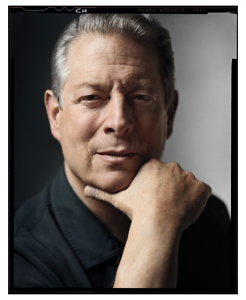

A Life’s Work to Save the Planet

Despite climate calamities unfolding daily around the globe, Al Gore finds hope for the future

The climate-change debate is one of the most enervating and dispiriting in American life, with scientists and activists pushing hard to switch course on fossil fuels while lawmakers and other citizens dig in their heels, resistant. No public figure has been so identified with climate change as former Tennessee Senator and U.S. Vice-President Al Gore, who first tackled the contentious topic back in 1992 in his bestselling book, Earth in the Balance, and then achieved a kind of superstardom in 2006 with the Oscar-winning documentary, An Inconvenient Truth. An associated book also topped bestseller lists.

Last summer Gore and his colleagues brought out another film: An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power; Rodale has again published the book tie-in. Although it hasn’t attracted nearly the box-office business as its predecessor, An Inconvenient Sequel unpacks the latest scientific data and spotlights ongoing advocacy efforts around the world. Gore focuses on three simple questions: “Must we change?” “Can we change?” “Will we change?” He answers the first two with a resounding “yes” but is more ambivalent about the third.

Last summer Gore and his colleagues brought out another film: An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power; Rodale has again published the book tie-in. Although it hasn’t attracted nearly the box-office business as its predecessor, An Inconvenient Sequel unpacks the latest scientific data and spotlights ongoing advocacy efforts around the world. Gore focuses on three simple questions: “Must we change?” “Can we change?” “Will we change?” He answers the first two with a resounding “yes” but is more ambivalent about the third.

First, the bad news: in the decade since the release of An Inconvenient Truth, our planet has continued to heat up, shattering records, especially in the Middle East. Ocean temperatures have also mounted, killing off fish populations and churning out more potent cyclones. Rainfall patterns have shifted, trailing snails and mosquitoes and other carriers of viruses, such as Zika. The delicate chains of microbial life, which have evolved over hundreds of millions of years, are mutating in ways that could threaten us all. Historical droughts have turned Western forests to dry kindling, spawning raging fires. Deserts are spreading.

Indeed, An Inconvenient Sequel paints a dire portrait of a world spinning into its own hellscape. But, surprisingly, Gore chimes a note of optimism: “In just the past 10 years the cost of clean, renewable solar energy and wind energy has fallen so quickly that in a growing number of regions throughout the world, it is now cheaper than electricity made from the burning of fossil fuels—and the cost continues to decline year by year.”

Gore credits technology with nudging us back from the brink of apocalypse. “Some areas,” he says, “such as computer chips, flat screen televisions, and mobile telephones, respond to research and development spending in an almost magical manner. Not only does the cost go down much faster than anyone expected, the quality goes up at the same time.” A decade ago we didn’t know that the curve of energy costs would dip precipitously, allowing the invisible hand of the market to propel us forward even as Washington lagged.

The book’s text recedes following Gore’s introduction, morphing into a lavish collage of charts and photographs and stylish topography. Gore calls it “an action handbook,” but while there are prescriptive policies here—solutions, or at least ideas for solutions—much of the book seems designed primarily for coffee-table display.

The book’s text recedes following Gore’s introduction, morphing into a lavish collage of charts and photographs and stylish topography. Gore calls it “an action handbook,” but while there are prescriptive policies here—solutions, or at least ideas for solutions—much of the book seems designed primarily for coffee-table display.

The most engaging feature of An Inconvenient Sequel is the miniature profiles embedded throughout the book. A young Filipino whose city was flattened by Typhoon Haiyan commits to studying the effects of climate change on oceans. An African-American woman from Alabama founds a nonprofit devoted to cleaner water, better health, and rural enterprise. A wealthy Chinese real-estate developer integrates sustainable construction into his projects. An Indonesian immigrant invokes verses in the Qu’ran to convince her San Diego mosque to celebrate “a Green Ramadan”—and her Imam installs solar panels on the roof.

In the end, these inspiring, intimate stories carry more weight than any single politician’s call to arms. We should all feel a debt of gratitude to Al Gore for his life’s work—and to a new generation of activists for cultivating and expanding the ground he’s seeded, from continent to continent.

Hamilton Cain is the author of This Boy’s Faith: Notes from a Southern Baptist Upbringing and a finalist for a 2006 National Magazine Award. A native of Chattanooga, he lives with his family in Brooklyn, New York.

Hamilton Cain is the author of This Boy’s Faith: Notes from a Southern Baptist Upbringing and a finalist for a 2006 National Magazine Award. A native of Chattanooga, he lives with his family in Brooklyn, New York.