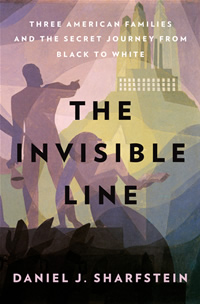

A Matter of Black and White?

Daniel J. Sharfstein argues that America’s color line isn’t as straight as we might think

For years racial identity in America was defined by strict laws and social mores. Such dicta told people whom they could marry, how they could do business, and, for the first century of the nation’s existence, who owned whom. But no matter how rigid things looked on paper, on the ground it was a different story. In The Invisible Line, Daniel Sharfstein, an associate professor of law at Vanderbilt University, follows three families from the Civil War to the civil-rights era, showing how each managed to manipulate racial restrictions and live and thrive in the very communities that might have shut them out.

This is not a book about black people who deliberately sought to pass as white. “Racial migration,” says Sharfstein, “was not just the province of the small group of people of African descent who could make the physical claim to be white. It touched the lives of men and women and entire communities who made every effort to epitomize what black and white were supposed to be.”

Sharfstein’s subjects are three African-American families who, despite coming from widely differing circumstances, experienced a color line that was far more permeable than most history books would have us believe. The Gibsons were successful sugar planters and horse breeders who split their time between Louisiana and Kentucky. They were also slaveholders, unaware that their patriarch had been a free man of color. The Walls were descended from a black family that had once fought hard for the rights of citizenship. By the turn of the century, however, they were living as white in Washington, D.C. As farmers on the harsh Kentucky frontier, the Spencers’ value as neighbors silenced any questions about their dark skin. The integration of these families required the cooperation of neighbors and business associates who chose to accept them as equals in spite of rumors about their race. In other words, Sharfstein’s subjects were able to defy legal and social restrictions on race without denying their own friends, relatives and neighbors.

Sharfstein’s subjects are three African-American families who, despite coming from widely differing circumstances, experienced a color line that was far more permeable than most history books would have us believe. The Gibsons were successful sugar planters and horse breeders who split their time between Louisiana and Kentucky. They were also slaveholders, unaware that their patriarch had been a free man of color. The Walls were descended from a black family that had once fought hard for the rights of citizenship. By the turn of the century, however, they were living as white in Washington, D.C. As farmers on the harsh Kentucky frontier, the Spencers’ value as neighbors silenced any questions about their dark skin. The integration of these families required the cooperation of neighbors and business associates who chose to accept them as equals in spite of rumors about their race. In other words, Sharfstein’s subjects were able to defy legal and social restrictions on race without denying their own friends, relatives and neighbors.

The Invisible Line is based on primary source material, which Sharfstein weaves into chapter-length narratives. Each chapter recreates a significant event in a family member’s life and is titled according to family, place, and date. The stories range from personal anecdotes to political conflicts and courtroom dramas. They portray race in post-colonial America as a complex matter in which skin color often takes a back seat to more practical realities.

“Spencer: Jordan Gap, Johnson County, Kentucky, 1855,” for example, tells the story of Jordan Spencer and his family. Spencer was a hard-working landowner with an unusual appearance—census takers labeled him “mulatto.” The fact that he dyed his hair red fooled no one but did signal to his neighbors that, for Spencer, race was a private matter. In Spencer’s time, even slavery’s opponents sometimes relied on a policy of difference. They supported abolition not because blacks were equal to whites, but because slaveholding jeopardized the owner’s soul and polluted a cheap labor market. Spencer, however, was a farmer-businessman who lived his life in debt. That indebtedness bound him to his community. “With every cabin raised, every child born, and every ear shucked, it made less sense to ask whether the Spencers were different,” says Sharfstein. The community chose to ignore questions about Spencer’s genealogy because it was invested in him.

Similarly, “Gibson: Mars Bluff, South Carolina, 1768” tells the story of Gideon Gibson, the leader of a group of backcountry farmers called the “Regulators,” whose mission was to hold their English governors accountable for promised legal reforms. A free man of color, Gibson owned slaves. He had a penchant for violence and thus was seen by the authorities as a particular threat, so the local militia was charged with hunting him down. But Gibson was a wily adversary. He fought off attempts at capture, eventually winning the reforms his Regulators sought.

Similarly, “Gibson: Mars Bluff, South Carolina, 1768” tells the story of Gideon Gibson, the leader of a group of backcountry farmers called the “Regulators,” whose mission was to hold their English governors accountable for promised legal reforms. A free man of color, Gibson owned slaves. He had a penchant for violence and thus was seen by the authorities as a particular threat, so the local militia was charged with hunting him down. But Gibson was a wily adversary. He fought off attempts at capture, eventually winning the reforms his Regulators sought.

Because the Gibsons were successful in business, Sharfstein argues, the authorities in Charleston were unwilling to confront him on racial grounds. Ironically, the racial system that threatened both Gideon Gibson and Jordan Spencer ended up being their salvation. “The Gibsons were hardly the only family who were fashioning new identities for themselves,” says Sharfstein. “If the colony drew the color line too strictly, large numbers of established whites might be vulnerable to or otherwise touched by reclassification.”

The Invisible Line revels in this kind of irony. For every advancement and setback in America’s struggle with questions of race, there’s a universe of unintended consequences, and this dynamic makes for great storytelling. The Invisible Line reads like a collection of short fiction in which Sharfstein never succumbs to clichéd endings or oversimplified character arcs. The Gibsons, the Walls, and the Spencers are real people who were operating during complicated times, and such stories, when told by a writer with Sharfstein’s narrative skill, can be as compelling as any in the world of fiction. “Their histories reveal constant questioning, acts of interpretation and reinterpretation, stubborn assertions of will, and outright escape,” he writes. “More than anything, this is their legacy. They help us understand the rules of the past while insisting that we make our own.”

Daniel Sharfstein will discuss The Invisible Line at 7 p.m. on February 22 at Borders Books in Nashville.