A Hero’s Journey

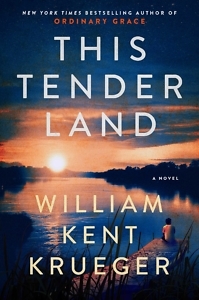

Four orphans search for answers in William Kent Krueger’s This Tender Land

Odysseus “Odie” O’Banion can’t imagine how life could get worse. He is an orphan. He’s punished by his school’s headmistress almost daily, and his beloved harmonica is in constant peril from the school’s sinister disciplinarian. Then events beyond Odie’s control make things worse — much worse. This Tender Land by William Kent Krueger follows Odie and his friends as they run for their lives through Depression-era Minnesota, venturing beyond all they’ve known to find answers to questions they can’t stop asking.

A follow-up to Krueger’s Ordinary Grace, an Edgar Award winner in 2014, This Tender Land also centers around the internal lives of young people. Though the novel is framed by the voice of an elderly Odie O’Banion, who lends a sagacious perspective to the narrative, most of the book moves chronologically in real time from young Odie’s perspective.

Odie and Albert O’Banion wind up in Lincoln Indian Training School, run by the vindictive headmistress Mrs. Brickman, after their moonshining father gets gunned down nearby. Their mother died years before, and their only blood relative — an aunt in St. Louis — makes no move to take them in. Amidst the school’s harsh conditions, the brothers must forge a new community. Their best friend, a mute Sioux baseball player named Mose, and a kindhearted German maintenance man become their substitute family. A generous farming widow named Cora Frost steps in as a maternal figure, and the O’Banions take a brotherly interest in Cora’s six-year-old daughter, Emmy.

Even with this ragtag group of friends, conditions in the school are brutal. Odie spends countless hours locked in a room without food as punishment for defending other classmates from the abuses of Mrs. Brickman, affectionately referred to by the students as “The Black Witch,” who had “the darkest heart of anyone I’d ever known,” reflects Odie. When the abuse reaches a fever pitch, the O’Banions, Mose, and Emmy are forced to run away, an event the local newspaper erroneously reports as kidnapping. What could be worse for orphans than an understaffed boarding school with an inadequate food supply and an evil headmistress? Being homeless in Depression-Era Minnesota with a kidnapping bounty on their heads.

As the group begins to journey toward the O’Banions’ long-silent aunt in St. Louis, the young travelers must rely on each other’s strengths to survive: Albert is careful and calculating, managing the group’s funds and travel arrangements. Mose is physically strong and intuitive. Emmy, still just a little girl, has clairvoyant dreams. And Odie—well, Odie can play the harmonica.

As the group begins to journey toward the O’Banions’ long-silent aunt in St. Louis, the young travelers must rely on each other’s strengths to survive: Albert is careful and calculating, managing the group’s funds and travel arrangements. Mose is physically strong and intuitive. Emmy, still just a little girl, has clairvoyant dreams. And Odie—well, Odie can play the harmonica.

Travelling down the Mississippi by canoe, camping in the open air and eating when they can, the crew creates safety for one another. “Albert and Most pushed us along through the dark,” Odie recalls, “all I could think about was what I’d gained, which I thought of then as freedom.” Along the way, the kids meet a cast of colorful and questionable characters. They learn to lean on each other’s intuition to find their way. Should they trust the drunken, one-eyed farmer? The Native American tracker? The beautiful, jazz-singing faith healer?

Isolated before leaving Lincoln School, the children encounter the effects of the Great Depression for the first time when Odie runs across a Hooverville. As he ambles through the pieced-together lean-tos and the kettles of boiling leaves, Odie encounters a family who is needier than he is — a first. Will he share his group’s limited resources against their wishes, or will he remain loyal to his chosen family?

The opportunity to help others coupled with the experiences of their journey change Odie and his crew forever in this coming-of-age story. An older Odie leaves readers with these words in the final chapter, “Perhaps the most important truth I’ve learned across the whole of my life is that it’s only when I yield to the river and embrace the journey that I find peace.”

Sarah Carter holds an M.F.A. in creative writing from the Sewanee School of Letters.