledge for her own quest. Still full of doubt and telling herself she is only doing research for the article, she travels to a Bulgarian orphanage to meet the four-year-old boy who will become her first adopted child.

The chapters devoted to the adoption of this child—originally called Christian, later renamed Jesse—are the most engaging in this lively book. In spite of being developmentally delayed by his long stay in the bleak orphanage, Jesse is a bright and affectionate child, and Greene does a great job of conveying her realization that cold-eyed calculation is impossible when confronted with “one small boy saying ‘Mama’ with disbelieving happiness.” She doesn’t shy away from describing the difficult adjustment once Jesse is at the family’s Atlanta home, where his tantrums and incessant demand for her attention make everyone miserable. Jesse eventually settles into his new home, but not before Greene makes a furtive telephone call to the adoption agency to ask, “What are you supposed to do if you’re not sure you can really do this?” Things go more smoothly with the Ethiopian children, though homesickness and the cultural divide provide some challenges.

The chapters devoted to the adoption of this child—originally called Christian, later renamed Jesse—are the most engaging in this lively book. In spite of being developmentally delayed by his long stay in the bleak orphanage, Jesse is a bright and affectionate child, and Greene does a great job of conveying her realization that cold-eyed calculation is impossible when confronted with “one small boy saying ‘Mama’ with disbelieving happiness.” She doesn’t shy away from describing the difficult adjustment once Jesse is at the family’s Atlanta home, where his tantrums and incessant demand for her attention make everyone miserable. Jesse eventually settles into his new home, but not before Greene makes a furtive telephone call to the adoption agency to ask, “What are you supposed to do if you’re not sure you can really do this?” Things go more smoothly with the Ethiopian children, though homesickness and the cultural divide provide some challenges.

Greene makes no claims to be a supermom, but No Biking in the House reveals a devoted mother with traditional ideas about discipline and family harmony. When her eldest biological daughter begins to dabble in punk culture, Greene quickly pulls the girl out of public school and enrolls her in an Orthodox Jewish school. Greene engages in an epic battle with Helen, her Ethiopian daughter, over a forbidden sip of Coke. She agonizes when two of the boys stop speaking to each other after a squabble.

Family unity is a core value for Greene, and it’s clear that, although Greene and Samuel respect the birth cultures of their adopted children, they want their blended family to be as homogeneous as possible. Before deciding to adopt two Ethiopian brothers, eleven and eight, Greene sits them down and tells them they will have to convert to Judaism. The boys have been raised as Ethiopian Orthodox Christians and are already rather devout, but they eagerly agree. Greene understands their motivation: “These children just really wanted a new family,” she writes.

This is one of the few moments in the book where Greene touches on her direct experience of the cultural costs of international adoption, though, like most adoptive parents, she seems to have given the issue a lot of thought. In a long passage, Greene ponders whether love can “make up for the complicated web of connections lost to the child through international adoption,” and considers what she would want for her own child if circumstances were reversed. She advocates for raising the adopted child in a diverse environment that includes elements of the birth culture but argues that ultimately children should be taught that their truest selves are “deeply their own, independent of all borders.”

This is one of the few moments in the book where Greene touches on her direct experience of the cultural costs of international adoption, though, like most adoptive parents, she seems to have given the issue a lot of thought. In a long passage, Greene ponders whether love can “make up for the complicated web of connections lost to the child through international adoption,” and considers what she would want for her own child if circumstances were reversed. She advocates for raising the adopted child in a diverse environment that includes elements of the birth culture but argues that ultimately children should be taught that their truest selves are “deeply their own, independent of all borders.”

While Greene doesn’t ignore such serious concerns, nor hold back from describing the grim conditions in the orphanages where she found her adopted children, most of No Biking in the House Without a Helmet is thoroughly upbeat, filled with funny, affectionate anecdotes about the nine kids. Greene is a brisk writer, not afraid to be a bit irreverent, and the whole family comes across as sweet, smart, and full of goodwill. If the book has a flaw, it’s a fond mother’s tendency to assume that all stories about her children are equally interesting. Still, Greene’s love and good humor are hard to resist, and most readers will find No Biking in the House Without a Helmet heartwarming fun.

Melissa Fay Greene will appear at the 2011 Southern Festival of Books, held October 14-16 in Nashville.