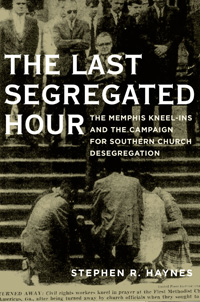

A House of God, Divided

Stephen R. Haynes’s study of the 1960s campaign to desegregate the Second Presbyterian Church in Memphis provides a balanced perspective on a vital element of the civil-rights movement

So many communities, institutions, and elements of everyday life were affected by the civil-rights movement that there’s an almost endless series of individual moments worthy of analysis. The key to any good history of desegregation is the ability to highlight the unique circumstances of any one incident without losing sight of the general social transformation it was a part of. Rhodes College professor Stephen R. Haynes has managed to do exactly that in his new book, The Last Segregated Hour, which provides a thorough and engaging overview of how the struggle to integrate the Second Presbyterian Church (SPC) in Memphis both shaped and reflected the larger concerns over race and religion in 1960s America. Haynes also manages to thread another needle that civil-rights historians often struggle with: he recognizes that even though moral and racial justice were assuredly on the side of the protestors, not all those who opposed them were brutal, billy-club-wielding racists.

The book consists of four sections, which feature the broader context for civil-rights campaigns targeting Southern churches, the particular events in Memphis, the protests at SPC as recalled by those who experienced them, and the aftermath of the campaign. In describing each of these elements, Haynes relies on a combination of newspaper reports, oral-history interviews, and official church records. The great strength of this approach is that he rarely has to insert his own voice into the narrative, instead allowing the events and individuals to speak for themselves.

The book consists of four sections, which feature the broader context for civil-rights campaigns targeting Southern churches, the particular events in Memphis, the protests at SPC as recalled by those who experienced them, and the aftermath of the campaign. In describing each of these elements, Haynes relies on a combination of newspaper reports, oral-history interviews, and official church records. The great strength of this approach is that he rarely has to insert his own voice into the narrative, instead allowing the events and individuals to speak for themselves.

Haynes begins with a consideration of why desegregation campaigns at Southern churches had such a powerful emotional impact. Ultimately, he argues, it is “difficult for people to forget, let alone excuse, what they perceive as immoral behavior on the part of church representatives.” Thus, the racial history of SPC has remained front and center in Memphis’s civic consciousness. According to James Laue, one of the activists Haynes profiles, such was the status of churches in the lives of white Southerners that exposing the moral flaws of a place like SPC was “the ideal path into the [white] collective conscience.”

The main events Haynes covers took place from the spring of 1964 to the middle of 1965. During that time, interracial groups of protestors—many of them from nearby Southwestern at Memphis (now Rhodes College)—began to present themselves at the doors of SPC and seek admission to Sunday services. For over a year, their requests were denied, leading ultimately to generational and theological tensions within the church, national media attention, a revocation of SPC’s right to host the 1965 Presbyterian General Assembly, and finally a congregational revolt within SPC that ended its policy of racial exclusion and prompted the founding of a breakaway Independent Presbyterian Church that would retain a whites-only policy until the mid-1980s.

These events took place within a context of church protests throughout the South—especially in Atlanta, Savannah, and Albany—during the early 1960s. To supporters, the protests were an attempt to live up to Christ’s message of universal inclusion, an attempt to establish the right of all Christians to worship at any altar they chose. Opponents argued that they were “not dramatic moral gestures, but political stunts” performed by activists with no real intention of joining the congregation for spiritual worship. Haynes’s assessment of these differing perspectives is a good example of the generally balanced approach he takes throughout, for while he demonstrates that racial prejudice was at the core of most objections to integrated worship, he also notes that the protestors actually weren’t interested in joining the churches. It was, he notes, “very unlikely that African-Americans in Memphis would leave their own churches to be part of a white congregation, particularly one they had learned to despise.”

These events took place within a context of church protests throughout the South—especially in Atlanta, Savannah, and Albany—during the early 1960s. To supporters, the protests were an attempt to live up to Christ’s message of universal inclusion, an attempt to establish the right of all Christians to worship at any altar they chose. Opponents argued that they were “not dramatic moral gestures, but political stunts” performed by activists with no real intention of joining the congregation for spiritual worship. Haynes’s assessment of these differing perspectives is a good example of the generally balanced approach he takes throughout, for while he demonstrates that racial prejudice was at the core of most objections to integrated worship, he also notes that the protestors actually weren’t interested in joining the churches. It was, he notes, “very unlikely that African-Americans in Memphis would leave their own churches to be part of a white congregation, particularly one they had learned to despise.”

Second Presbyterian was under constant pressure not just from protestors in Memphis but also from the leadership of the Presbyterian Church of the United States (PCUS), which had denounced segregation after the Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954. There was tension within the SPC congregation itself. Most of the church’s Elders favored maintaining segregation, while the junior deacons wanted the church to accept all worshippers. The senior pastor, Jeb Russell, presents a particularly fascinating figure. As the brother of U.S. Senator Richard Russell, a high-profile opponent of civil-rights legislation, Russell might have been expected to side with his Elders. Indeed, his long silence during the protests of 1964 suggested tacit sympathy for their approach, though many protestors also recalled Russell as very friendly to them even as they were denied entry to his church. In January 1965, however, Russell openly broke with SPC Elders in a sermon, saying “we can’t serve Christ with shut doors about the Cross.” This dramatic intervention proved to be the catalyst for a change in policy that resulted in SPC’s first black members by the spring of 1965.

From Presbyterian seminarians and out-of-state sympathizers to Southwestern students and local NAACP activists, Haynes provides vivid profiles of the movement’s key figures. Some received enthusiastic support from their parents, others met with hostility or fear. Jacquelyn Dowd, then a student at Southwestern and now an eminent civil-rights historian, recalls an “icy and hostile” reaction from college administrators when she took part in the protests. The full range of motivations and responses Haynes describes illustrates just how fluid and complex the situation was—far more than a simple struggle between “good” and “evil.”

This last point is also the main theme of Haynes’s concluding section, which considers the development of SPC and its offshoot, the Independent Presbyterian Church, to the present day. Addressing past racial failings is difficult, and signs of progress seem always to be accompanied by continuing signs of recalcitrance. Both SPC and the Independent Presbyterian Church have taken active steps to re-engage the diverse population of Memphis as a whole, often successfully, but these efforts are always shaped by continuing mistrust because of their stands during the 1960s. As late as 2007, and even while partnering with urban churches to address issues of racial inequality, the pastor of Independent Presbyterian Church was forced from the pulpit following a sermon in which he called on his congregation to consider opposition to interracial marriage a sin.

This refusal to deny the moral ambiguity of the SPC legacy coupled with extensive research and a crisp writing style make The Last Segregated Hour an essential read for anyone seeking to understand either the particular racial history of Memphis and SPC or the general impact on American communities of people being forced to react, as Haynes writes, “to a social revolution they could not resist.”

Stephen R. Haynes will discuss The Last Segregated Hour at The Booksellers at Laurelwood in Memphis on January 22 at 6 p.m.