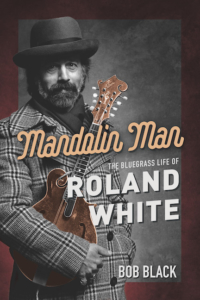

A Man and His Mandolin

Bluegrass legend Roland White always put the music first

In Mandolin Man: The Bluegrass Life of Roland White, author and banjo player Bob Black gives us a book about a musician in which the music rings out — and is never drowned out.

That’s because White seems to have been one of those rare legends who always put the music first, who treated his fellow musicians (including young ones in need of a mentor) with respect, and never cared much for fame or fortune.

“He lived to play the music,” Black writes. “It was his passion. Recognition didn’t matter; his ego could handle that.”

But make no mistake, White was a legend — a player of uncommon ability and feel who embraced traditional bluegrass, with Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys and Lester Flatt’s Nashville Grass, and also took the music to new and adventurous places with the Kentucky Colonels, Country Gazette, the Nashville Bluegrass Band, and his own band. He was beloved, especially by those he befriended at the beginning of their careers, like Marty Stuart and Jim Lauderdale. He was profoundly influential, even if the average music fan didn’t know his name.

Consider: When White died April 1 at age 83, The New York Times’ 1,100-word obituary lauded him as “a mandolin player and singer who helped shape major developments in bluegrass and country-rock over a seven-decade career.”

Credit Black, a former member of Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys who also has performed with Ricky Skaggs and Ralph Stanley, for recognizing White as worthy of a full-length biography. He’s done a thorough job of capturing this song-filled life.

Credit Black, a former member of Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys who also has performed with Ricky Skaggs and Ralph Stanley, for recognizing White as worthy of a full-length biography. He’s done a thorough job of capturing this song-filled life.

If you’re weary of music bios where the art gets lost amid the egos, feuds, drugs, and other fame trappings, this one’s for you. Roland White’s your man.

At 6, he was attempting to play chords on the family guitar, accompanying his fiddle-playing father, Eric. Young Roland also tried the fiddle — it “squeaked and squawked,” Black tells us, but his father encouraged him to keep trying. Then, one day his dad showed up with a new instrument:

Roland asked his dad, “How did you learn to play it so fast?”

“Well, it’s tuned like my fiddle,” replied his dad. “It has frets and you play it with a guitar pick.” He played another tune, and then he said, “Here, it’s yours,” handing the mandolin to Roland before walking away.

At 8, White was helping his mother, Mildred, in the kitchen, listening to country music on the radio and telling her that’s what he wanted to do someday — sing on the radio. Just as his dad encouraged him through that youthful squeaking and squawking, so did his mom. Practice hard, she told her son, and you’ll get there.

Those early scenes — portraits of the picker as a young tyke — show how determined White was, already, to achieve his dream. A family band formed, playing for free at Grange Hall functions and other gatherings. “Before long,” Black writes, “Roland started insisting on having band rehearsals every day.”

A child’s dreams can be as fleeting as they are frivolous. But not White’s. By 16, with the family having moved from Maine to California, he was playing in a band called Three Little Country Boys with his brothers Clarence and Eric Jr. He had also joined the musician’s union — and opened a savings account at the Bank of America. There were band outfits to buy and travel expenses, after all.

It wasn’t long before Roland and his brothers met Bill Monroe, who was touring the West Coast, and invited him home for dinner. More visits followed; Monroe especially like the banana bread for dessert, we’re told. And after dinner came the real main course — they played music.

Black chronicles it all with care and detail, as the kid with the dream, and the drive to make it happen, developed the chops to join his heroes in the professional ranks. What a career White had — from playing in the Kentucky Colonels with brother Clarence (a guitar icon and future member of the Byrds who would die at 29, struck by a drunken driver), to serving as a sideman first for Monroe (on guitar) and then Flatt, to making his own music with solo albums like the much-loved I Wasn’t Born to Rock’n Roll.

Black does a nice job of explaining White’s musicianship in ways non-musicians can understand:

There are countless mandolin players who can play swarms of notes guaranteed to blow the listener away. It’s sometimes said of these types of musicians: “I wish I could do that, and then not do it.” But Roland is different. He’s been around long enough to differentiate between musical bluster and the real thing. He’s grown up with an instrument in his hands. It’s a part of him.

It’s a shame White didn’t live to see the publication of this fine biography. But it wasn’t acclaim he was ever after. It was always about the music, from that day in the kitchen with his mom, listening to the radio and daring to dream, to playing stages all around the world.

You may not know the name. But as a musician, a mentor to others, and a role model for anyone who dreams of playing professionally, Roland White played second fiddle — or mandolin, as it were — to no one.

David Wesley Williams is the author of the novel Long Gone Daddies (2013) and the forthcoming Everybody Knows (JackLeg Press, January 2023). His short fiction has appeared in Oxford American, Kenyon Review Online, and in Akashic Books’ Memphis Noir. He lives in Memphis.