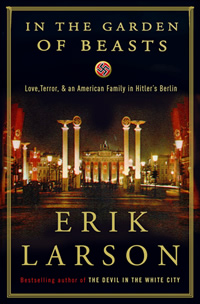

"A Horde of Criminals and Cowards"

In Erik Larson’s new book, the U.S. ambassador tells the truth about Hitler’s Germany—even if Roosevelt doesn’t want to hear it

In June 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed a mild-mannered, bookish historian from the University of Chicago, William Dodd, as his new ambassador to Germany. Dodd wasn’t Roosevelt’s first choice, nor was he an obvious one: a lifelong academic who was writing a multivolume history of the antebellum South, Dodd was chosen simply because he had a doctorate from the University of Leipzig—where he wrote his dissertation on Thomas Jefferson—and spoke fluent German.

The problem was, as Erik Larson demonstrates in his captivating new book, In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin, the Germany Dodd had known at the turn of the century—conservative, orderly, intellectual—was in the throes of a revolution, at once radical, chaotic, and populist. By the time Dodd arrived in Berlin with his wife and two grown children, the country he had loved was almost completely gone, and he would spend his four-year term as ambassador trying to figure out what had gone wrong.

As was the case with most foreign observers in the early days of Hitler’s Germany, it was not immediately obvious to Dodd that anything was wrong in the first place. Despite having fought a war with the country just fifteen years earlier, many Americans in the 1930s sympathized with Germany and opposed what they saw as an overly punitive restitution forced on it by France and Britain. Tens of millions of people still identified as ethnic Germans, who knew from still-living relatives in places like Dusseldorf and Hamburg just how rough the 1920s had been for the country. Not knowing what was to come, they saw Hitler’s talk of a new German order as an acceptable, if not entirely respectable, corrective to the years of economic and social tumult.

True, Hitler and his followers spoke menacingly about Jews and the alleged power they held over the economy and the government. Then again, so did many Americans—not as crudely as the Nazis, perhaps, but enough to let them ignore what should have been an obvious warning sign. And they wanted to ignore it because, above all, Americans in the 1920s and ’30s were profoundly isolationist. After the deadly farce of World War I, they wanted nothing to do with European politics. And if that meant looking away while a few Jews and communists got knocked around by Brownshirts, okay.

Dodd encountered yet another kind of self-delusion within the diplomatic ranks. Staffed by either wealthy Roosevelt allies or stuffy New England elites, the American diplomatic establishment was allergic to controversy. They regarded it impolite to look too closely or critically at another country’s internal affairs, as if Germany were no different from those eccentric neighbors down the Cape Cod shoreline.

Dodd encountered yet another kind of self-delusion within the diplomatic ranks. Staffed by either wealthy Roosevelt allies or stuffy New England elites, the American diplomatic establishment was allergic to controversy. They regarded it impolite to look too closely or critically at another country’s internal affairs, as if Germany were no different from those eccentric neighbors down the Cape Cod shoreline.

Not that Dodd was a militant moralist. He came to the job willing to give Hitler the benefit of the doubt. But precisely because he had been away from Germany so long, the depths to which the country had already fallen—dissenters banished to prison camps, Jews and foreigners being attacked in broad daylight—quickly soured him on his hosts. “I had at least hoped to find some decent people around Hitler,” he told a German society columnist. “I am horrified to discover that the whole gang is nothing but a horde of criminals and cowards.”

With other ambassadors, Dodd organized unofficial diplomatic boycotts of Nazi rallies. He sent blistering cables back home. And he wrote voluminous private letters and diary entries, which provide Larson with an astoundingly in-depth picture of both the man and his unique circumstances.

Larson is also fortunate to have an equally large archive from Dodd’s daughter, Martha. A flirty, attractive woman in her early twenties, Martha was barely separated from her husband when she began affairs with Carl Sandburg and, reportedly, Thornton Wilder; in Germany she took up with handsome mid-level Nazi officials, French diplomats, and Russian attaches. Young and naïve, she reveled in the pageantry and luxury of upper-level Nazi life, and for years she refused to see the vast underside that her father was already documenting. “You always see the bad things,” she told a friend who criticized the Hitler regime. “You should try to see the positive things in Germany.”

Eventually even Martha turned against Hitler’s Germany, in part because of an affair with a Russian diplomat and, unbeknownst to her, spy named Boris Winogradov. Not until she had been there for almost a year did she declare—and then only in her diary—that “the most complicated and heartbreaking system of terror ruled the country and repressed the freedom of the people.” Larson could not have asked for a better figure with which to represent the world’s naïve, belated horror at the Nazi regime than Martha Dodd.

The literature on the rise of Nazi Germany could fill a small library, and there is no end of classic accounts of everyday Germans watching their world close in on them, including classics like Sebastian Haffner’s Defying Hitler and Bernt Engelmann’s In Hitler’s Germany. But because many of these are either written in the first person or by people, like Engelmann, who lived through the regime, there is an inherent bias to see every part of life in 1930s Germany as a step toward World War II and the Holocaust.

The literature on the rise of Nazi Germany could fill a small library, and there is no end of classic accounts of everyday Germans watching their world close in on them, including classics like Sebastian Haffner’s Defying Hitler and Bernt Engelmann’s In Hitler’s Germany. But because many of these are either written in the first person or by people, like Engelmann, who lived through the regime, there is an inherent bias to see every part of life in 1930s Germany as a step toward World War II and the Holocaust.

What Larson has uncovered, and brought to life, in the writings of Dodd and his family is a wholly new perspective: that of an intelligent but otherwise average American family confronting the first years of the Nazi horror. For those who wonder, “What would I have done in that situation?” Dodd is as close to a historical avatar as you’re likely to find. The story practically writes itself.

That’s a good thing, given that Larson is prone to hyperbolic, breathless writing. Few scenes end without a bit of tension-deflating foreshadowing; of a couple with “a gift for gathering loyal and compelling friends,” Larson writes, “The idea that one day it would kill them would have seemed… laughable.” The book would be immensely better if he had simply skipped the last paragraph of each section.

Nevertheless, Larson displays a deft control over the historical material without ever losing the thread of his narrative or diving into quasi-academic didacticism. He’s not content with simply telling Dodd’s story; he’s also using his up-close perspective to frame a unique take on the internal tensions that made the early Nazi state look more like competing Mafia families than the uniform, hyper-efficient totalitarian regime we think of today. It would become that, but only after the turf battles ended.

Eventually Dodd was done in by enemies in the State Department establishment, men who felt he was too hard on Hitler, or too unskilled in the diplomatic arts, or simply lacking the proper bluish hue in his arteries. In 1937, after one too many anti-Hitler cables back home, Roosevelt forced him to resign. He died in 1940, his multivolume Southern history still incomplete.

Erik Larson will discuss and sign In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin at the Nashville Public Library on May 10 at 6:15 p.m. as part of the Salon@615 series.