A Masterful, Lyrical Satire

Memphis takes center stage in Richard Bausch’s Playhouse

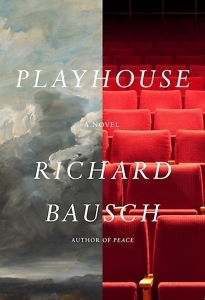

In Richard Bausch’s latest novel, Playhouse, a Memphis theater company stages a performance of King Lear to celebrate a high-profile relaunch. As rehearsals begin, celebrities sign on, and with the revitalized Globe Theater positioned as a beacon of cultured Memphis, the characters struggle to find harmony, let alone pull off the play.

A masterful, lyrical satire, Playhouse tells the story of the ensemble through the lens of three primary characters. Thaddeus Deerforth, general manager of the Shakespeare Theater of Memphis, must keep the production on track, the egos in check, and sort out a marriage akin to “two strangers in an airport.” Longtime company actor, Claudette Bradley, is determined to care for her elderly father, while keeping distance from her troubled ex-husband. Local celebrity Malcolm Ruark hopes his performance in Lear will blot out a well-publicized scandal.

The company is graced by a high-profile visiting director, whose self-indulgent adaptation is matched by his salacious sexual advances. With the casting of a Netflix star, the production soon churns like the Mississippi River current.

In many ways, Playhouse is a send-up of culture-making itself. To Thaddeus and his crew, the looming deadline is as grave as a terminal disease. Off stage, they must kowtow to the peculiar set of donors who control the Shakespeare Theater’s fate. And then there are those pre-existing complications, such as the headlines that dog Ruark over a bust for drunk driving … with his alluring, underaged niece in the car. Shadowing all is the allegiance to Lear and how to stay faithful to the text.

Playhouse showcases both poetic description and double-edged dialogue. Any given paragraph can provoke a sigh, then a snort. In one scene, when theater members gather at a rooftop bar, they notice the “gathering dark roil of cloud…as if the whole sky was staggering towards them…laced with lightning.” (This storm is one of the many nods to Lear.) In another, when Claudette’s unstable ex-husband is denied the leading role, he tries to save face by brushing things off: “Well, anyway, I’m in the late stages of a breakdown. So I don’t think I’m available.”

Playhouse showcases both poetic description and double-edged dialogue. Any given paragraph can provoke a sigh, then a snort. In one scene, when theater members gather at a rooftop bar, they notice the “gathering dark roil of cloud…as if the whole sky was staggering towards them…laced with lightning.” (This storm is one of the many nods to Lear.) In another, when Claudette’s unstable ex-husband is denied the leading role, he tries to save face by brushing things off: “Well, anyway, I’m in the late stages of a breakdown. So I don’t think I’m available.”

The city of Memphis — one social slice of it, anyway — is a stage all its own. Bausch marks it well enough, from Summer to Gayoso Avenues, to dry rub ribs from The Rendezvous. The geography serves to parody the arts and arts-funding set, as defined by Southern social codes and genteel benevolence. There are the “Cosmetics Tycoons” who fund the Globe and its players and the insiders-with-an-asterisk, such as the “young lady who becomes a Memphis society girl growing up in Butler, Arkansas.” The chichi wines listed throughout this novel will escort you straight out of your league.

Playhouse requires a commitment, given the number of folks on the page. Readers may find it necessary to turn time and again to the playbill-style Cast of Characters at the beginning of the book. What’s more, some scenes are overgrown, like shoots around a blossom. Yet the narratives come clear as the story moves on. The final section is built on shorter vignettes, accelerating toward opening day — and the unseen turn that will upend everything.

Bausch’s 21 published novels and story collections have earned a trophy case of prizes, confirming his status as a literary master. He’s also noted for his repertoire of jokes and one-liners, many of which perk the novel. (“What do you call an actor with two brain cells?” “Pregnant.”)

Unlike Lear, this story isn’t about British royalty, murderous family, or a continental power struggle. It’s about a secondary market theater director whose anxiety threatens his beliefs. About the anguished attempt to grow away from a dying marriage, confused by the process, “wanting not to say the wrong thing or do the wrong thing.” It’s about the precocious 18-year-old who trades on both looks and talent and the failed actor who dreams of a return to the life that was.

As such, this is domestic tension at its finest. Given the breadth of humanity, the poeticism and wit, Playhouse delivers the ultimate understatement: “It is all so terribly normal. It’s ridiculous.”

Odie Lindsey is the author of the story collection We Come to Our Senses and the novel Some Go Home, both from W.W. Norton. He is writer-in-residence at the Center for Medicine, Health, and Society at Vanderbilt University.